A large number of Esherick works— over eighty objects in total— are set to leave the Studio for the first time in decades for The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick opening at the Brandywine Museum of Art in October and travel the country thereafter, first to Madison, Wisconsin and then to Cincinnati, Ohio. Believe it or not, some of these objects have never seen the world outside Esherick’s Studio walls. Thus, all these pieces are ripe to gain new stories as they journey to venues across the United States. We’ve been thinking a lot about how Esherick’s work used to travel during his lifetime and how, precisely, they made their journeys as we’re preparing for these objects to begin traveling this fall.

Drop Leaf Desk crated and getting loaded on moving truck to Brandywine Museum of Art, 2024.

Drop Leaf Desk crated and getting loaded on moving truck to Brandywine Museum of Art, 2024.

To piece together the different ways Esherick’s work traveled during his lifetime, we dug into archival materials relating to some of his most well-documented exhibitions between the 1930s and 1960s, and some records relating to Esherick’s furniture business in the 1950s and 1960s. While shipping receipts, invoices, and correspondence about shipments might seem mundane, locating this documentation while actively preparing to send Esherick’s work out today was quite thrilling! Sending objects to clients or for exhibition could be a logistic feat depending on the length and mode of travel, as well as how quickly a work might need to be received for installation at a show.

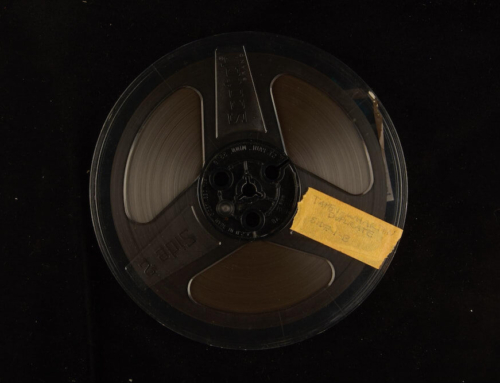

Shipment inventory for works going to Museum of Contemporary Craft, 1958.

Shipment inventory for works going to Museum of Contemporary Craft, 1958.

New York City

We’ll begin with a place where Esherick’s work traveled quite frequently: New York City. When Esherick needed to get his work up to the city, whether it was for the World’s Fair in 1940, his solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in 1958, or the Brooklyn Museum in 1961, shipping appeared to be relatively easy. Esherick’s work generally traveled up the I-95 corridor on a truck. As we see from this 1958 shipping inventory for the over three-dozen pieces sent to New York for Esherick’s solo show, Quaker Storage Company was hired to make the shipment. They appear to have contracted their truck from United Van Lines to drive pieces up the highway corridor.

Esherick’s home was, and still can be, relatively difficult to find, so it makes sense that one of these shipping receipts retains instructions to movers for reaching the Studio. You have to wonder how useful Esherick’s instructions were, because they don’t appear to be the clearest:

“EXPRESSWAY, VALLEY FORGE ON RT. 23 WEST TOWARD VALLEY FORGE, FIVE MILES WEST OF VALLEY FORGE ON 23 SIGN. COUNTRY CLUB ROAD LEFT ON COUNTRY CLUB ROAD SIGN PAOLI FIVE MILES GO TWO MILES TO TOP OF HILL. U.S. ARMY ROAD IN THAT ROAD ONE BLOCK SIGN ON RIGHT.”

Once the moving truck reached Esherick’s hillside home and his pieces packed up to travel to the MCC, Esherick jovially wrote to Robert Laurer to let him know the truck was on its way: “the truck has gone with all the load of trash!”

How did Esherick pack his pieces for transport? For their trip to New York City, his pieces were packed into a crate. A packing document from 1958 gives us a glimpse into what pieces were packed together to be bedfellows for the journey. For example, one box contained six items including trays, bowls, platters, plus a chess set. Another crate contained a number of kitchen items, as well as a bird sculpture, a piece of First Born (1927), and 14 small pieces required for assembling the Studio’s Spiral Staircase.

We know well in this age of online shopping that shipping can be pricey. While Esherick generally had to front the cost himself for packing supplies and shipping his work, he would eventually be reimbursed by whatever institution he was sending his work to. For his solo show, Esherick invoiced the Museum of Contemporary Crafts a total of $500. The invoice contains charges for time taken to make phone calls, the transit of objects to New York City, as well as for the time it took to dismantle and prepare the Spiral Staircase for shipment.

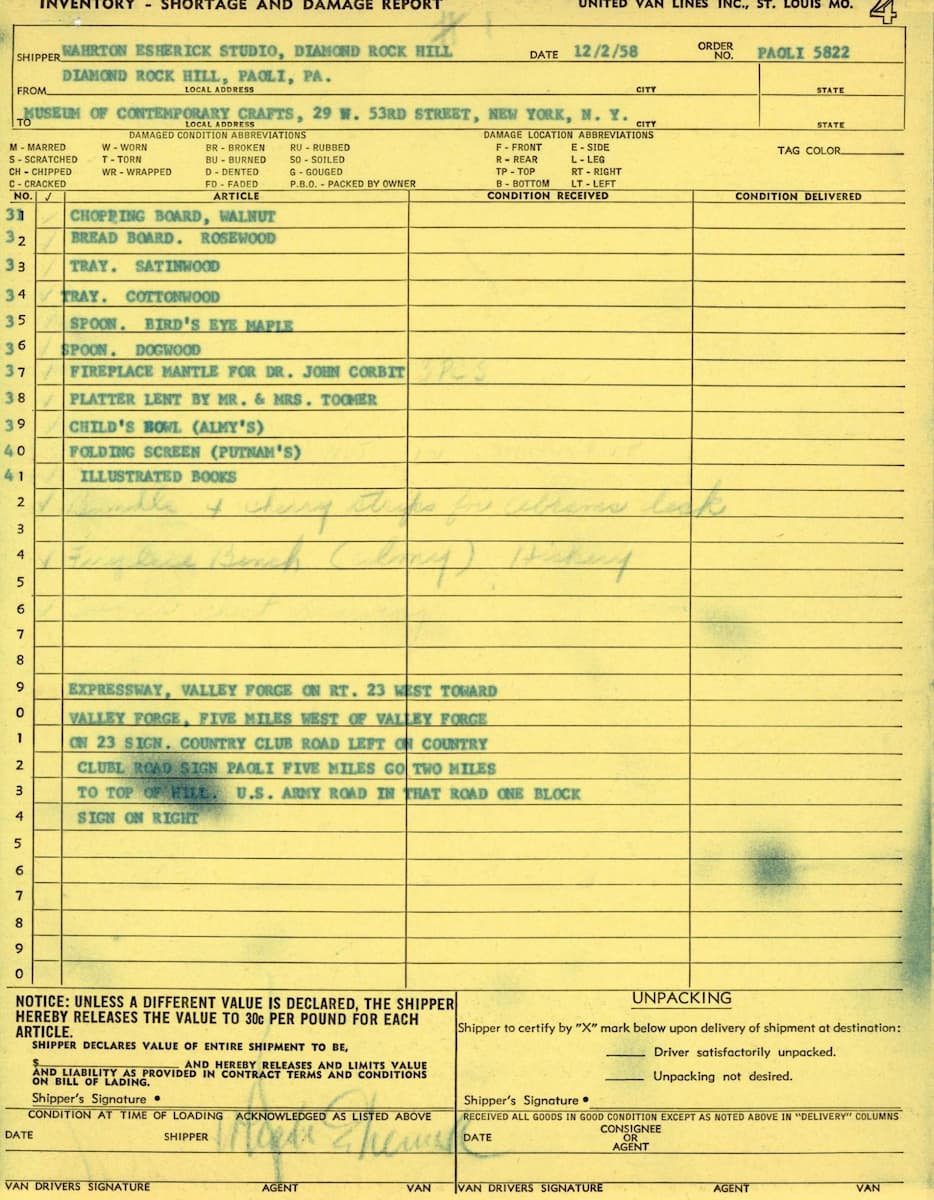

Shipping receipt for railway transportation of Esherick’s work to San Francisco, 1938.

Shipping receipt for railway transportation of Esherick’s work to San Francisco, 1938.

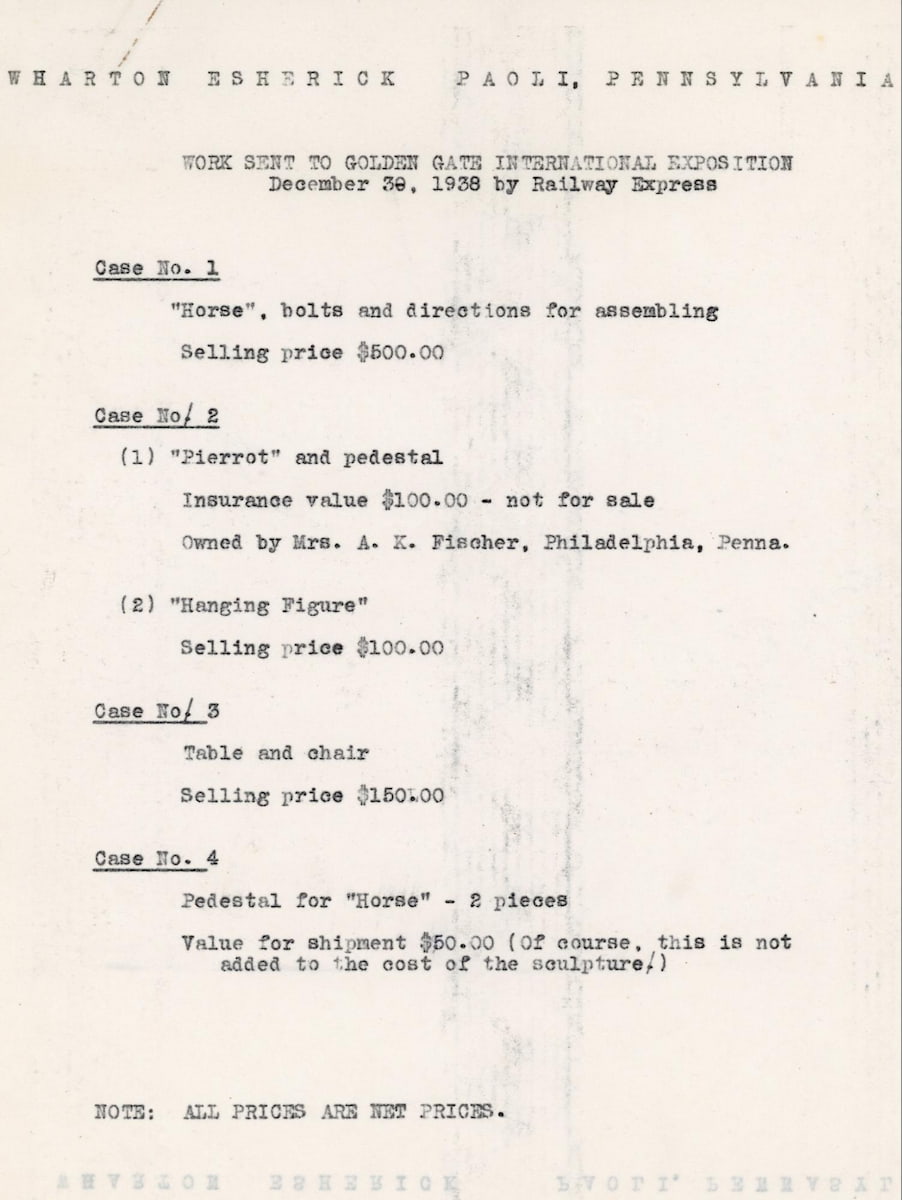

Crossing the Country to San Francisco

When it came to shipping his pieces further afield, such as to the San Francisco Golden Gate Exposition in 1938, Esherick had to utilize other modes of transport. Sending his work across the country by truck or van would have not only taken too long, but pieces would be in transit too long to ensure their safety. Thus, as we see from this extant shipping receipt, the work Esherick sent across the country— including the sculpture Pierrot (1931), the large horse Cheeter (1934), a hickory table and chairs (1938), as well as the Hanging Figure (1928) that serves as the counterweight to the Studio’s trapdoor in the bedroom—traveled by train! To make shipping this work across the country a bit easier, the organizer of the Fair’s Decorative Arts Division, Dorothy Liebes, sent Esherick a prepaid shipping label. As we see from the shipping receipt, the four crates of work weighing a total of 827 pounds were shipped out to San Francisco via the Railway Express Agency on December 30, 1938.

