Figure A. Wharton Esherick’s “Hammer Handle Chair”, not dated. Compare with Marcel Breuer’s “Slat Chair” pictured below to the right.

Although the many now famous pieces produced by the Bauhaus faculty and students, and the pieces that came out of Esherick’s Paoli studio differ greatly in their use of materials and approach to mass production (Esherick’s wholly one-of-a-kind, unique pieces compared to the Bauhaus’ embrace of mass production), their design techniques similarly focused on achieving a complex degree of utilitarianism and an overall aesthetic informed by the materials in which they worked. Opened in 1919 in Dessau, and ultimately moving to both Weimar and Berlin, the Bauhaus asserted a progressive curriculum focused on a modernist reinterpretation of the Arts and Crafts tradition. The school boasted such influential artists as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Josef Albers, Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, László Moholy-Nagy, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe as members of its faculty, until the Nazi Regime closed it in 1933 . Both Esherick and the Bauhaus sought the creation of an environment in which all the arts commingled, the distinctions between artistic mediums collapsed, and students could develop a new, democratic approach to the creative process that would revolutionize how society and the individual would interact with art.

Esherick played a key role in leading the first generation of an American modernist Arts and Crafts movement that was rooted in the earlier revivals of the European Arts and Crafts tradition happening in Germany, England, and France during the mid-19th century. In the turbulence of the Industrial Revolution, which reorganized every aspect of an antiquated European society that still functioned on ancient economic and manufacturing practices, some artists refused to sacrifice the incomparable quality of a handmade object for the efficiency of a machine-made product; particularly English Arts and Crafts movement founders John Ruskin and William Morris. Ruskin and Morris developed the artistic philosophy of working with natural materials, paying close attention to unique aesthetic details for each piece, and retaining the knowledge of master craftsmanship without the aid of new technologies. By time the 1920s rolled around, and Esherick and the Bauhaus had begun their work, the prior had adapted his principles to embrace possibilities allowed by stocking a modern workshop, and the latter had modified its vision as a means to retaining craftsmanship in modern industrial society. Still, both kept the original Arts and Crafts ideology at the core of their styles, with Walter Gropius, the first director of the Bauhaus, even citing Ruskin and Morris as primary influences in the establishment of the school.

Figure C. Wharton Esherick, Bok House Spiral Staircase, 1938. Compare with the Bauhaus Foyer, below to the right.

Also shown: The Actress, 1938, center of photo.

Gropius’ 1919 “Bauhaus Manifesto and Program” begins with the line: “The ultimate aim of all visual arts is the complete building!” This sentiment emphasizes the school’s interest in the German concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, roughly translated as the “total work of art,” in which every aspects of a structure, from its walls to its decorations and furniture requires the insight of artistic craftsmanship. As far as an American reinterpretation of this concept, perhaps no building succeeds in achieving that aim as well as Esherick’s studio, in which the artist’s hand has left its mark on every detail. From the sloping external lines of the studio’s structure to the autumnal fresco on the 1966 addition, the individually painted window frames to the purple stained pine floors of the 1926 portion of the studio and the handcrafted furniture and sculpture that inhabits the building, Esherick created a truly organic structure atop Valley Forge Mountain that would have satisfied Gropius’ call for the ultimate visual art. Beyond their shared interest in Gesamtkunstwerk, many parallels exist within their artistic philosophies as well.

When asked by a woodworking class for advice from the master when visiting his studio, Esherick infamously said to “ditch your teacher”, an idea Gropius also shared and expressed in the manifesto, writing: “Art… in itself it cannot be taught.” Both viewed the workshop as the optimal environment in which to gain experience and hone the artistic craft: Gropius hoped that the Bauhaus workshop would absorb any kind of classroom space and Esherick learned his craft skills within his workshop and the carpentry studio of his friend and neighbor John Schmidt. In their minds, art and craftsmanship required the use of one’s hands and materials, informed by skills that no textbook had the ability to impart.

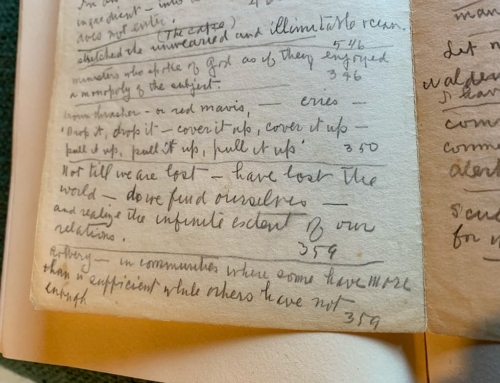

When viewing the relationship between Esherick and the Bauhaus, one can imagine a spectrum displaying the modernist interpretations of the 19th century Arts and Crafts revival, with Esherick at one end favoring local, natural materials and the Bauhaus at the other, applying craft technique to innovative technologies and materials. Both ultimately achieve similar degrees of utilitarianism with compositions emphasizing ingeniously functional forms that are fluid, curvilinear and highly aesthetic. Although the Bauhaus usually favored new materials such as steel and iron, an early piece by architect and furniture designer Marcel Breuer, the 1922 Slat Chair, uses unmodified prefabricated wood slats in a minimalistic design to achieve a wholly functional chair, extremely similar in conception to Esherick’s famous Hammer Handle Chair (see Figures A and B). Furthermore, the similarities in design between Esherick’s spiral staircase for the Curtis Bok House and the spiral staircase in the foyer of the Weimar Bauhaus, both with floating stairs appearing to cantilever out from the wall display vivid artist camaraderie (See figures C and D). More than anything, the early modernists attempted to define and defy the boundaries of each artistic medium in order to create a higher degree of total art, and in the first half of the 20th century, no institute developed a more successful process to achieve that than the Bauhaus, and no artist succeeded more in manifesting that vision than Wharton Esherick.

Post written by WEM volunteer Mike Cavuto.