On September 15, 2022, the Wharton Esherick Museum opened the third and final temporary installation of our 50th anniversary year celebration, Home as Stage. In addition to inviting four contemporary artists to use Esherick’s studio as their stage – you can read a blog post about their experiences here – WEM complemented these works with a selection of textile objects on loan from the Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM). These objects were produced by artists and architects whose careers overlapped with Esherick’s with compelling connections to the artist’s life, career, and experiences, including Viola Frey, Toshiko Takaezu, Lenore Tawney, and Robert Venturi. Their placement in Esherick’s Studio explores ideas around artistic networks and connections on an intimate, inviting stage.

Below, we’ll explore the connections between Esherick and Frey, Takaezu, Tawney, and Venturi. For more information on connections between WEM and FWM, please see our Spotlight Program on the same topic.

Lenore Tawney

Two works by the fiber artist Lenore Tawney – Cloud Pillow and Ear Pillow – are on view in Esherick’s bedroom. Tawney’s innovative approach to her medium shifted public perception about the artistic possibilities of textiles. Just as Esherick broke open the lines between furniture and sculpture, Tawney broke open notions of weaving and tapestry by experimenting with open-warp techniques and creating sculptural works, bringing fiber from the wall to three-dimensional space.

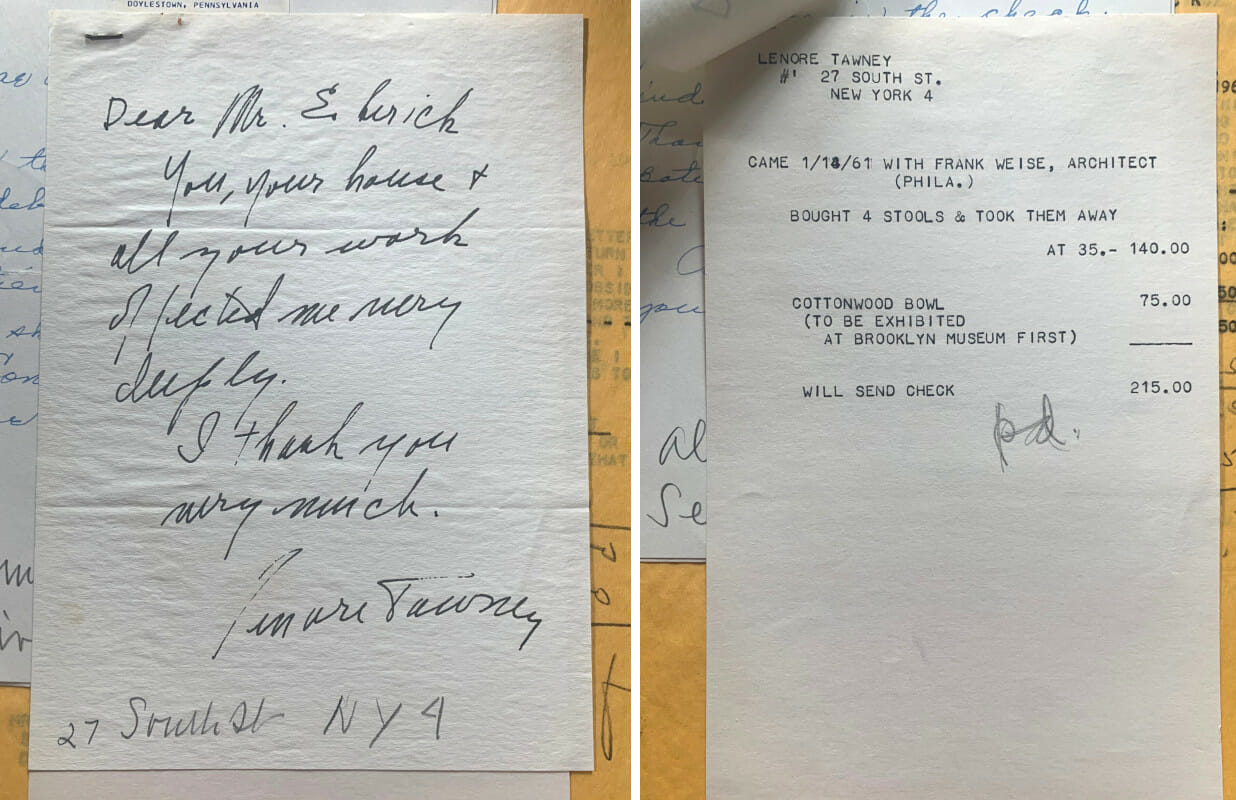

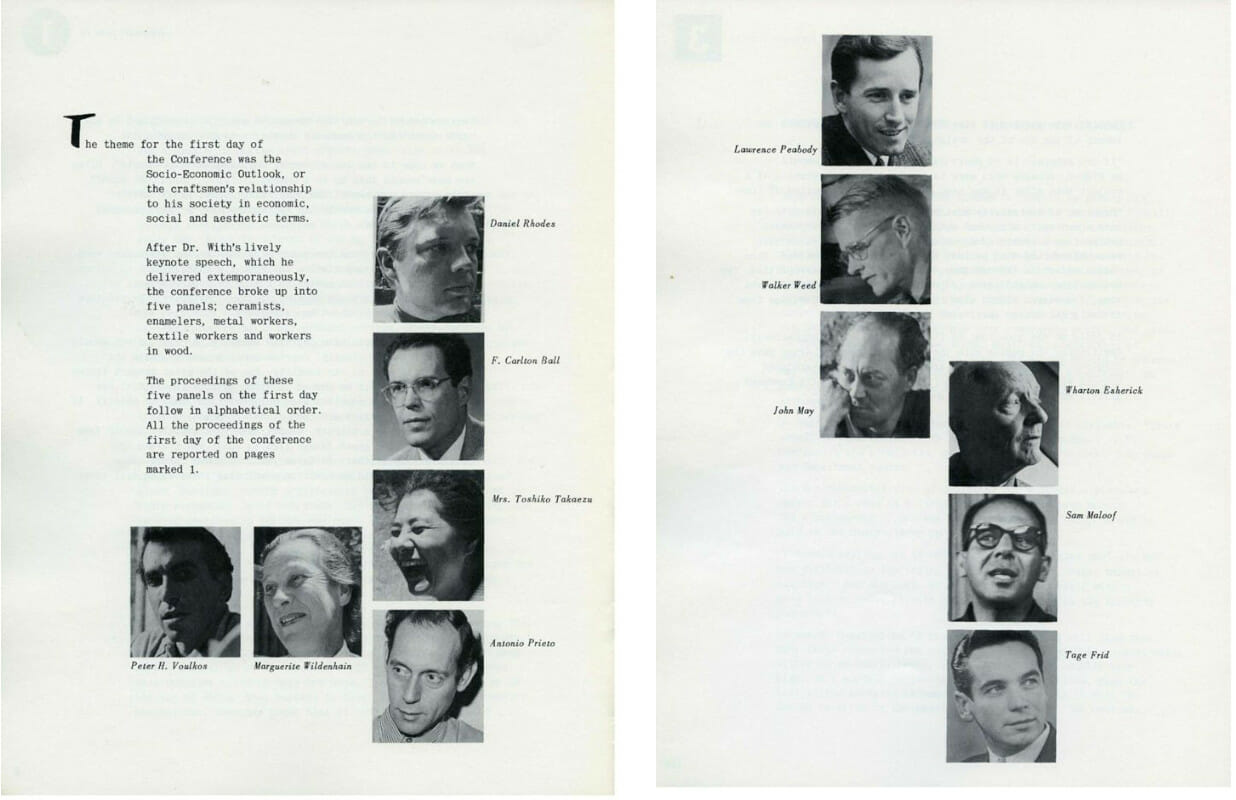

