Wharton Esherick’s work was well-traveled in his day. Selections of the artist’s work often went to New York venues like the Whitney, Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, crossed the country to San Francisco for the Golden Gate Expo, and even hopped across the pond for an International Sculpture Competition in London and the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. After his death, Esherick’s work continued to travel, finding permanent homes in museums across the country and over the Atlantic. When we think about an object’s itinerary, the finished piece is only one part of the story.

Wharton Esherick, First Born, 1927. Brazilian rosewood, padauk, and snakewood.

Wharton Esherick, First Born, 1927. Brazilian rosewood, padauk, and snakewood.

What if we step back in time to think about the travels of Esherick’s materials before he transformed them into the objects we know and love today? Some materials came to the Paoli studio from far-flung places. What can we learn about Esherick’s work when we consider the travels of his raw materials, especially the tropical hardwoods that came to the Paoli hillside already full of stories from their travels? How did they come to arrive at Esherick’s studio on a quiet Pennsylvania hillside?

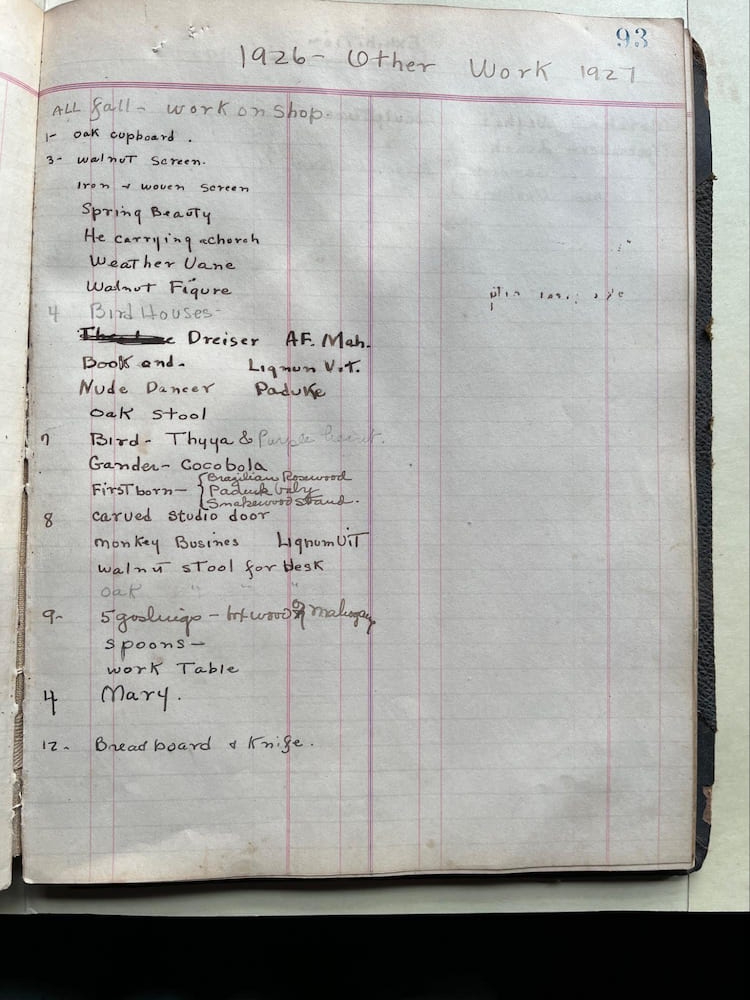

Wharton Esherick worked with a wide variety of tropical hardwoods early in his career. A ledger book that Letty Esherick created to document her husband’s work reads like a catalog of tropical hardwood species: African mahogany, lignum vitae, padauk, Brazilian rosewood, purpleheart, snakewood, cocobolo, and thuyya, among others. The majority of this valuable material came from places where the tropical hardwood trade has roots going back centuries. Esherick transformed these raw materials into sculptures like The Centaur, First Born, and Cat in the Grass. These woods occasionally became components for furniture, like a carved desk for Letty from 1926 that incorporates an ebony latch.

Wharton Esherick’s ledger book, 1920-1931.

Wharton Esherick’s ledger book, 1920-1931.

These pieces of furniture and sculpture were all made during the 1920s, Esherick’s first decade working in wood. Ed Ray, the local lumber supplier Esherick began working with in the mid-1930s, recalled that “in the early years…[Esherick] used the exotic imported woods… for the first 10 years he worked in these exotic woods. And then he got into bigger pieces of furniture and sculpture… And he couldn’t get a big log of these exotics, a crotch of cocabolla— so he turned to local woods.” It’s possible that Esherick sourced some of his tropical hardwood from his collaborator John Schmidt, a local German-trained cabinetmaker who was known to use “an awful lot of mahogany,” according to Ray.

Some of Esherick’s most celebrated pieces such as his music stand, library ladder, and captain’s chairs are made from local hardwoods like cherry, walnut, and oak. However, he returned to tropical hardwoods on occasion for commissions depending on the tastes and proclivities of his clients. For example, the bedroom suite Esherick made for his friend Marjorie Content’s New York apartment in 1932 uses a significant amount of padauk wood for the show surfaces, and unifies the daybed, vanity, and dresser.

