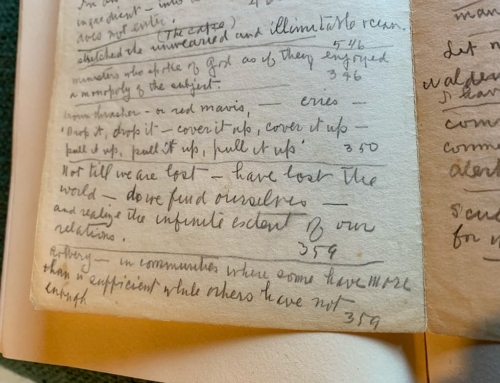

This conversation has been reprinted with permission from “The New American Craftsman: First Generation ” by Wharton Esherick, Donald McKinley and Sam Maloof, 1966. Craft Horizons, Volume 25, Number 3, pages 15-19. Copyright 1966 by The American Craft Council.

WOOD

SAM MALOOF: What would you say to a young fellow, Wharton, if he came to you and wanted to work the way you do?

WHARTON ESHERICK: There’s two things I say. “Listen, if you go into this thing that I’m doing, you’ll have a hell of a struggle – but you’ll have fun.” And the last, the very last thing I say – usually students come with their teachers – is, “You’re never going to get any place in this world unless you get away from those people over there – your teachers.” All the teachers I had were good, marvelous teachers, but I wanted to get rid of them. I had too much conceit, that’s all. I wanted to do it; I didn’t want them to advise me. I’d had plenty of teachers in painting. I could paint like Sargent painted, like old Vermeer, like any of those painters. But I couldn’t paint like Wharton Esherick. I was over-educated as a painter.

SAM MALOOF: How did you start making furniture?

WHARTON ESHERICK: I began to make furniture for myself, and people would say, “Wharton, sell that thing.”I’d sell the piece, and I began to think, “if I can sell my furniture and can’t sell my paintings, why don’t I make some more furniture?” That’s how it began.

DONALD McKINLEY: Wharton, are you doing any interiors now, or just furniture?

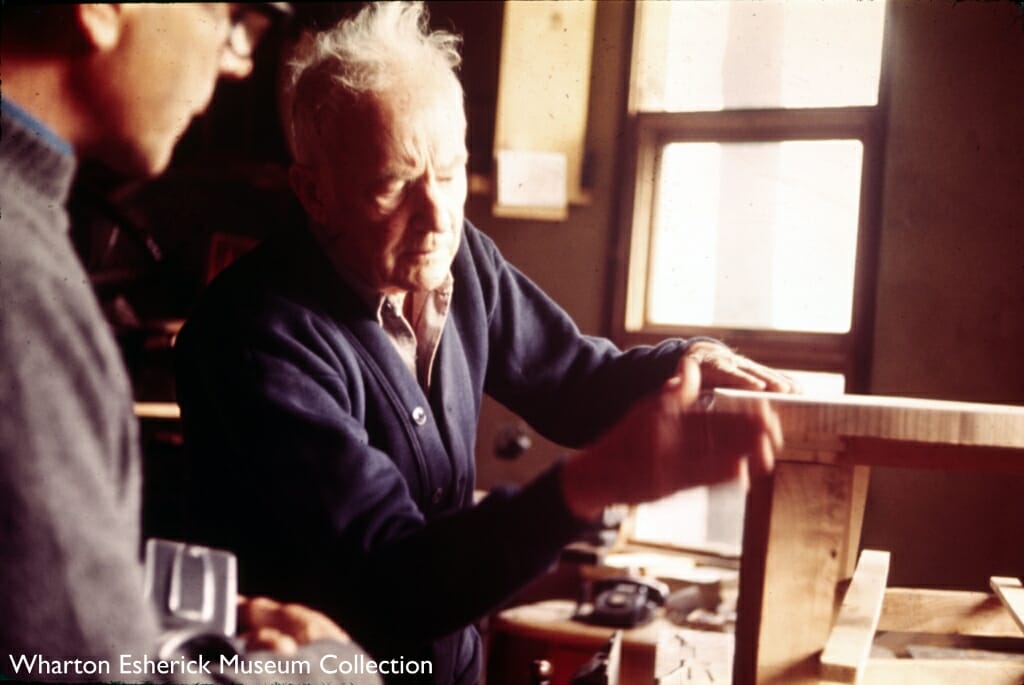

WHARTON ESHERICK: Mostly furniture. I’m busy with furniture all the time. But I’ve got to slow up. I’m seventy-eight years old, you see. I have three boys over in the shop, and we’re busy now on the three-legged stools. I have to do all the seats myself, though. They just can’t make them.