Tawney met Esherick in 1957 when the American Craft Council held its first national conference for craftspeople at Asilomar, on CA’s Monterey Peninsula. The two later exhibited together at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, where for the first time American crafts were a part of the United States Pavilion. Later, in 1961, Tawney visited Esherick’s home and studio with the Philadelphia architect Frank Weise. In a post-visit note that is part of WEM’s archives, Tawney writes that “You, your house, and all your work affected me very deeply.” Alongside that letter, we have a receipt for Tawney’s purchase of 4 stools and a bowl from Esherick, as well as a note mentioning that the bowl would go on display at the Brooklyn Museum in the exhibition Masters of Contemporary American Crafts (1961) before coming to Tawney’s studio. Tawney’s purchases from Esherick are now part of the artist-built environments’ collection at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, where Lenore Tawney’s entire estate went after she passed.

Lenore Tawney (1907-2007), Cloud Pillow, 1982, and Ear Pillow, 1982, Pigment on silk charmeuse, silk pongee. Collection of The Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo by Gordon Stillman.

Robert Venturi

Robert Venturi is often credited as the father of Postmodern architecture, especially through theoretical writing has been critical to the development and understanding of postmodern theory in architecture, from Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) to Learning from Las Vegas (1972), written in collaboration with his partner and wife Denise Scott Brown and their colleague Steven Izenour. Venturi’s motto “less is a bore” riffs off the famous dictum of the Modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (“less is more”). In turn, Venturi’s attitude seems in keeping with the proliferation of artwork and ephemera in Esherick’s home and studio.

