This month’s article was originally published in the Wharton Esherick Museum Quarterly from Spring 1993.

Wharton Esherick and Henry Varnum Poor were close friends for nearly 50 years. They were born the same year and they died in the same year (1887-1970). Each influenced and supported the other in their similar careers. Both were trained as painters but in 1920 moved into the decorative arts to augment their incomes — Esherick into wood, Poor into ceramics.

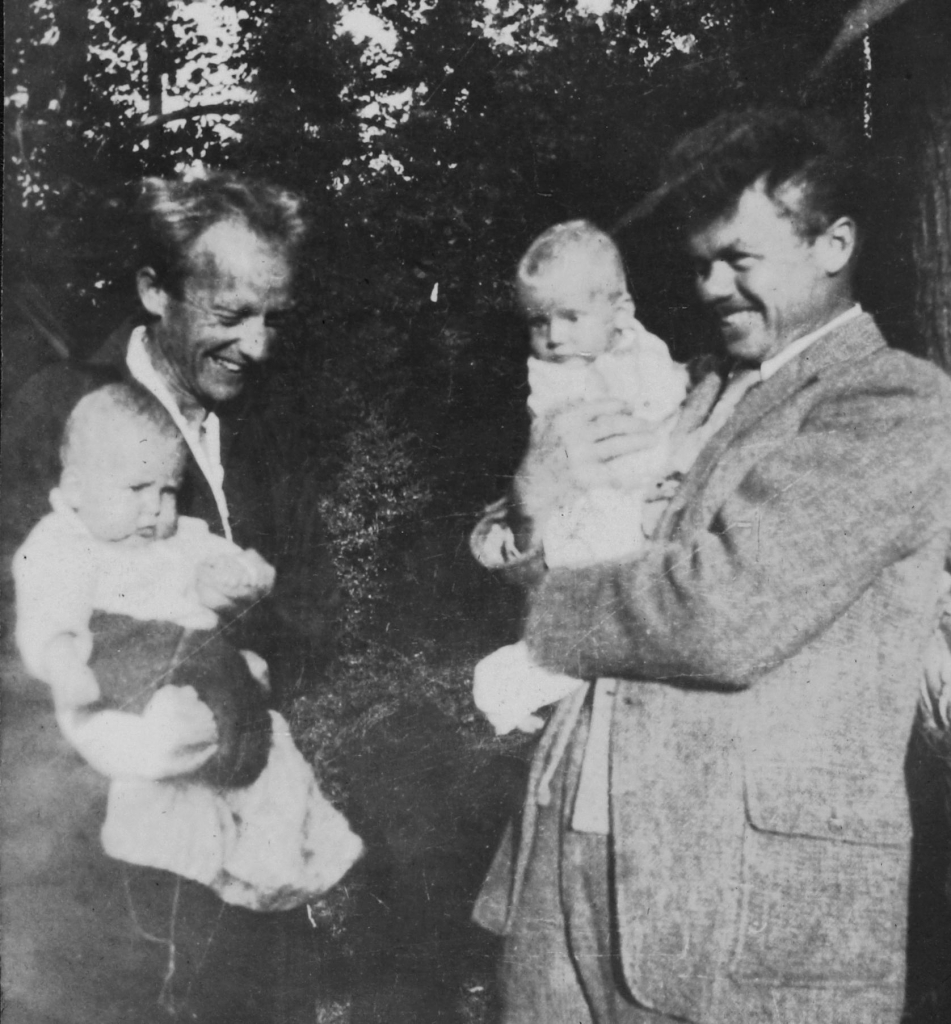

Recent research suggests that they met through the E. Weyhe Book Store which also served as a gallery for up-and-coming progressive artists. The bookstore had commissioned Poor to make decorative tiles for its storefront in 1923; Esherick began exhibiting there — paintings, woodcuts, a chess set — by 1925. Our knowledge of the two men’s earliest association was Marjorie Content’s recounting of being introduced by Poor to Esherick at a picnic on the banks of the Hudson River in the summer of 1926. Both artists had infant sons named Peter: Peter Esherick born in February, and Peter Poor in May. Both artists also had young daughters about the same age: Mary Esherick and Poor’s adopted daughter, Anne. Wharton and Henry both shared a rich sense of humor.

Though they had much in common that brought and kept them together, they had very different personalities. Esherick was raised and educated in Philadelphia and strayed no more than 25 miles to set up his household and studio. Esherick was determined from childhood to be an artist. Poor was raised on a Kansas farm and headed 1,500 miles west to study economics at Stanford University. In his junior year, he switched his major to art, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1910.

While Esherick was content to live a somewhat reclusive “organic” life in rural Pennsylvania, Poor, a more public person, preferred the big cities — San Francisco and New York — making contacts that would help his career. A talented painter, his work was selected for exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts as early as 1913.