Photograph of Marjorie Content’s bedroom set, 1933. Photo by Marjorie Content.

Photograph of Marjorie Content’s bedroom set, 1933. Photo by Marjorie Content.

Padauk trees grow in regions such as Central and West Africa, South and Southeast Asia, as well as many parts of the South Pacific. Its commercial use in furniture making dates back to the British occupation of Burma in the early 19th century. Like padauk, many types of tropical hardwoods played key roles in imperial economies and the trade of luxury goods.

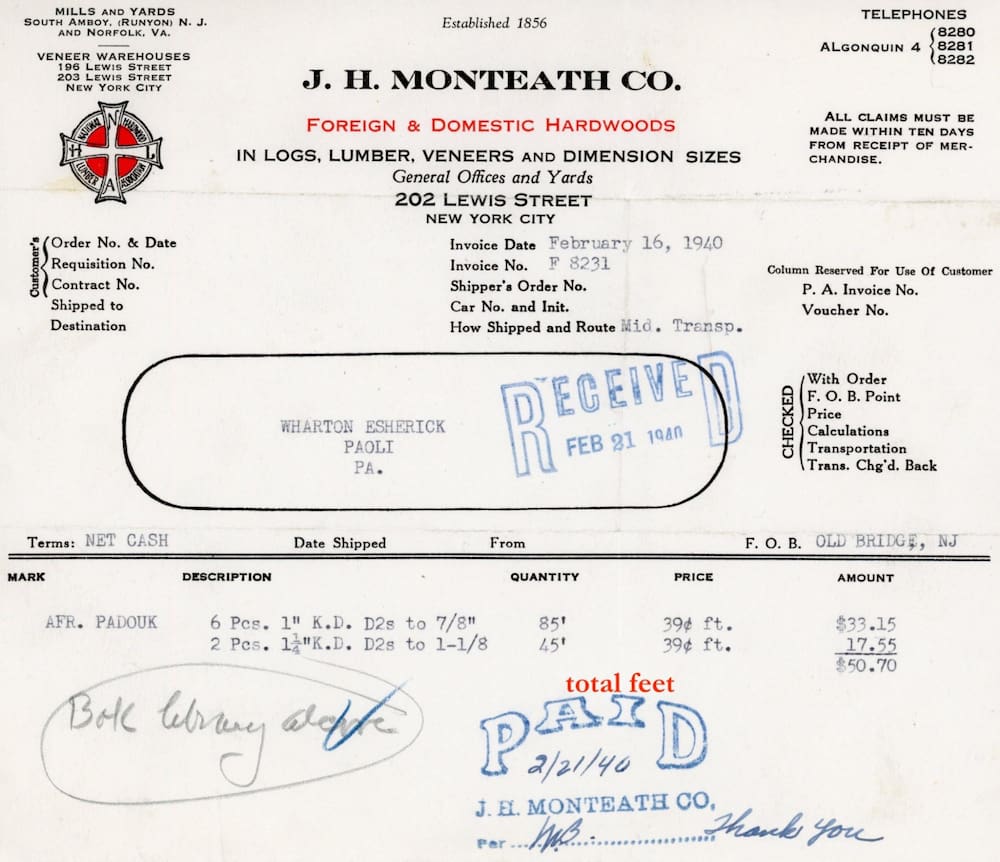

Archival documents related to Esherick’s largest commission, the home of Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Curtis Bok that began in 1935, give us a glimpse into where the artist sourced his tropical hardwood. The order forms and correspondence from the tropical hardwood dealer J.H. Monteath and Company in our archives draw a line to the padauk library alcove in the Bok house. The bills and piece of correspondence help us determine that the padauk came from Africa, was shipped to a port in New Jersey, and that the lumber was of the best grade and “dressed” on both sides at Monteath’s lumberyard. Correspondence from January 1940 suggests that Esherick must have had a relatively close relationship with people at Monteath, since the letter is addressed “My dear Mr. Eherick” [sic], and opens “it was nice to hear from you again after an absence of over a year.”

Monteath has been importing lumber since the middle of the 19th century. Historically, they supplied wood for activities like shipbuilding, hardwoods and veneers for fine furniture and instruments, lumber for construction, and heavy-duty timber for engineering and architectural work. By the time Esherick was known to be purchasing from them, Monteath was supplying other craftspeople and designers such as Chaim Gross, Alexander Calder, and Marcel Breuer. They often advertised in publications like Craft Horizons and later in Fine Woodworking, which tells us Monteath knew where to find their audience. At this time, their biggest business was importing Brazilian Rosewood, a popular material for furniture makers throughout the country.

Invoice from J.H. Monteath for African padauk used in Curtis Bok’s library alcove, 1940

Invoice from J.H. Monteath for African padauk used in Curtis Bok’s library alcove, 1940

What the materials between Esherick and Monteath don’t detail for us is how the padauk made its way from Africa to the importer’s yard in South Amboy, New Jersey. Who was involved in harvesting the wood, involved in business with the American lumber importer, and getting it to port before it crossed the Atlantic?