DONALD McKINLEY: Do you have the same people working all the time, or do they come and go?

WHARTON ESHERICK: This one boy I have over there now, the other day I said to him, “Billy, you came to me when you were fourteen years old.” He said, “I came to you when I was twelve.” And he’s now fifty-two. Right now he’s going through a worrying stage, because he says, “I don’t know what I’m going to do when you die, Wharton.” But I say, “I ain’t dying yet, Billy, I ain’t dying yet!”

SAM MALOOF: At this conference in Buffalo that Don and I just came from [see “Craftsman-Designer-Artist,” page 83], how many craftsmen there actually work and make a living at their craft? Besides us, I can think of very few. People are so afraid to go out and try what they were trained to do. They take up teaching as security, and the practice of craft is a fringe benefit.

WHARTON ESHERICK: That’s so true. They’re overdoing the teaching. When I’ve been asked to teach, I say, “I make, I don’t teach.” I say, “Bring your class out here. If they can’t learn by looking at the thing, all my chattering will never teach them.”

SAM MALOOF: I feel that way, too. I’ve been asked to teach and have said “no, thank you.” What happens instead is that classes – from UCLA, Los Angeles State, Long Beach State – call up and ask, “Can we come out and see what you’re doing?”

WHARTON ESHERICK: I say, “Come and look at this stuff if you want to. I can talk about it if it’s in front of me.”

SAM MALOOF: A lot of times they’ll say, “Can we ask a question, or is it a secret?” There are no secrets in joinery. It’s a matter of figuring it out. I know without any formal training. I just picked it up, and I’m still learning.

DONALD McKINLEY: Wharton, how long have you made your living from furniture? You started as a painter and made the switch.

WHARTON ESHERICK: I started as a painter and had exhibitions in Alabama, Washington, D.C., and Chicago. Then I found I wasn’t painting like Wharton Esherick ought to paint, so I started with sculpture, then with furniture. I haven’t painted in thirty years.

DONALD McKINLEY: You live pretty well, Wharton. You’ve a lot of comfortable things here.

SAM MALOOF: You ought to sit in this chair – it’s certainly comfortable.

WHARTON ESHERICK: That’s the one I actually made myself. It was number one, the model, and nobody’s going to get it away from me. Whenever I make a chair design, I always keep one for myself.

SAM MALOOF: I don’t have all my prototypes, but I have a lot of them for use as samples. Recently, a woman in Chicago wanted one of the chairs in a show – but lower and without any spindles. She asked if I’d send a drawing, but I told her I’d make a prototype and ship it. I made a full-size chair and shipped it – not a model, a real chair. When I first started, I’d make a drawing, then a little model. Then I’d buy sugar pine or redwood and make a prototype – not even dry dowel it, just nail the piece together to get a picture of it. I decided this was a waste of time – that I might just as well make the prototype in the material that was going to be used – a completely finished piece. I shipped this one to the lady in Chicago because I felt that if she wanted twelve of them, she ought to sit in the chair first. She ordered the twelve.

DONALD McKINLEY: I noticed in the catalog from the Museum of Contemporary Crafts’ show of your work that some things were listed as signed and some unsigned. Do you deliberately leave some unsigned?

WHARTON ESHERICK: I usually sign everything because I remember someone – I think Chippendale – signed everything, and his furniture became tremendously valuable because of it.

DONALD McKINLEY: If they pay for the signature, why fight it? A lot of patrons of the arts and crafts are not really collecting work; they’re collecting autographs.

SAM MALOOF: We were talking about the kind of clientele we get. So many think the only ones who can afford handmade furniture are the people with lots of money. I say, “Really, some of my customers don’t have much money at all. They’re young people who have seen a piece, love it, but confess they don’t know how to pay for it. So I tell them if they really want a piece, they can send me so much a month and I’ll make them one.”

WHARTON ESHERICK: Those are the people you’d almost give the chairs to!

DONALD McKINLEY: Did you go to Wilmington to see the Northeast regional section of “Craftsmen USA ’66”? There were several chess sets – one in copper and brass that was quite nice.

WHARTON ESHERICK: I object to metal because I think it’s uncomfortable. That big desk over there had an aluminum top once, and I took it off.