After serving as “regimental artist” in an Army Engineer unit in France during World War I, he spent the spring of 1919 in Paris. Following a brief stay in San Francisco, he moved to New York where he soon met an influential dealer of books, prints and drawings, Mary Mowbray-Clark. At her suggestion, he moved to a well-established artist colony at New City, New York, on the west bank of the Hudson River just north of New York City.

Portrait plate of Wharton Esherick’s daughter Ruth by Henry Varnum Poor. Wharton Esherick Museum collection, not dated.

In 1920 he bought land there, built his home and studio “Crow House” and began making decorative ceramic tiles. By the mid-1920s he was creating plates decorated with still lifes, allegorical scenes, and portraits. Five such plates, including portraits of Wharton, Mary, and Ruth, hang in Wharton’s studio in the dining room and kitchen. A plate featuring Letty Esherick is also in the Museum’s collection.

Museum founder Bob Bascom traveled to Crow House many years ago to interview Anne and Peter Poor. Bob recalls that, “although the outside of the stone house seemed typical for its period, in the style of a picturesque French farmhouse, the interior surprised and shocked us. For here we saw elements that had surely influenced Esherick’s later work: a curving stone stair carried on an arch to an upper chamber with a side door halfway up; a stone fireplace too similar in design to the wood surround for the dining room fireplace in the Curtis Bok House to be coincidental; a slit of a window deeply recessed in the stone walls; floor levels a step up here, a step down there. Poor had built this house with his own hands, working with the local workmen, as Esherick did in remodeling his barn in 1921 and building the Studio in 1926.”

Crow House, Henry Varnum Poor’s studio in New City, New York. Photo: Friends of Crow House Facebook page, photo by Elizabeth Felicella.

Beyond the main room was a large studio added in 1931-32 with a wooden spiral stair that opens to an intermediate level halfway up, where it reverses direction. Probably influenced by Esherick’s 1930 spiral stair, it may have influenced his [Esherick’s] 1940 branch to the wooden wing. Perhaps these two had a game going, challenging each other in stairs, leapfrogging on each other’s ideas over the next several years as they built stairs for their respective clients. In 1935, when Esherick was building his spiral stair in the Bok House, Poor was building an equally unusual spiral stair in concrete for his neighbor, Maxwell Anderson.

Poor introduced Esherick to other artists in New City, including textile designer Ruth Reeves, for whom Poor had designed and built a house in 1922. The WEM collection contains one of her paintings, depicting the Esherick and Poor families at play together – the children in various stages of nudity, climbing trees, and swinging. Nudity was popular among artists at that time. Three tiles by Poor over the fireplace in the house he built for Maxwell Anderson show Poor at work fully clothed, while the Andersons sunbathe in the nude.

In 1928, Poor, Reeves and other decorative artists founded the American Designers’ Gallery in New York. Poor exhibited a bathroom decorated in his ceramic tiles, including a life-size nude in the shower, which brought commissions for three more. Esherick joined the group in the spring of 1929, but the gallery soon folded. Poor’s 1929 installation was “Elements of a Dining Alcove” with a new emphasis on wood, perhaps influenced by Esherick. The walls were vertical rough sawn yellow poplar boards of heart and sapwood. The dining table was of similar boards, supported by a pair of inverted, handsomely made, saw horses — the conceptualization of Esherick’s 1929 Flat-top Desk (also called the Sawhorse Desk).

At this stage, a major difference developed in their art. Esherick abandoned decorative, representational surface treatments as unnecessary “literature”, relying thereafter solely on form. Poor made the decision to continue the pictorial, explaining, “For lightness sake I like a storytelling design. Far from subtracting, it adds one more quality to the complex that makes up enjoyment. The storytelling and humor involved must be purely visual.” Another difference came with Esherick’s abandonment of painting early in the 1920s for sculpture, while Poor continued to paint throughout his career.

In 1932, the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired one of Poor’s paintings that had been exhibited earlier that year at the Museum of Modern Art. He was commissioned to create ceramic vases and lamp bases for the new Rockefeller Center — good enough to be stolen in the first few weeks. He was invited to join a gallery in New York that exhibited Edward Hopper, Reginald Marsh and other prominent painters of the time. He also painted portraits of his two friends: Theodore Dreiser and Wharton Esherick. The Dreiser portrait now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. and the Esherick portrait is part of the collection here at WEM.

Year after year, Poor won prizes and his paintings were purchased by museums around the country. He created frescoes and ceramic murals for public and private buildings and served on art commissions and juries. In 1946 he co-founded the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and invited Esherick to teach there.

Portrait of Wharton Esherick by Henry Varnum Poor, 1932. Oil on canvas, Wharton Esherick Museum collection

Unfortunately, efforts to preserve Crow House have struggled in recent years, with the building currently in a state of significant disrepair. You can learn more about Henry Varnum Poor, the preservation issues surrounding Crow House, and see numerous photos through the following resources: