Today, we can digitally manipulate the size of an image with the simple click and drag of our computer mouse or trackpad. We can fit images to billboards, books, and stamps, scaling their size up or down with ease. Resizing images was even taken to a comical extreme in 2015 when a world record was set for the smallest color picture ever printed– it’s invisible to the naked eye, so you have to view it through a special microscope.

When Wharton Esherick was actively printmaking in the 1920s and 1930s, decades before the advent of modern computing, manipulating an image’s size and scale was a complex process involving photographic technology, chemistry, exacting manual skill, and craft knowledge. However, during his own lifetime, the need to resize prints was rarely a concern for Esherick. He was a skilled enough printmaker to carve wood blocks ranging from large posters advertising plays at the Hedgerow Theatre to small, decorative capital letters for books in which his illustrations were published.

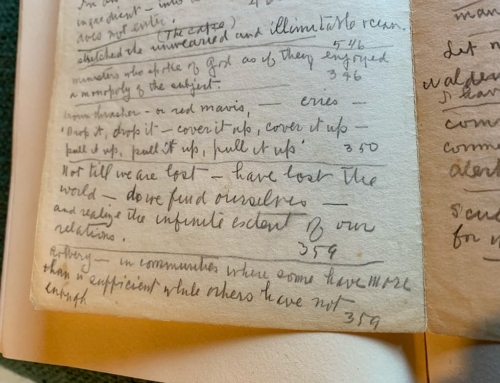

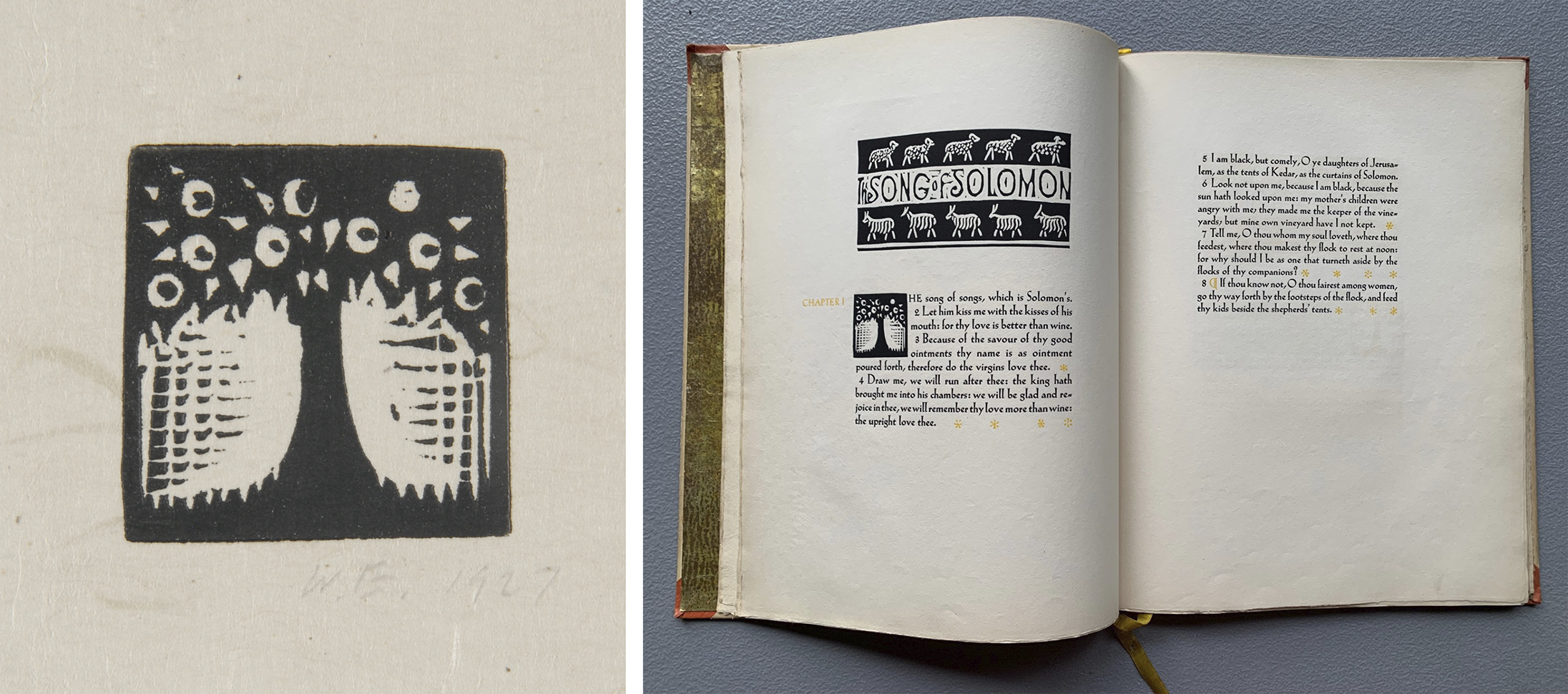

Esherick’s Illustrated letter “T” in the shape of a tree from Song of Solomon.

Things could get a bit more complicated for Esherick when he was repurposing objects. But, he liked the challenge and repurposed things quite commonly. Spokes of a waterwheel became beams in the 1926 studio and hammer handles became chairs strapped with canvas conveyor belting beginning in the 1930s. Fitting a found object to a new purpose is a different kind of challenge from building something from scratch that is designed to be fit for purpose. As such, it took roughly a decade for Esherick to perfect his hammer handle chairs. In the same way Aaron Coleman’s waterwheel dictated the size of Esherick’s Studio, the hammer handles determined how Esherick could design and build the chairs.

