March 2, 2024 – June 2, 2024

This year, at the Wharton Esherick Museum (WEM), we are celebrating the creative energy that Wharton Esherick found in the rhythms of life. Throughout 2024, our programs, exhibitions, and events will focus on art as it interacts with the rhythmic aspects of the natural world, inclusive of the human body. Shifting seasons, daily rituals, life cycles, and body mechanics are rhythmic movements that informed Esherick’s work, as they do for contemporary makers today.

Throughout Esherick’s hand crafted Studio, his sense of rhythm rings clear. From the intuitive axe strokes that define his wood sculptures, to the organic patterning of the stonework on the building exterior, he hewed to the tempo of breath and the cadence of landscape. In his desire to make nature his ultimate timekeeper, Esherick pushed against currents of industrialization in the machine-age era when he lived. Movement is Life, our spring exhibition, kicks off a year of programming at WEM that traces the thread of rhythms from the 1920s through the present.

This installation will be on view in our Visitor Center, which is open during our current tour hours. Please note, guests wishing to enter the Studio must make advance reservations for a tour.

Movement is Life explores modern dance as a context for the emergence of Wharton Esherick’s art. In the early 1920s, Esherick underwent an extraordinary transformation: he metamorphosed from an under-appreciated impressionist painter to a woodcarver whose dynamic modernist forms would carry him through an illustrious career. Esherick’s earliest woodworks—woodblock prints and decorative reliefs on frames and furniture—used swirling lines and rhythmic patterns to depict the natural world as alive. With his gouges, he rendered plants, animals, and human figures as pulsing with vital energies emanating from within them. Esherick struck this new direction at a time when he was involved with communities of women who practiced a form of modern dance called “rhythmics.” Broadly speaking, rhythmics was part of an early twentieth-century move toward using dance to revitalize world-worn bodies by reconnecting people with the rhythms of nature. Isadora Duncan, the most famous practitioner of this “natural dance,” gestured to the undulations of waves and breath, declaring “movement is life.”

The exhibition draws together a selection of woodblock prints, carvings, and archival photographs from the WEM collections, created during the five-year period, 1919-1924.

The purpose of the camp is for the development of Miss Doing’s system of rhythmics, which is designed to give a free, full, vigorous expression to the thought and feeling of people, who for the greater part of the year are subjected to the restraints and artificialities of city life. Not only those who wish to learn to dance come here, but many musicians, artists and writers who believe the power of expression in their chosen field to be greatly increased by what they learn from rhythmics.

Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics brochure, 1923

The purpose of the camp is for the development of Miss Doing’s system of rhythmics, which is designed to give a free, full, vigorous expression to the thought and feeling of people, who for the greater part of the year are subjected to the restraints and artificialities of city life. Not only those who wish to learn to dance come here, but many musicians, artists and writers who believe the power of expression in their chosen field to be greatly increased by what they learn from rhythmics.

Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics brochure, 1923

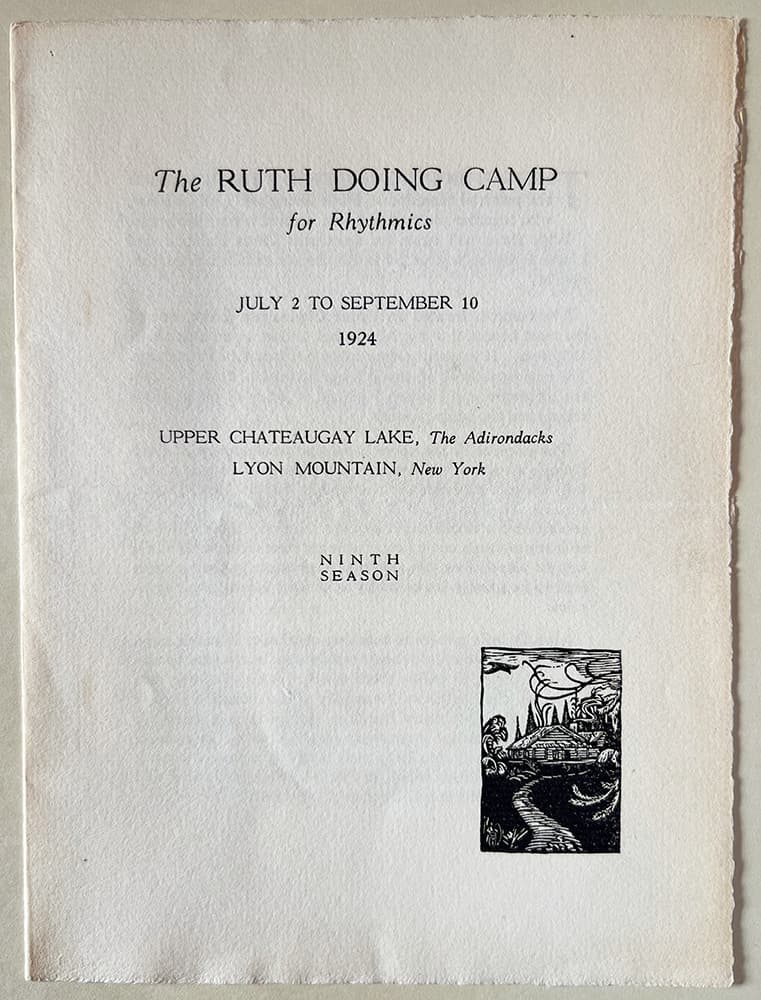

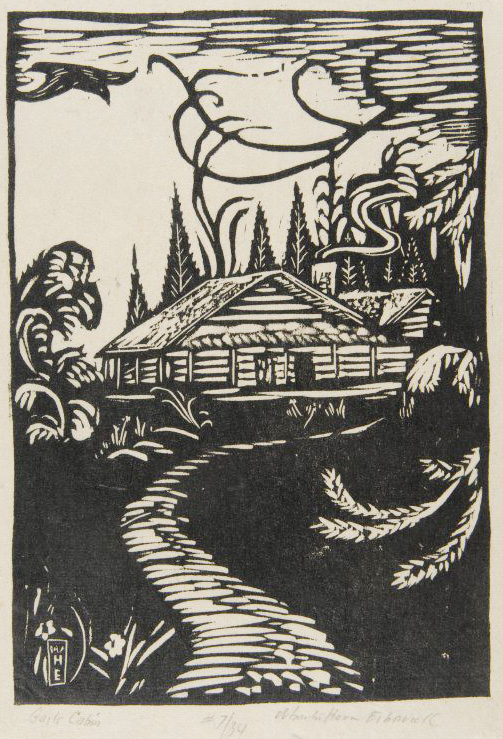

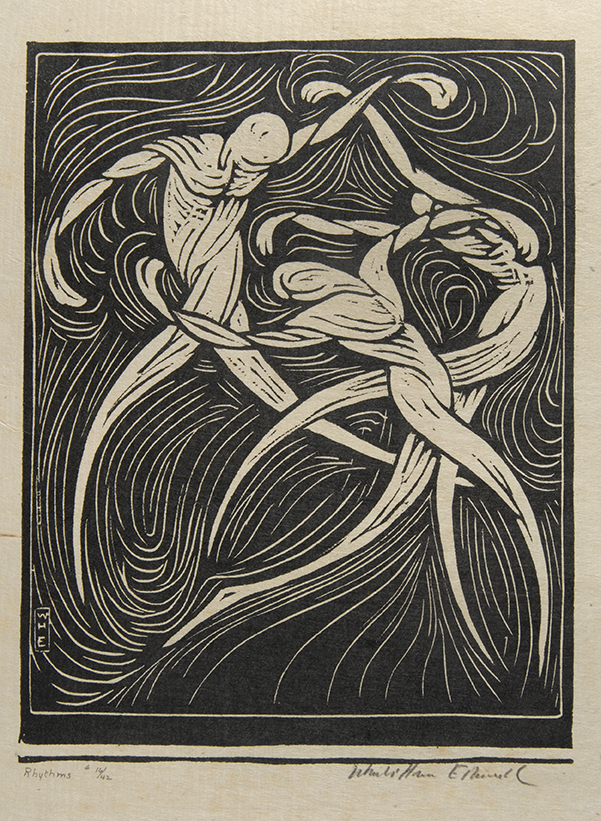

The cover illustration on each of these brochures is a reproduction of a woodblock print that Wharton Esherick created for the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics. The image at left is titled Rhythms, Opening, and at right, Gail’s Cabin. These illustrations were two of several commissions that Esherick completed for the dance camps as barter for his family’s camp fees.