SAM MALOOF: People have asked me, ” Why don’t you use other materials? Why not introduce plastic?” My comment is, “If you’ve ever worked with wood, you don’t want to use other materials.”

WHARTON ESHERICK: Wood is intimate, it’s alive. Plastic just won’t do. I’ve got a wood man who will call me up and say, “I’ve got a nice piece of walnut – I’ll cut it the day you come down.” And he’ll cut it in front of me.

DONALD McKINLEY: Do you air dry it?

WHARTON ESHERICK: It’s all air dried out there in my woodshed – one year to the inch. To show you how wonderful this wood man is, when he cut into an oak tree and found it was curly oak, he said to himself, “I’m not giving that to some of these fellows to make steps and stuff like that – this goes up to Esherick.” One day I saw him on the road, and he says, “You don’t know it, but you’ve got two hundred feet of curly oak in your woodshed. You don’t owe me anything.” He wouldn’t sell it on the market, but he’d give it to me. So I made him a table. I’d never seen curly oak in my life, and he’d never seen it though he was a wood man. Did you ever use padouk? It’s the damndest wood you ever saw – dulls all your tools. I did a whole room full of it once – furniture, doors, everything. It was beautiful. But a year afterwards it was black. It turns, and you can’t keep the color.

SAM MALOOF: Cherry works beautifully, but it’s so dry in California that it expands and contracts much more than walnut.

DONALD McKINLEY: There’s something about foreign wood that intimidates craftsmen. If the wood costs a certain amount, they think, “I’ve got to be real careful.” And it turns out that somehow the piece of furniture is not as direct as it should be, because of the concern about how precious the wood is.

WHARTON ESHERICK: You shouldn’t have that feeling. If a piece of ebony cost me ten dollars, I’d throw it in the fire if it didn’t do what I wanted it to do.

DONALD McKINLEY: I saw the dates 1929 and 1962 on the desk you said originally had an aluminum top. What possessed you to make an aluminum top? Wasn’t that a little modern for 1929?

WHARTON ESHERICK: I don’t know why now. But I went to the aluminum company, and a man who was evidently the president said, “You’re talking about aluminum furniture, I’ll show you some.” In his office were six Colonial chairs and a big Colonial desk which looked like mahogany. “It’s all aluminum,” he said, “look at it.” And I said, “You’re just a damn fool. You’ve got a good product and then you go fake it and ruin it.” He said, “Don’t you like it?” And I told him, “It’s awful, awful! What do you think I wanted an aluminum top for? Because in itself it’s a nice product.” But then, as it turned out, it was too cold – wasn’t my top.

DONALD McKINLEY: Wharton, do you refinish your tables and things?

WHARTON ESHERICK: This table has been used and used and used. And wet glasses always used to spot it, no matter what I would do. So finally I got the idea of epoxy, and it works. You can spill alcohol on it. You can put a hot coffee pot on it. There’s only one drawback: you have to watch it, or you’ll get the most tremendous shine. You have to rub it down with a pumice stone and crude oil.

DONALD McKINLEY: There are some people who say, “I’m going to be true to my craft. I’m going to use my granddaddy’s finish, my granddaddy’s techniques.”

WHARTON ESHERICK: Use your granddaddy’s tricks now, and you’d be crazy. The glue your granddaddy used, for instance, isn’t worth a damn. I use Weldwood glue – a dry resin type. There’s another type for something you want to do quickly, but the real Weldwood takes about twelve to fifteen hours to dry. That’s the best. You have to use it at seventy degrees.

SAM MALOOF: Wharton, there aren’t too many people making furniture – really making a living at it like we are. I think the reason is they can’t produce enough to make a living. They treat a chair like a painting or a piece of sculpture, working on it for three, four months. But you can’t do it this way. You’ve got to turn these things out; you can’t expect to sell them for a thousand dollars.

DONALD McKINLEY: Maybe we’re all nuts. Maybe handcrafted things are an anachronism. Maybe things made by hand should be just like art – another thing that’s made by hand.