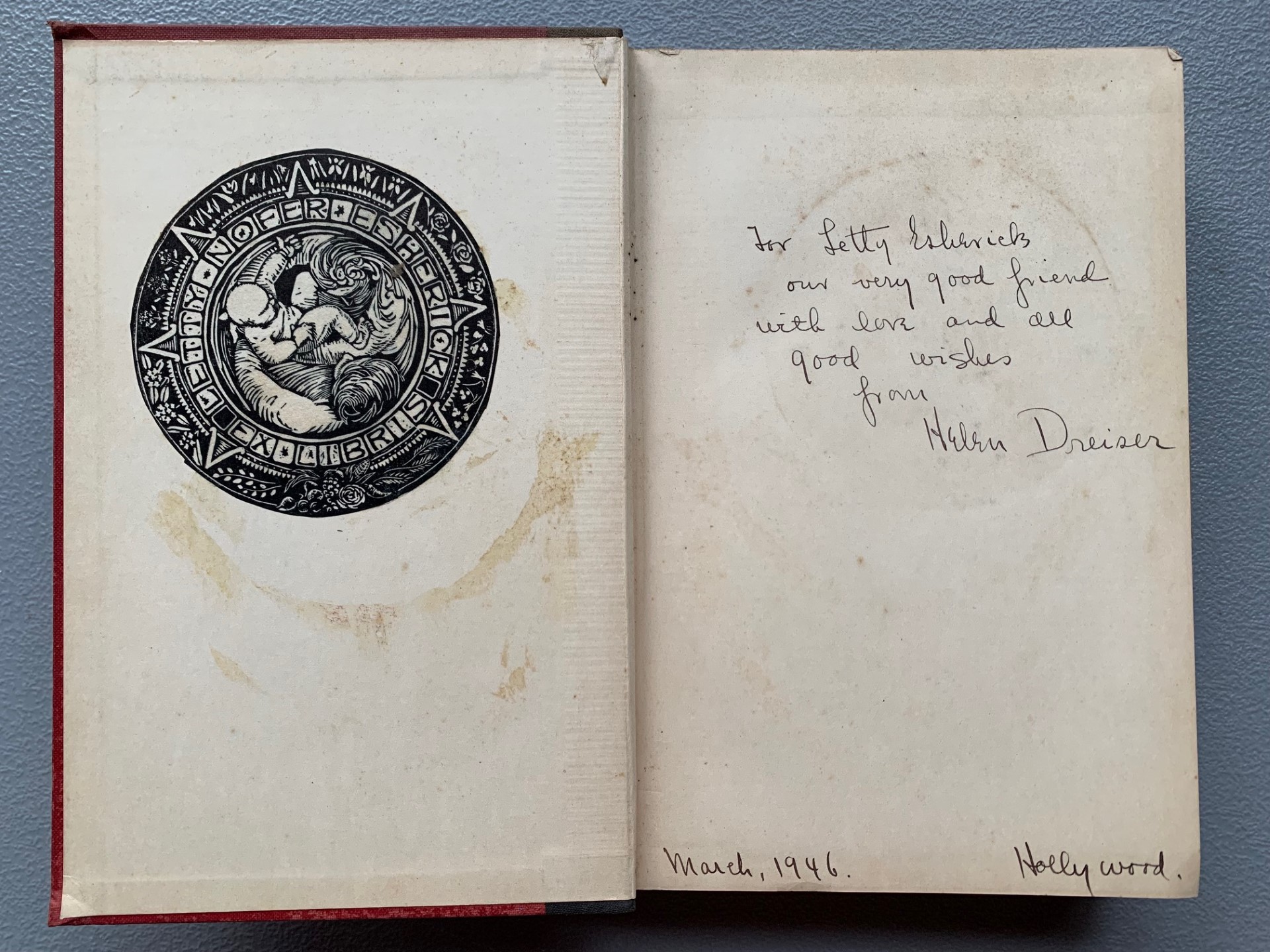

To create a bookplate for his wife, Letty Nofer Esherick, the artist repurposed a woodblock from his first commission, Mary Marcy’s Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk (1922). Esherick took the final print from this book called “A Trinity,” a circular print that depicts a couple enveloping a young child, and carved another block to fit around it. Esherick worked a blank center into the second block to leave room for the original, and carved a decorative border for it with plants, flowers, and blocked letters reading “Letty Nofer Esherick Ex-Libris.” Did Esherick originally carve this block with the intention of using it later as a bookplate for Letty? Might this print be less about the content of Marcy’s daring book of rhymes about evolution and intended instead as a depiction of Wharton and Letty cradling Ruth, their newborn daughter?

Left: A Trinity, 1922. Woodblock Print; Right: Letty Nofer Esherick Bookplate, n.d. Woodblock or zinc plate print.

While the original print “A Trinity” was carved to fit Mary Marcy’s publication, the print became too large to fit into a book once Esherick transformed it into a bookplate for Letty by adding a decorative border. During this transformation, the new border added an extra four inches in diameter to the original print. The size of this new print presented a fundamental problem: a bookplate is meant to fit in the inside cover of a book!

Carved block for A Trinity and carved block for Letty Esherick’s bookplate.

