Single Music Stand, 1960, Cherry, walnut, 44 x 18.25 x 20, from the Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum. Photo by Eoin O’Neill.

Captain’s Chair, Wharton Esherick, 1951, Walnut, cherry, laced leather seat, 29.5 x 20.9 x 20.9 inches. Photo by Eoin O’Neill. Collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

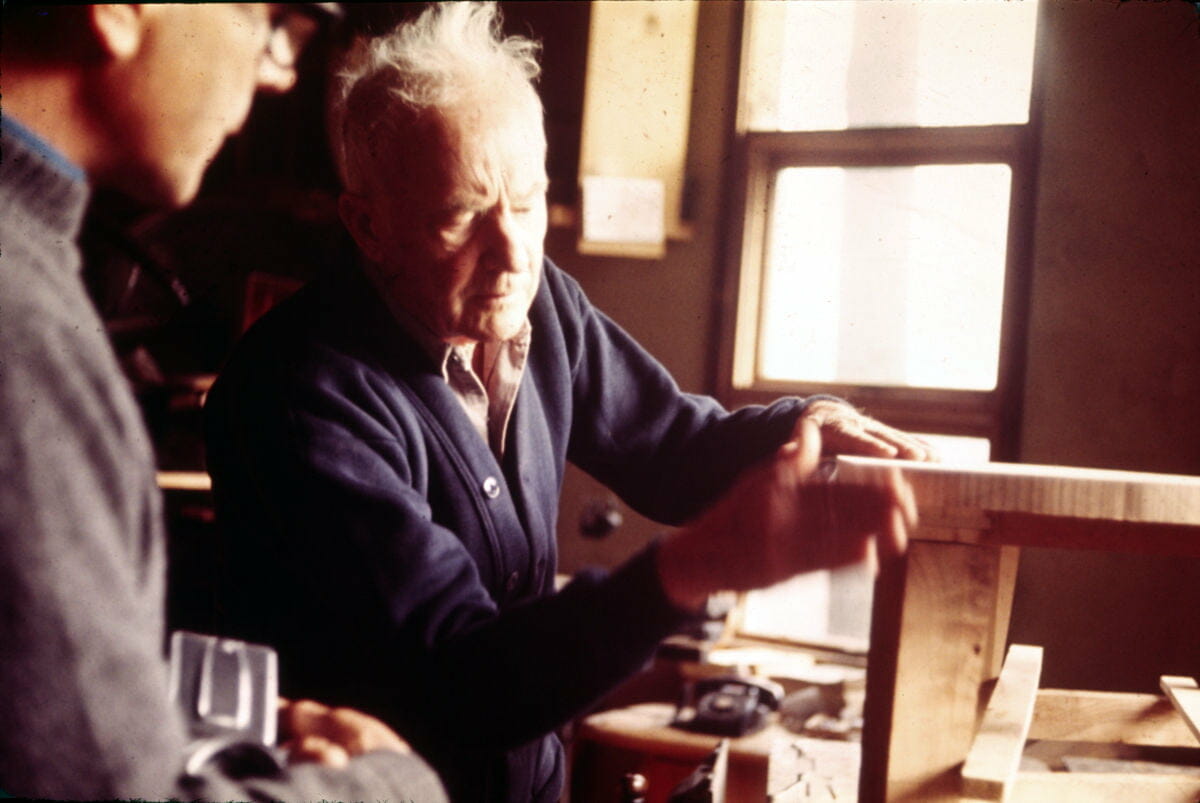

Curved and sculpted edges are a signature feature of Wharton Esherick’s furniture. Esherick approached furniture as sculpture and, as such, treated each object he created with attention and care. The hand of Esherick – as artist, as craftsman, as sculptor – is so prominent in his work it may feel antithetical to ask if such work could be manufactured, and even more surprising to learn that Esherick explored the possibility himself.

In our recent, Spotlight Talk: A-Z of Wharton Esherick and American Studio Furniture we shared a selection of bills, receipts, and other communications from our newly discovered archives that illuminate the business side of Esherick’s career, particularly from the later decades of his life.

These client files often bring up as many questions as they answer, especially when it comes to Esherick’s attempts at having two designs produced outside of his own shop – the Music Stand and the Captain’s Chair.