Tropical hardwood made its way from its native habitat to Monteath’s lumberyard in several ways. Sometimes for important clients, the company president Monteath Dayton would travel overseas to personally select trees for felling to help ensure quality control. For example, Dayton traveled to present-day Myanmar in 1935 to personally select teak trees for the Navy. He even took the long journey by airplane, rail, and car to reach forests in Brazil where rosewood grew at an altitude of 1,500 feet. Dayton had to work with half a dozen different shippers to send the 3,000 tons of timber that were felled down from this mountainous region to North America. The importers had their materials shipped by boat as whole logs of timber and would mill and dry them once they were in the New Jersey lumber yard.

Another way Monteath acquired their lumber was through third-party brokers who had working relationships with shippers abroad. For instance, when the company moved from Canal Street to Park Avenue in 1946, Monteath Dayton’s brother George wanted a new mahogany desk. Dayton had to buy a whole bundle of lumber that was sent on consignment to the third-party salesperson from a shipper on the Gold Coast just to acquire the few pieces of mahogany he wanted.

Still from Industry on Parade film showing J.H. Monteath’s lumberyard with a log of Lignum Vitae and patron sculptor, 1952.

Still from Industry on Parade film showing J.H. Monteath’s lumberyard with a log of Lignum Vitae and patron sculptor, 1952.

Image source: Periscope Film, Industry on Parade, 1952. Accessed via: https://archive.org/details/12764industryonparadebringingoutthebrimestonevwr

What is not included in this are the stories of the skilled and knowledgeable labor force that was involved in locating and felling trees, and transporting the timber down mountains, rivers, and roads to port. The workers involved in extracting timber were often involved in a dangerous and exploitative business. Their work likely entailed leveraging their knowledge of native trees, landscapes, and transportation routes to retain power in the face of this dangerous and exploitative labor. The success of the timber trade undoubtedly relied on this type of knowledge. While these workers’ stories may be buried deep in an archive or left out altogether, the Gold Coast shipper from whom George Dayton acquired his lumber may help to illustrate the ways indigenous people involved in the timber trade leveraged their knowledge as a form of power.

George Grant was a wealthy timber merchant in Ghana. Grant played a pivotal role both in establishing a movement for Ghana’s independence from Britain known as the United Gold Coast Convention, and in forming the country’s first self-determining government with Kwame Nkrumah. Grant was born into a wealthy merchant family, which came in handy as he developed lucrative business contacts in the UK and US in the early twentieth century for his firm George Grant and Company. By 1920, Grant owned a ship that transported goods between ports. When Grant consigned the mahogany logs that ended up in the possession of Monteath in the 1940s, he had offices open in London, Liverpool, and Hamburg, and expanded his shipping operations throughout Ghana. Records suggest that Grant employed upwards of a dozen Europeans for his business, and likely employed indigenous Ghanaians as well. At the time, Grant was breaking into a trade dominated by European and American firms.

Executive members of the United Gold Coast Convention, Ghana’s first political party for independence, 1947.

Executive members of the United Gold Coast Convention, Ghana’s first political party for independence, 1947.

Image source: Deo Gratias Studios, 1947.

George Grant’s transition from timber magnate to early political leader fighting for an independent Ghana may help to illuminate the type of negotiations other indigenous people who are left out of the historical record took part in as they worked with Western timber importers. For his part, Grant used the connections and finances he amassed from his timber business to protect the commercial and labor interests of his fellow Ghanaians who lived and worked under exploitative colonial rule. Grant’s funds also allowed him to be the principal financier of an independence movement and associated political party that he helped establish in the 1940s. In short, Grant used his power and resources to empower and protect people most at risk. Those who worked in dangerous labor conditions felling trees may not have had the opportunity to leave their mark on the historical record in the same way someone like George Grant could. However, they too had to leverage their power: knowledge of landscapes, native trees, travel routes, and the like to protect their interests as best they could.

Hoisting timber outside 1926 Studio, undated.

Hoisting timber outside 1926 Studio, undated.

When we dig into the itinerary of Wharton’s hardwoods, it becomes clear that wood can be political! Between the different roles tropical hardwood played for imperial governments and a subversive figure like George Grant, the trade was deeply embedded in global social and political climates. Even during the Cold War, hardwood like Circassian Walnut became a complicated resource that was the subject of strategic embargoes. Upon their arrival to the Paoli hillside, tropical woods allowed Esherick to experiment with and express himself through different types of materials. However, the story of these materials begins well before reaching Esherick’s studio, and they arrive already laden with accounts from their travels. To each person who encountered them from the time they were logged to the time they arrived at the artist’s studio, these woods meant something different. Sometimes a cherished natural wonder, a livelihood, a vehicle for political or economic action, and sometimes a medium for artistic expression, the various things this wood meant to different people are carried with it whether we’re aware of them or not.

Post written by Ethan Snyder, Public Programs & Collections Manager

April 2024