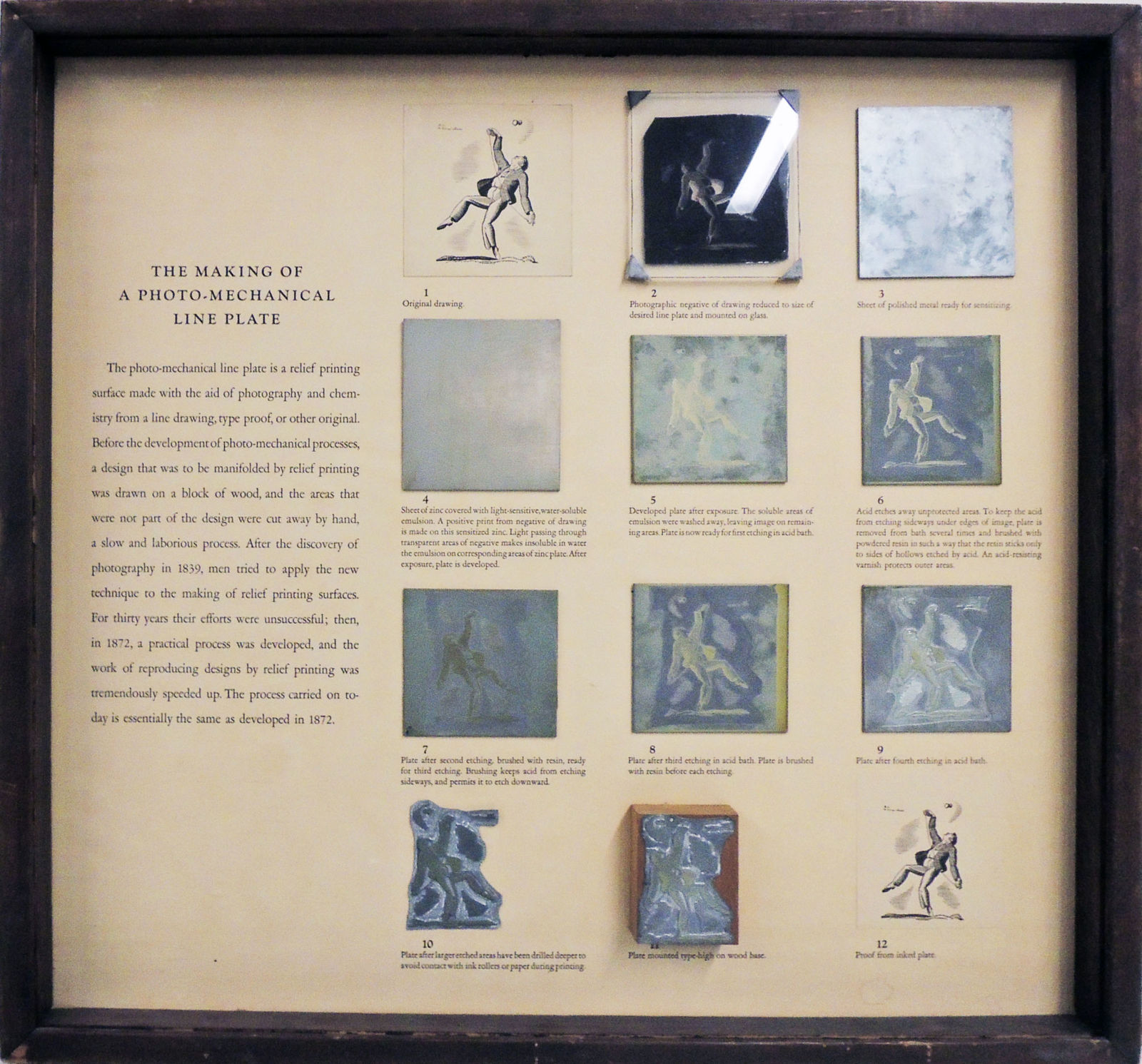

A process called photomechanical reproduction, and specifically photoengraving, was used to resize Letty Esherick’s two-block bookplate. Photomechanics resized Letty’s bookplate by reverse engineering a smaller zinc plate from a woodblock print. The process begins from an original print and transforms it into a photographic negative, a photograph on a zinc plate, and finally an etched zinc plate before a new, smaller print can be made.

4 inch photoengraved zinc plate (left) and 9.5 inch woodblock for Letty Esherick’s bookplate.

Photomechanical printing began with the advent of daguerreotypes in the first half of the nineteenth century. As photography developed through the century, it provided a means for reproducing images of illustration for books and magazines, maps, and famous paintings and other fine arts at an affordable cost for the growing American middle class.

In addition and on the other side of the spectrum, art photographers like Alfred Stieglitz used a similar photomechanical process known as photogravure for his publications Camera Notes (1897-1903) and Camera Work (1903-1917). While this was a popular process that flourished with art photographers in the early twentieth-century, it was brought to a halt during the second world war as costs for materials became prohibitive, before a revival in the 1960s by photographers such as Paul Strand.

Advertisement for Chestnut Street Engraving Co. from the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, April 11, 1922.

Resizing and reproducing Letty Esherick’s bookplate would have likely happened at an engravers studio. The first step would be Esherick bringing or sending them a print of Letty’s bookplate to be photographed. The print would be photographed on a glass plate that would dictate the size of the reproduced zinc plate. Otherwise, the print’s size would have to be manipulated with an enlarger after being photographed. An enlarger, like a projector, operates with light and the play of distance. Once the image has been captured on the glass plate it’s referred to as a line negative.

It’s important to remember that a printing block or plate will be the reverse of the image you’re printing. When Esherick was carving his woodblocks, he would have to be thinking about his design in reverse as he carved. Things get even more complicated when you’re photographing a print for reproduction. Since an image gets reversed as it passes through a camera lens, this reversal needs to be corrected so the final print is not backwards. Thus, the photographic negative needs to be lifted off the glass it was captured on by a skilled worker known as a turner and flipped over onto another glass plate. This operation depends entirely on the precision and care of a negative turner’s hands. Turning the negative over situates the image in the correct orientation for the new plate to print in the right direction.

Teaching illustration of the photo-mechanical line plate process. Courtesy of the Graphic Arts Collection in Special Collections of Firestone Library, Princeton University.