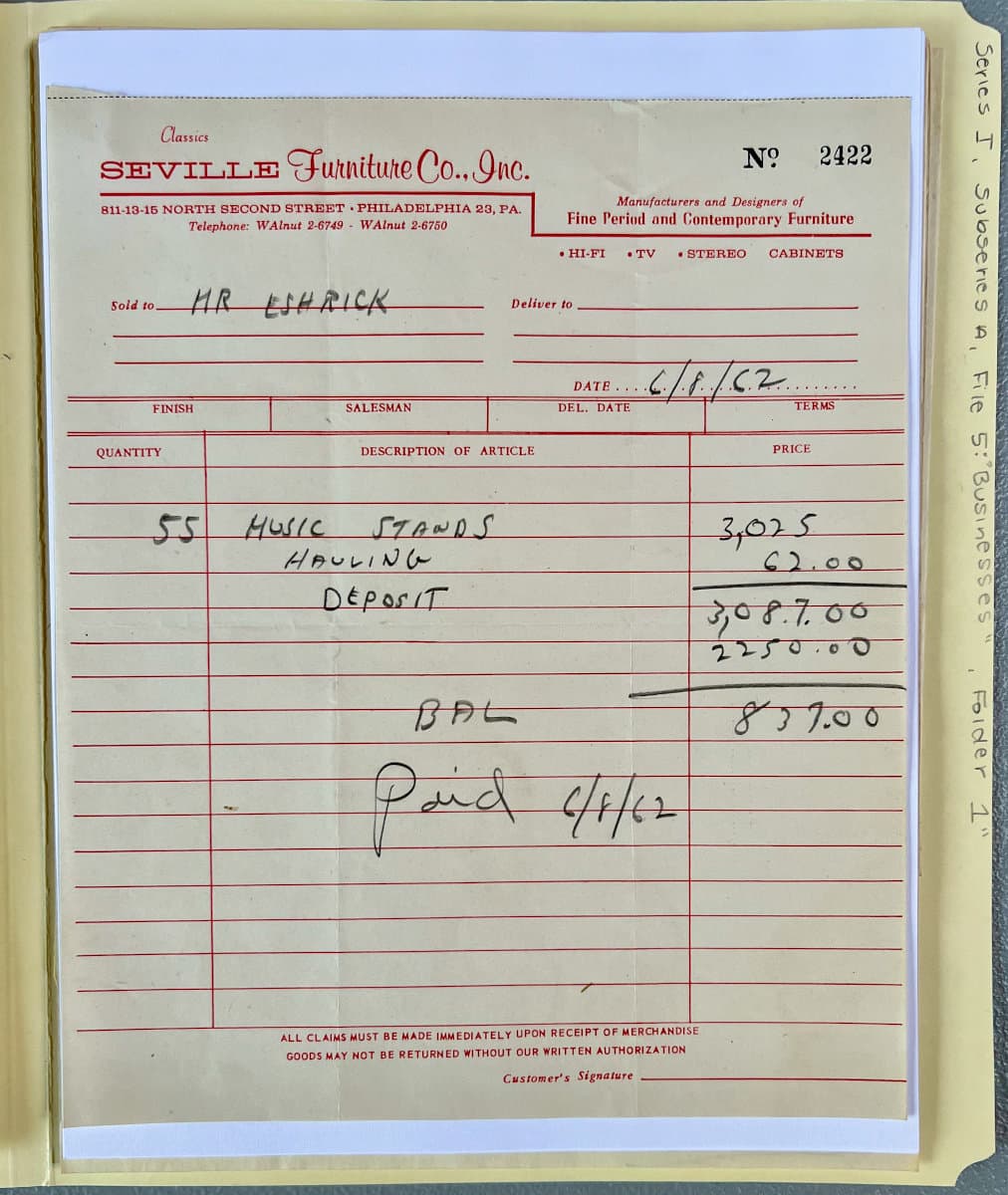

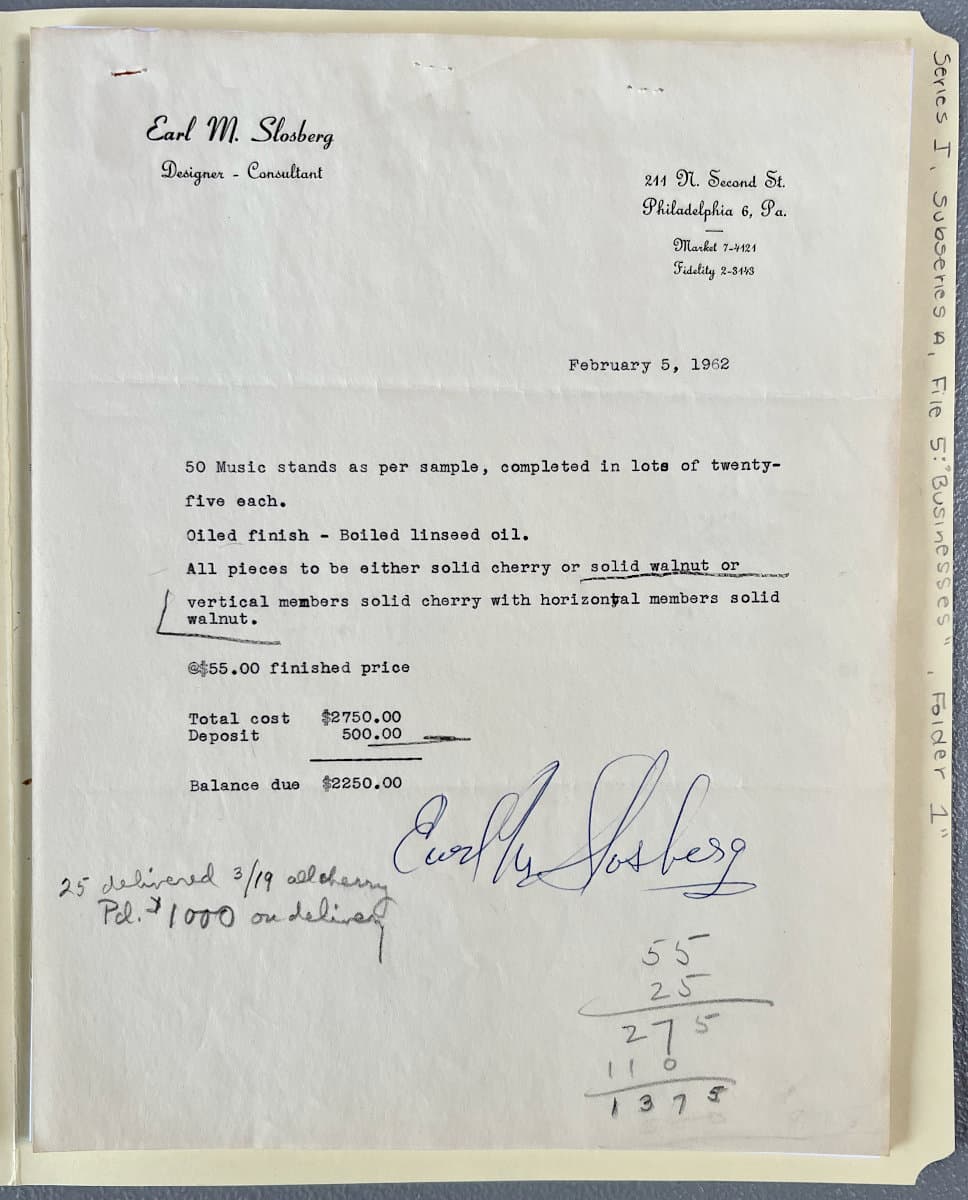

Music Stand Letter from Earl Slosberg to Wharton Esherick, 1962. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection.

Esherick pursued scaling up the production of the music stand at the suggestion of his good friends and patrons Nat and Rose Rubinson. He had designed the first music stand for Rose, a cellist, which was later included the Brussels World’s Fair and Esherick’s retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in New York City. This prototype music stand was also highlighted in our recent exhibition, One Object, Many Stories. Esherick subsequently made a batch of three more music stands, one for himself, one for Alice Seiver, and one for George Rochberg, both of whom were friends and patrons of Esherick’s. Hoping to lower the price point for this design to something more people could afford, Esherick worked with the Philadelphia-based Seville Furniture Company and Designer/Consultant Earl Slosberg on the production of around 50 music stands. While the details are unclear, we do know that the project fell apart. Esherick was unsatisfied with the quality of the work, and ultimately took all of the music stand pieces back in parts to be refinished and assembled under his own supervision.