In Rhythms, Opening, radiating lines impart a sense of vital energy that emanates from within the figures. In this way, the image supports the message of the brochure text, which describes rhythmics as invigorating activity to free the creative potential within people.

Study the movement of the earth, the movements of plants and trees, of animals, the movement of winds and waves—and then study the movements of a child. You will find that the movement of all natural things works within harmonious expression.

Isadora Duncan, “Movement is Life,” circa 1909

Study the movement of the earth, the movements of plants and trees, of animals, the movement of winds and waves—and then study the movements of a child. You will find that the movement of all natural things works within harmonious expression.

Isadora Duncan, “Movement is Life,” circa 1909

Rain, Wharton Esherick, circa 1919. Oil on canvas, wood, bronze. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Wharton Esherick painted Rain and carved its decorative frame in Fairhope, Alabama. He and his wife, Letty had traveled there from their home in Pennsylvania so that she could learn progressive teaching methods at The Marietta Johnson School of Organic Education. For Johnson, children were first and foremost developing organisms. Believing that book learning was not conducive to growth in the very young, she removed all of the desks in the classrooms of the lower grades. In place of books, Johnson instituted rich offerings in experiential learning. These included dance, which Letty taught, manual craft, and visual art, where Wharton was a part-time instructor.

It was in this environment that Wharton Esherick first set aside his paint brushes (he was then an aspiring painter working in the impressionist style) to try his hand at woodcarving. The carved wood frames that he created in Fairhope were the start of a long line of woodworks that he would fashion, including woodblock prints, decorative designs inscribed on antiques, wood sculptures, and—the works for which he is best known—sculptural furnishings of his design.

Carved Chest, anonymous cabinetmaker, Wharton Esherick woodcarver, 1923. Wood, Brass. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Carved Chest detail, anonymous cabinetmaker, Wharton Esherick woodcarver, 1923. Wood, Brass. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Photograph of stage set from Esherick family album, 1920. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Some of Wharton Esherick’s earliest endeavors in furniture making involved carving decorative reliefs on antique furniture. This chest, which the Esherick family used in their home, is one such work. Its carvings depict the land and buildings of “Sunnekrest,” the small farmstead where the Eshericks lived from 1913 until the mid-1930s. The front panel shows their house and the barn beside it. One of the most striking elements of the carving is its depiction of the Sunnekrest landscape, where swirling lines and abstract plant forms elicit unbounded biological exuberance.

A photograph from an Esherick family album reveals that a motif Esherick repeatedly in the chest carvings was also part of a stage set at the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics.

The way in which we were taught to move was of a piece: there was a sense of one movement flowing from another, often in a sequential way originating in the back. Many of the exercises were also based on deep spiral movements of the body.

Jane Dudley, student of Ruth Doing

The way in which we were taught to move was of a piece: there was a sense of one movement flowing from another, often in a sequential way originating in the back. Many of the exercises were also based on deep spiral movements of the body.