A zinc plate is then coated with an emulsion of albumen and ammonium bichromate that makes the plate light sensitive. The now reversed line negative on glass is mounted to this zinc plate. Heavy pressure forces the metal into contact with the line negative, and the whole thing is exposed to light. As light passes through the photographic negative onto the metal plate, the albumen hardens, adheres itself to the plate, and becomes insoluble in water, essentially transferring the photographic image to the zinc plate. The zinc plate is now developed.

Developing the zinc plate involves inking with a greasy etching ink that is evenly distributed over the plate’s surface. The ink dissolves the soluble areas of the albumen, and once the plate is washed with warm water, only the hardened albumen covering the image being reproduced remains. At this stage, we have a zinc print. Since the photographic negative was turned over, the image on the metal plate will correspond to the carving on Esherick original blocks.

Once the zinc plate is fully dry, it’s covered with a resinous powder that adheres to the greasy ink on the hardened albumen. The powder, ink, and albumen form an acid resistant material that protects the design once the zinc plate is dipped into an etching bath of acid.

Once the areas of the plate Esherick didn’t want to be printed had been thoroughly etched away by the acid, the design stood out in relief. The relief design is then cut out from the rest of the zinc plate and mounted onto a piece of wood and readied for printing. Now, Letty’s bookplate has been reverse engineered onto a small plate of zinc at a size fit for purpose: printing on the inside cover of her books! Utilizing photoengraving to manipulate the size of Letty’s bookplate shrunk the print from nine-and-a-half inches down to four inches.

Zinc plate of Letty Esherick’s bookplate mounted onto a wooden block.

We can find Letty’s bookplate stamped into a few books onsite today. For example, Letty marked a copy of Theodore Dreiser’s autobiography Dawn gifted to her from the author’s wife Helen in 1946. We can also find Letty’s bookplate inside a four act play called Love Possessed Juana written by the dancer Angna Enters and published in 1939. The fact that she marked these two books in particular highlight that Letty continued an independent friendship with Dreiser and his family after her separation from Wharton, as well as to pursue her deep interest in dance.

Letty Esherick’s bookplate as seen in her personal copy of Theodore Dreiser’s Dawn and inscription from Helen Dreiser on the opposite page.

Some of Esherick’s other prints were resized for various purposes as well. The Hedgerow Theatre used prints Esherick made of the building’s interior and exterior for playbills and other promotional materials that were likely reduced in size with a similar photomechanical process. Additionally, WEM’s collection includes two other zinc plate prints that feature dancers from Gardner Doing Dance Camp. These existing zinc plates seem to suggest other woodblock prints were likely resized with photoengraving for use in the camp’s promotional materials.

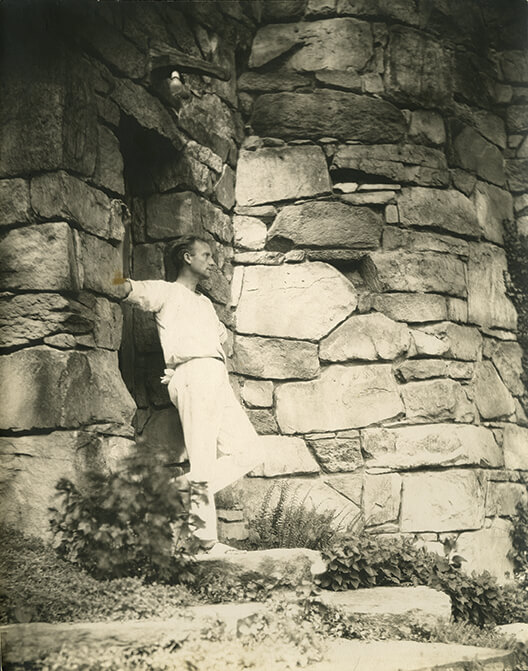

Consuelo Kanaga (photographer), Esherick at his Studio Entrance, 1927. Photographic print. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection

We know that Wharton Esherick was no stranger to the art of photography. He was known to be friends with photographers such as Marjorie Content and Conseulo Kanaga, and even to have run in the same circles as Alfred Steiglitz. Moreover, Esherick often sent out rather professional looking photographs of his sculpture and furniture to inquiring minds. Looking toward the zinc plates in our collection, however, illustrates other ways Esherick engaged with the medium.

To learn more about photomechanical printing:

» Watch a film on photoengraving made by Horan Engraving in the 1950s

Post written by Manager of Collections and Public Programs Ethan Snyder.