“Peter Esherick,” Photo by Marjorie Content, circa 1934.

In the summer of 1937, at the age of eleven, Wharton Esherick’s son, Peter, became the unlikely subject of the author Jean Toomer’s latest manuscript. Best known as a poet of the Harlem Renaissance, Toomer and his wife, the modernist photographer Marjorie Content, were both friends of Esherick, and in that way that artists’ circle operate, Esherick’s son would come to inspire a work of his own. Esherick had known Marjorie Content since 1926; she recalls in an oral history that when she first met Wharton through Henry Varnum Poor, Peter was only a few months old. Thanks to the Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript library, which holds the unpublished manuscript, “Talks with Peter,” we are excited to illuminate Peter Esherick’s relationship with Toomer and Content and the philosophical conversations they captured one summer.

Toomer and Content began a philosophical press, Mill House Press, from their home in Doylestown, PA.

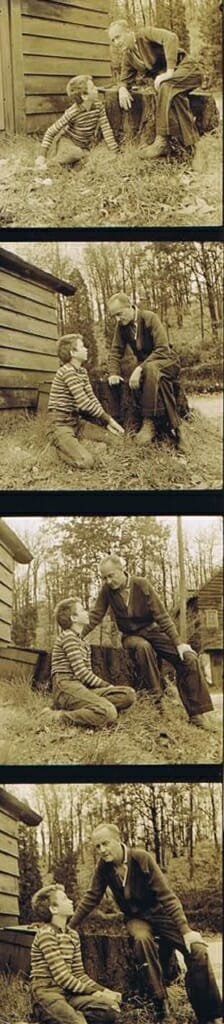

Soon after their marriage—a marriage in part urged by Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Steiglitz—in 1935, Jean Toomer and Marjorie Content settled on a farm outside of Doylestown they named Mill House. Wharton helped the couple convert an old Pennsylvania bank barn into a residence. For July and August of 1937, rather than go to a camp, Peter was sent to stay with Marjorie and Jean. At Mill House that summer, one could find Peter doing farmwork, taking care of the cows, helping the farmhand Ramsey, playing with Jean’s daughter Argy, reading, or having his ritual afternoon discussion with Jean over tea.

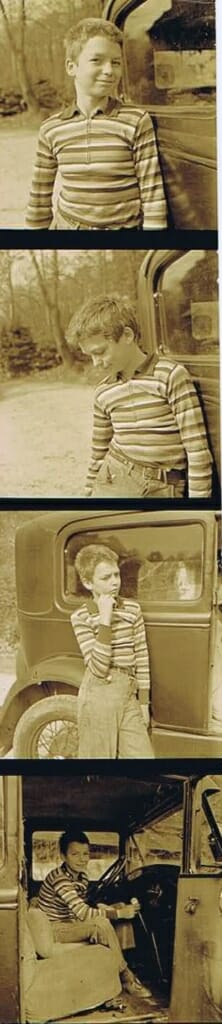

Photos of Peter Esherick by Marjorie Content, undated.

These daily discussions are what would later become the inspiration for “Talks with Peter,” which were never successfully published. “Ah the people of the world, that world of human meaning and good will, which we have labored for and despaired of,” Jean concluding his introductory remarks writes “would most certainly come into being were those like Peter, and the young of all generations, aided to break away from ancient folly and guided toward the natural development of their inherent powers” (5). This manuscript functions as a project to guide its readers toward Toomer’s idea of the fulfillment of inherent human potential, a potential that Peter—at the young age of eleven—brilliant frames as having “one key to a hundred doors” (84). Jean saw great potential in Peter as he came of age, and wanted to use his curiosity and intelligence as an example for all of his generation.

The manuscript opens with the question: “what kind of man are you going to be?” (1). Peter replies that he wants to be a worker, to make “things that others can use” and tells Jean that he already made some things, although only useful to him (4). In the spirit of Wharton, Peter’s creations were made for fun. Jean questions him about the use and misuse of things, and the labor that goes into making them. One of the higher orders of human fulfillment is not only making things, but making things that are useful to others. Where Peter at eleven years of age was making fun things for his own pleasure, Peter in his adult life would go on to create a business in medical technology and make useful things for the good of others.

Thanks to Marjorie Content’s recording of these conversations in shorthand their contents are preserved. As Jean writes in his foreword, without Marjorie, “Peter’s exact words would have been lost” (2). The topics of their conversations range from human resourcefulness, desire, psychology, and prejudice, to the balance of one’s inner life, the fulfillment of human potential, and masculinity, as you can see from Jean’s first question. Although Toomer was steeped in the philosophy of the Russian mystic George Gurdjieff, one cannot help as they read these manuscripts but picture Jean as a Socratic figure as he tells Peter, who he affectionately calls “Pete,” his discursive methods: “asking you questions that will lead you to see the point” (137). It is by this Socratic method that Peter wades through abstract and complicated ideas on human nature, morality, and the search for truth.

Wharton Esherick and his son Peter at the Sunekrest farmhouse. Photos by Marjorie Content, undated.

Peter arrived at Mill House outside Doylestown on July 5th as he recalls the exact date to Jean during one of their conversations. That evening Peter played croquet in the yard and, to belatedly celebrate the Fourth of July, set off several whole boxes of fireworks that he saved up the money to buy. Peter displays a brilliant sense of curiosity and great interest in these conversations with Jean as on his second day at Mill House, made it a point to make himself present, asking if they would have another talk that day, too; the two continued these talks through the duration of Peter’s stay, and “really began to make something of it” (2).

In his foreword, Jean worries that in merely reading these conversations one misses Peter’s “occasional outbursts of laughter… his really impressive gravity… the intelligence which… showed through the language of his living person… a certain gusto, self-reliance, and all-weather quality which he showed plainly to us who saw him” (4). Yet, Peter’s precociousness is not fully lost as the conversations were transposed onto the page. One can clearly see a young Peter’s intellect, maturity, and curiosity shine through as he tells Jean, “the wise man knows he doesn’t know much. The more he knows, the more he knows there’s more to know” (81). As he was the inspiration for these manuscripts, one can imagine the kind of impression eleven-year-old Peter Esherick left on the writer turned philosopher Jean Toomer.

These conversations display a great sense of comfort and intimacy. Where Jean and Marjorie referred to Peter by the nickname Pete, he also does away with any formalities, calling this couple by their first names. Nini Almy, a neighbor and childhood friend of Peter recalls “a great shock” when—having come from a more traditional family than the Eshericks—she heard him call her “parents by their first names.” At eleven years old, Peter was at home in talking to two brilliant artists of the day. “Hasn’t Marjorie been taking notes?” he wants to confirm; and reading through these manuscripts one comes to understand that the idea for a book hatched in Peter’s brain: “well then, couldn’t we just take that and use it?” he asks, “we could put it into a book and sell it, not for the money but for the good of the country, and other people can hear what I’ve heard;” Jean responds affirmatively, telling Peter “we can and we will. We’ll make a book of it, and share these talks with people for whom they may have some meaning” (134).

Read more about Jean Toomer and Marjorie Content on our blog.

For visuals of Mill House we recommend this video from the Solebury Township Historical Society at the 35:30 minute mark! Notice the converted bank barn and the wonderful Esherick interior.

Explore the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Post written by Visitor Experience Coordinator, Ethan Snyder.

Toomer, Jean. “Talks with Peter.” 1937.

Credit: Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

March 2021