Jane Dudley, student of Ruth Doing

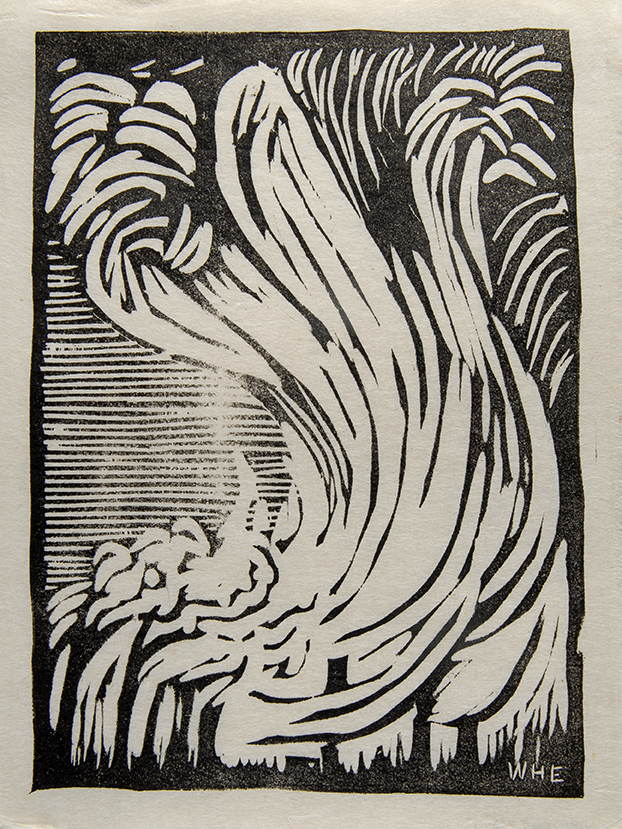

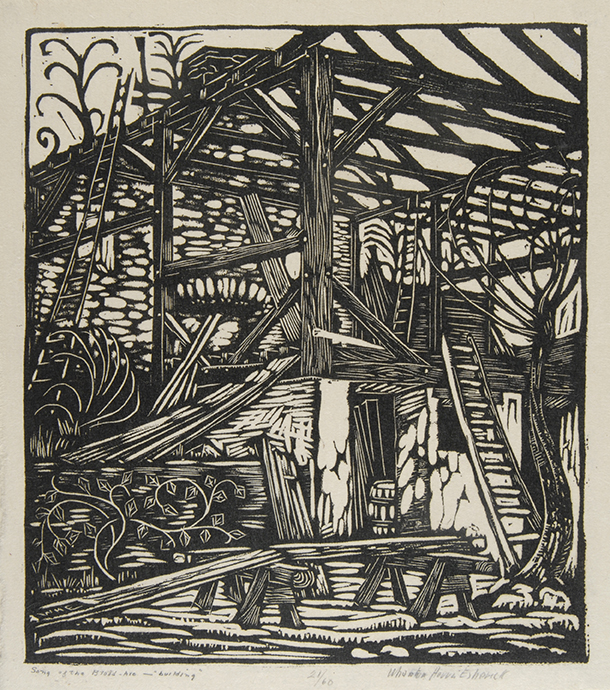

Gail’s Cabin, Wharton Esherick, 1923. Woodcut. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Photograph from an Esherick family album showing Gail Gardner (right) and Ruth Doing (center), with pianist Olga Mendoza (left), circa 1920. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

The title of the print Gail’s Cabin refers to Gail Gardner, an opera singer and life partner of dancer Ruth Doing. Gardner and Doing co-ran the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics, and the Gardner-Doing Camp for Rhythmics, as it was later renamed. Esherick’s rendition of Gardner’s cabin shows the picturesque quality of the setting and further–the flowing lines of curled tendrils and an undulating path create a sense of motion indicating a landscape that was not just scenic, but alive.

Building, Wharton Esherick, 1923. Woodcut. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Rhythms, Wharton Esherick, circa 1923. Woodcut. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

With woodcut illustration, Esherick found a venue for publishing his art. Building (left) is one of eighteen woodcuts that he created for a 1923 limited edition book: Song of the Broad-Axe, by Walt Whitman, published by the Centaur Press in Philadelphia. The text it illustrates, Whitman’s poem, “Song of the Broad-Axe” (1856), celebrates the physical work of building. There is an autobiographical component to Esherick’s woodcut in that the event it portrays is the remodeling of his barn, a building that is depicted in its finished state in the carvings of the chest below.

Rhythms (right) is one of several woodcuts by Wharton Esherick that were used to illustrate the publicity pamphlets for the Ruth Doing and Gardner-Doing dance camps. The highly abstracted group of figures in the print is an early instance of Esherick exploring the dynamism of the spiral motif, a form that animated many of his later sculptural works.