This selection of napkins borrowed from the FWM for Home as Stage features a print, Grandmother (1983), which was developed at FWM. The design inspiration for Grandmother came from an old tablecloth belonging to the grandmother of an associate of Venturi and Scott Brown. They modified the tablecloth’s floral print and added an overlay pattern of dashes. Venturi has described the initial design idea by saying “We wanted a pattern . . . that was explicitly pretty in its soft, curvy configurations and sweet combinations of colors, and represented as well something with nice associations, those of flowers. By juxtaposing the two patterns, the dashes and the grandmother-tablecloth, we achieved design involving dramatic contrasts of scale, rhythm, color, and association, and one that is usable in many ways.” (VSBA Archives, project statement, July 19, 1990).

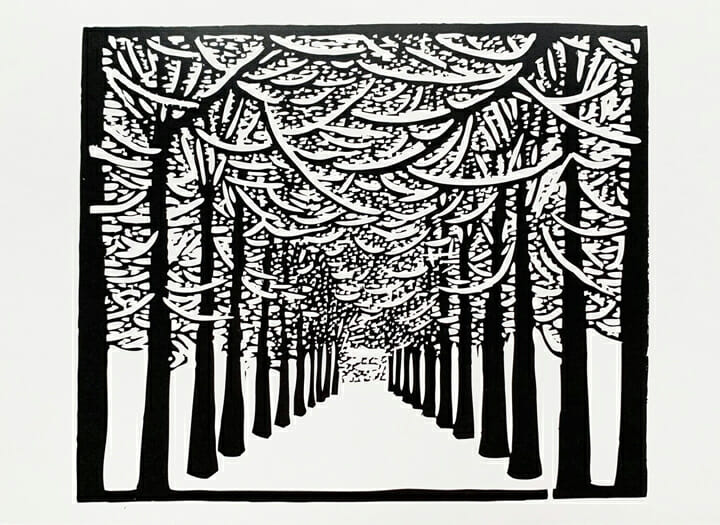

Venturi and his wife and partner Denise Scott Brown tested textiles not only at FWM, but also on the walls of their Chestnut Hill home, which has a compelling Esherick connection; an earlier owner was Helene Fischer, head of the Schutte-Koenig Company and one of Esherick’s most important patrons beginning in the late 1920s. Fischer commissioned some of Esherick’s best known works, including the S-K Chair (1942-44). The home that she and Venturi both resided in was depicted by Esherick in his well-known print The Lane (1931).

This is not Venturi’s only Esherick connection, however. Venturi worked for the architect Louis I. Kahn – Esherick’s collaborator in creating his purpose-built workshop – between 1956, when the workshop was finally realized, and 1958. Venturi and Kahn also both designed architecturally significant houses in Chestnut Hill in the early 1960s. Kahn’s Margaret Esherick House, for Wharton’s niece, features Esherick works in its interiors, while Venturi’s house for his mother Vanna is considered the first Postmodern residential building.

Robert Venturi, Grandmother (set of 4 napkins), 1983, Pigment on Cotton, Collection of The Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo by Gordon Stillman.

Wharton Esherick, The Lane, 1931, Woodcut. This building was home to both Venturi and Scott Brown and Esherick’s major patron Helene Fischer.