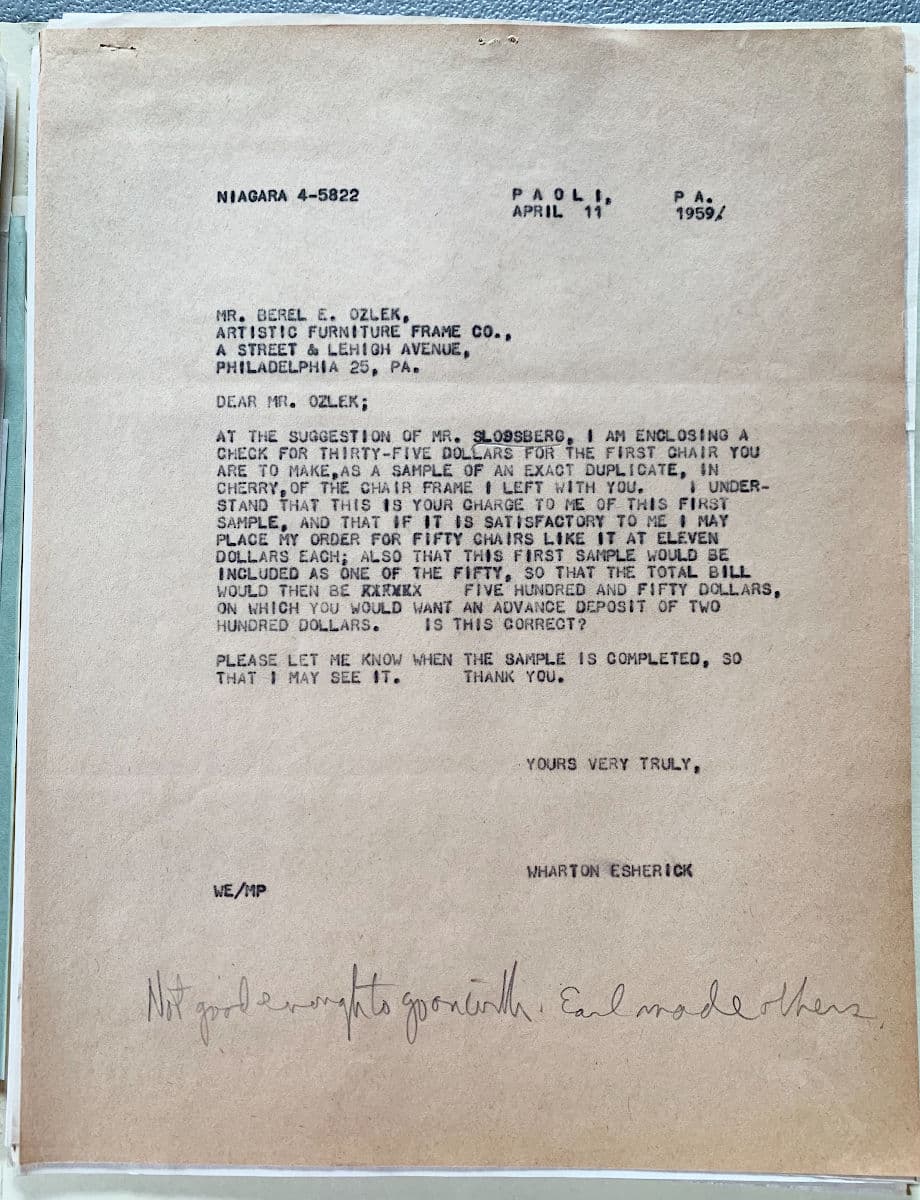

Our archives also include documents regarding the production of Esherick’s Captain’s Chair by the Artistic Furniture Frame Company, again in consultation with Earl Slosberg. On one letter to the company a handwritten note at the bottom reads “Not good enough to go on with. Earl made others.” Unlike the music stand, Esherick was able to find an alternate route in creating the captain’s chairs at a reasonable cost by working with his frequent collaborator John Schmidt. Schmidt had the arms of the chair steam-bent elsewhere, creating small batches of chairs, about six at a time, based on Esherick’s original. As with other collaborators and workshop assistants, Esherick was happy to have others construct the forms, particularly for a design he was repeating, while leaving the final sculpting to him.

Esherick’s efforts to scale-up production point to the ever-present tension between his creative desires and the practical and financial pressures of making a living through his artwork. Esherick rarely charged enough for his own work, instead making just enough on each piece to start the next one, never really paying himself a reasonable wage. In interviews like his 1966 conversation with Sam Maloof and Donald McKinley for Craft Horizons magazine, Esherick spoke in a way that was both practical and idealistic, simultaneously aware of strategies for marketing his work – “I usually sign everything because I remember someone – I think Chippendale – signed everything, and his furniture became tremendously valuable because of it,” – while holding to his ethos of living with furniture as a form of sculpture and centering the beauty inherent in wood.

Esherick wasn’t a purist when it came to machines and woodworking. In his 1966 Craft Horizons interview, Esherick emphatically pushed back on the label ‘handcrafted’ stating:

“This thing you call handcraft, I say, ‘Stop that thing.’ I use any damn machinery I can get hold of. The top of this table was all done by machine. We didn’t rub it by hand. Handcrafted has nothing to do with it. I’ll use my teeth if I have to. There’s a little of the hand, but the main thing is the heart and the head. Handcrafted! I say, ‘Applesauce! Stop it!’”

As for large-scale production however, Esherick found that in the case of the music stand and the captain’s chairs it couldn’t be done. In the end, the quality of the final object, whether handled by machine or hand, Esherick’s or others, those undulating surfaces and forms could not be created to his satisfaction outside of his supervision. The treatment of the material, while it may have been close in measurement and form, had ultimately lost some quality outside of his care. The pieces were more than their design, more then their precise measurements, more than the sum of their parts.

The Wharton Esherick Museum has rich archives that include Esherick’s personal and business papers, his correspondence with leading figures in American modernism and the studio craft movement, as well as an extensive oral history collection. The archives are open to researchers by appointment. For more information, please contact Research Director Holly Gore at [email protected].

Post written by Deputy Director of Operations and Public Engagement Katie Wynne

May 2023