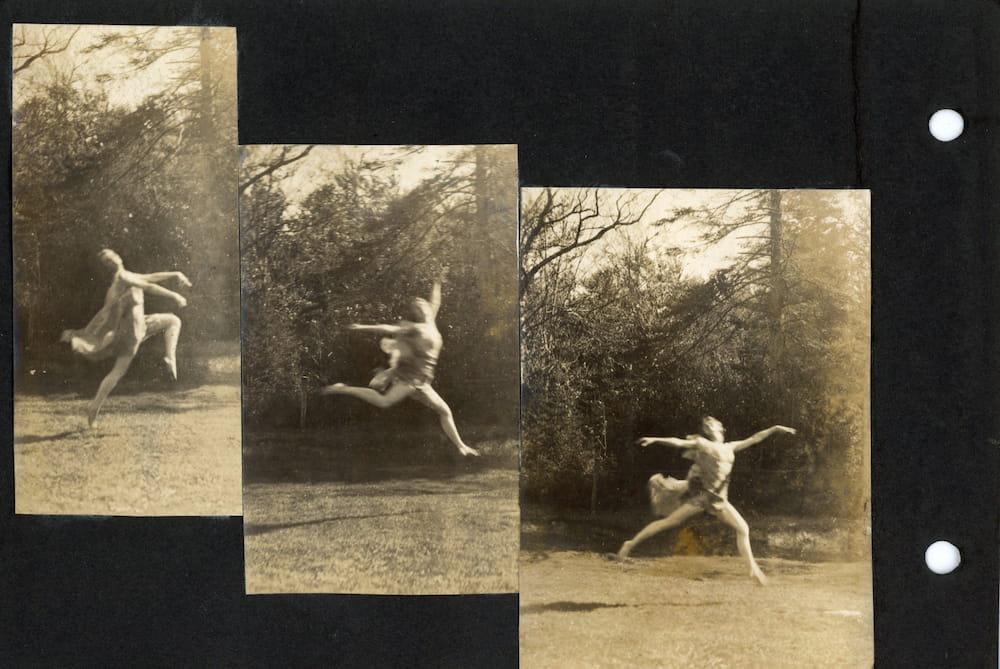

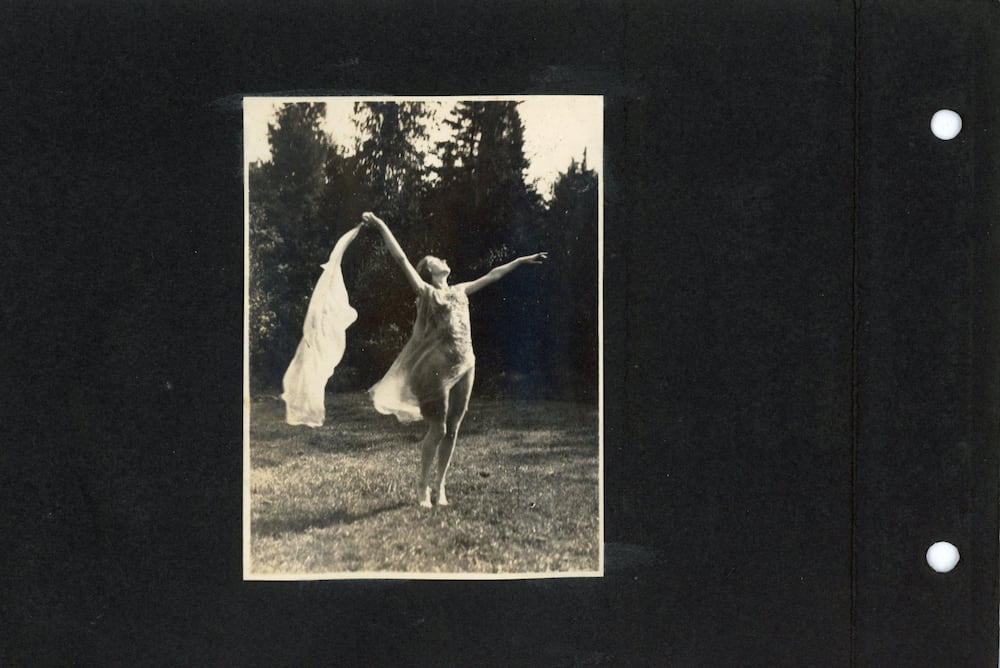

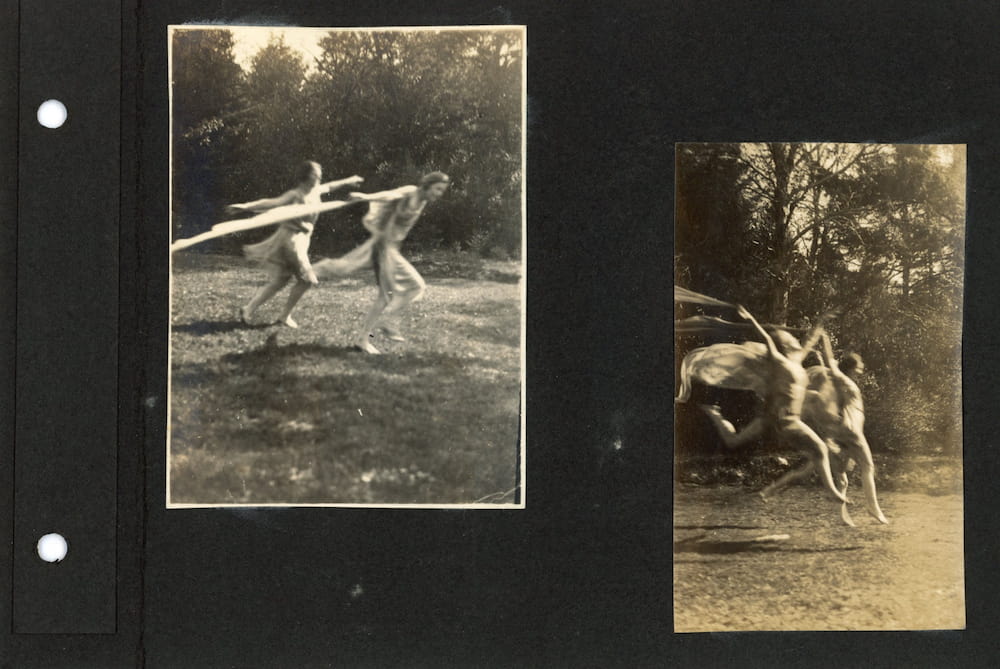

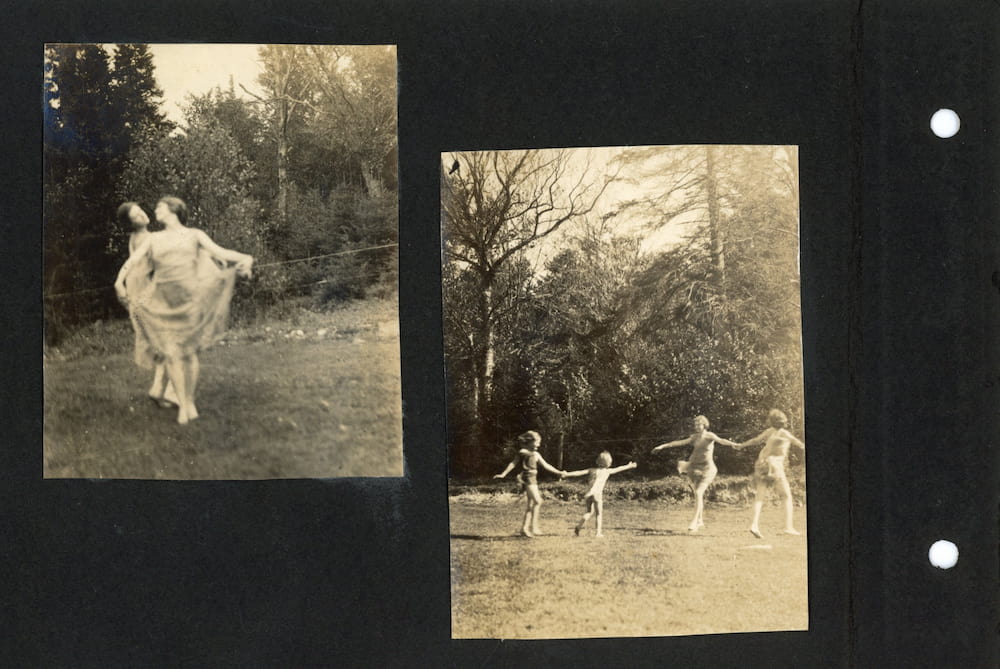

These pages from an album belonging to Wharton and Letty Esherick document the first summer that the couple spent at the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics in the Adirondack Mountains. The setting is the lawn above Upper Chateaugay Lake, where rhythmics classes took place. Participants danced in the grass, barefoot and bare-legged, to classical piano music. The gauzy costumes that they wore extended the flow of expressive movement from their bodies outward.

Several of the photographs show Wharton Esherick taking part in rhythmics exercises as the only man in the group. This event was likely a rarity. While in camp, Esherick mainly focused his energies on his own, less feminized forms of creative expression: drawing, painting, and woodcarving.

Pictured here: Scanned pages from an Esherick family album, Delight Weston and photographer(s) unknown, 1920. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.