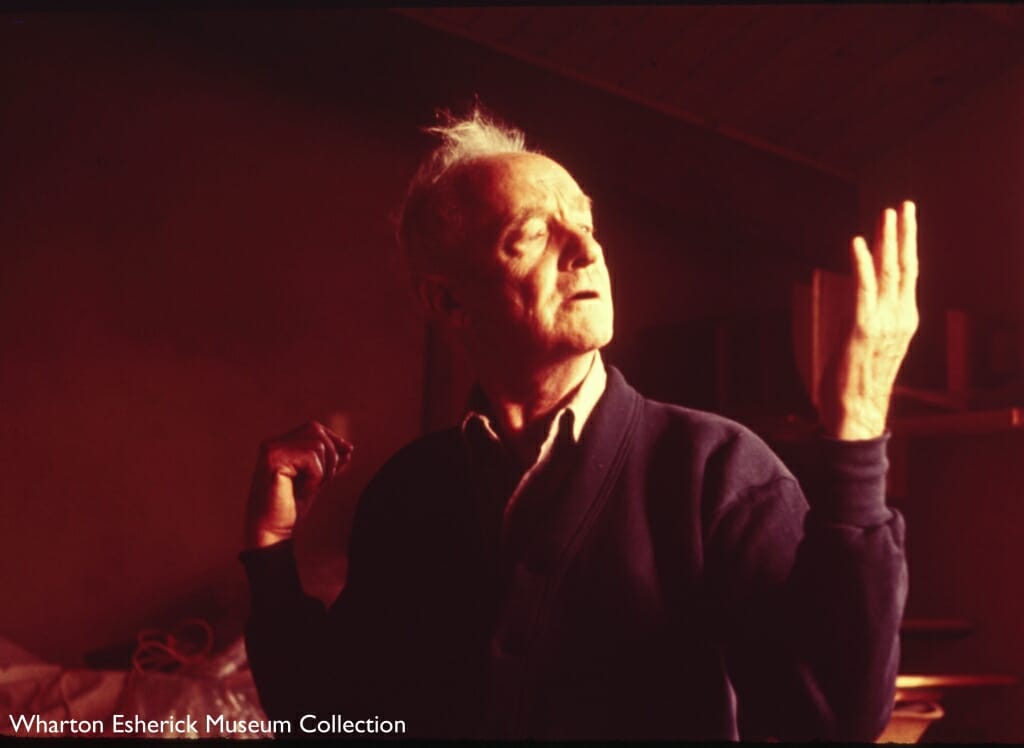

WHARTON ESHERICK: No, I’m going to step in on that. This thing you call handcraft, I say, “Stop that thing.” I use any damn machinery I can get hold of. The top of this table was all done by machine. We didn’t rub it by hand. Handcrafted has nothing to do with it. I’ll use my teeth if I have to. There’s a little of the hand, but the main thing is the heart and the head. Handcrafted! I say, “Applesauce! Stop it!”

SAM MALOOF: What you mean is “individually supervised.” Your furniture, Wharton, and that of all of us is really custom furniture – made to order. To make a piece we use whatever tools we can.

DONALD McKINLEY: Custom is a good term, but on the other hand it isn’t quite accurate. If you make more than you have orders for and put these pieces in stock, then it becomes limited edition. It’s still “individually supervised,” though. Sometimes that supervision extends to your own hand; sometimes it goes to another man and you tell him. It can even mean that you turn on the switch to a machine. But it’s personal supervision and personal concern.

WHARTON ESHERICK: Turning on the switch is a very important thing.

SAM MALOOF: You know, Wharton, you’ve not overextended your wood at all. You have never made wood do what it doesn’t want to do. What do you think of forcing? Do you object to it?

DONALD McKINLEY: How about that little three-tiered stepstool with the piece of wood that has been steam bent? Isn’t steam bending a belligerent thing to do to wood? You steam it, cook the life out of it, wrap it around and put steel clamps on it, let it dry, and then say, “Now stay there.” Let’s face it, this is forcing wood.

SAM MALOOF: No, to me this isn’t forcing wood, working it out to a paper-thin lip. I’m thinking of some of Wendell Castle’s things where he extends the wood to its very maximum.

WHARTON ESHERICK: What did he make it out of wood for, then, if he’s only after form? There’s no beauty of wood there.

SAM MALOOF: You have to find your own personal way as a craftsman. I recall vividly what you said to me after the ACC conference at Asilomar (1957): “Keep doing what you’re doing.” That’s always stayed with me. You can only do so much and earn so much, but this is secondary. To do what you want – this is the important thing.

WHARTON ESHERICK: If you don’t have joy, are not enthusiastic with what you’re doing, no matter how much dough you’ve got, you’re no good.