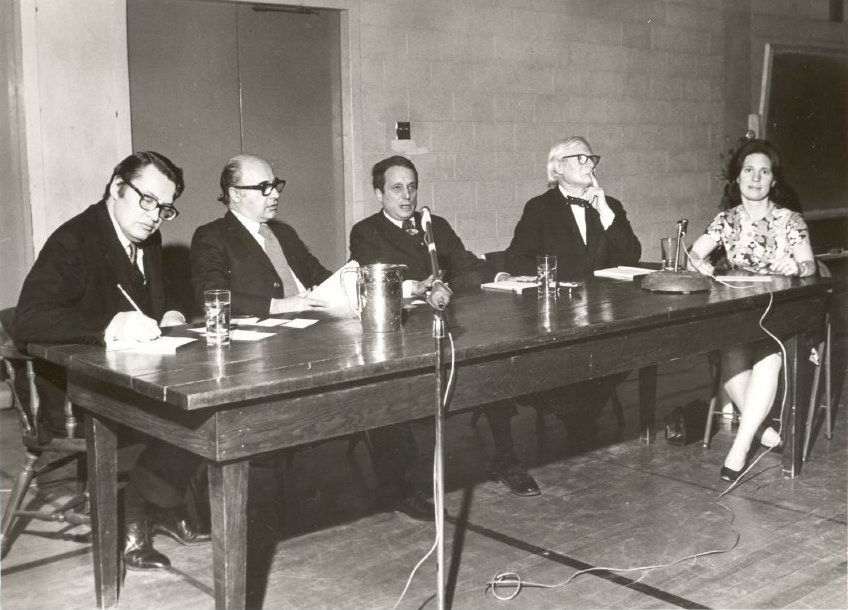

Venturi at the center of a panel discussion on architecture and the future of Chestnut Hill with others including Louis Kahn, second from right, organized by the Chestnut Hill Historical Society in 1967. Image Courtesy of the Chestnut Hill Conservancy.

Toshiko Takaezu

The ceramic artist Toshiko Takaezu and Esherick are conceptually connected through their interest in blurring the boundaries between function and sculpture. Takaezu is often credited with being the first artist to close the ceramic vessel as a way to explore ideas of functionality, all while conducting sensory explorations of material and form. Takaezu is well known for her moon pots, closed spherical vessels which often have hidden balls of clay inside them that rattle when moved. Takaezu’s sensory exploration of materiality and form reflects how engaging with Esherick’s work and studio is also a multi-sensory and highly tactile experience. At FWM, Takaezu worked to translate her moon pots into printed spherical textile forms. These are now on view in Esherick’s bedroom.

Esherick and Takaezu also had many collections in their personal and professional networks. Takaezu was a student at Cranbrook at Cranbrook Academy of Art where she studied under the ceramist Maija Grotell and weaver Marianne Strengell; one of Takaezu and Esherick’s shared close mutual friends, Jack Lenor Larsen, had also studied at Cranbrook under their teachers. Takaezu was also connected to the ceramist Henry Varnum Poor, Esherick’s friend for nearly 50 years. Takaezu and Esherick overlapped at Asilomar in 1957, where Takaezu was on the ceramics panel and Esherick served as an advisor to the wood panel. As early as 1955 they showed together at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery of Contemporary Art, and participated in numerous exhibitions alongside each other including The American Craftsman (1964) at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts.

Takaezu established her studio in Quakertown, New Jersey, in 1975 after teaching at various universities. Her work and teaching philosophy was grounded in the idea of blending art with life, seeing her home as not only a living space but also a studio and creative workplace. As at WEM, you can still visit Takaezu’s studio to learn more about the artist’s integrated approach to work and life.

Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011), Moon Balls, 1992, Pigment on Belgian linen, polyester stuffing. Collection of The Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo by Gordon Stillman.

Portraits of the Ceramics and Wood area panelists from the Asilomar Conference Program (1957) featuring Takaezu and Esherick.

Viola Frey

That notion of what a studio can mean and how it can represent an artist’s world is a major connection between Esherick and the artist Viola Frey. Frey and Esherick also had a similar trajectory in their initial approaches to their artistic studies and their eventual practice. Frey attended graduate school in Painting at Tulane University starting in 1955, where she studied with George Rickey and visiting artist, Mark Rothko. Just as Esherick left his own painting program at PAFA just shy of graduation so that he could pursue his own individual voice as an artist, so too did Frey. In 1957, rather than completing her MFA, Viola Frey moved to Port Chester, New York, to work at the experimental Clay Art Center with founder Katherine Choy. She began a gradual shift from painting, to painting on ceramics, to sculpture and three-dimensional form, which can be seen in this excellent online collection of her work over five decades.

Over the course of her career, Frey’s immense creative output developed a distinctive and personal iconography and palette, depicting human figures among objects of antiquity, flea market finds, and interior spaces. Frey thought of herself as a bricoleur – a junk accumulator – who found new meaning in juxtaposing objects to create new meaning. For Frey’s work at the FWM, she created wallpaper and textile patterns depicting human bodies alongside such objects, including Buddhas, Western figurines, and Pre-Colombian pots. Titled Artist’s Mind/Studio/World, this title and pattern provides an ideal summation of what a visit to Esherick’s space feels like – a trip inside his mind and world – as much as it reflects the importance of Frey’s own connection to the objects and spaces with which she built her creative practice.

Viola Frey (1933-2004), Artist’s Mind/Studio/World (pillows), 1992, Pigment on cotton, Collection of The Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo by Gordon Stillman.

Intrigued by these stories and connections? We invite you to come see Home as Stage at WEM through December 30, 2022, and to visit our archives to learn more about Esherick’s extensive networks and connections to other artists.

Post written by Emily Zilber, Director of Curatorial Affairs and Strategic Partnerships.

November 2022