Esherick’s packing checklist for content of crates shipping to San Francisco, 1938.

Esherick’s packing checklist for content of crates shipping to San Francisco, 1938.

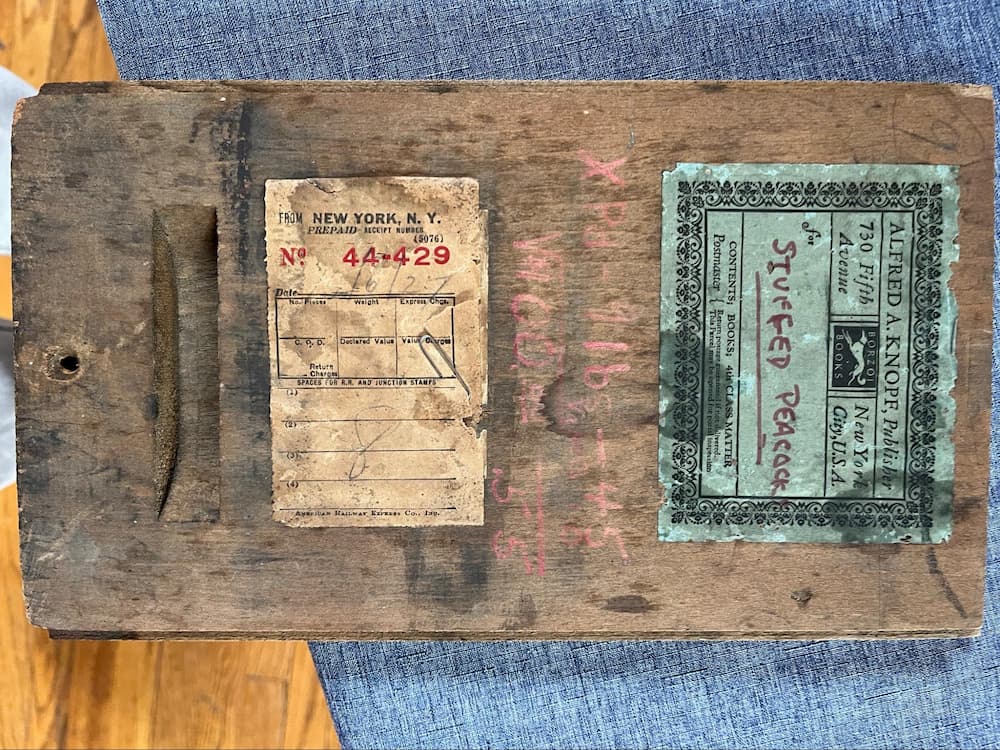

While we do not have any extant shipping crates from these exhibition in our collections, our site is home to a small and unassuming, yet informative shipping crate that originated from a package of woodblock and engravings sent to the publisher Alfred Knopf to illustrate Emily Clarke’s 1927 book Stuffed Peacocks. The machine-made finger jointed box is stuffed with newspapers that wrap Esherick’s blocks and engravings. The labels affixed to the box have indeed seen better days. However, we can learn from the label’s remnants that this shipment of blocks and engravings were also shipped via the American Railway Express that took Esherick’s work across the country in the following decade. Just like for the Golden Gate Exposition, this package was prepaid. Labels specify that the package weighed a total of nine pounds and was sent to New York City on the Pennsylvania Express via the Pennsylvania Railroad. Each block or engraving is wrapped and nestled in enough newspapers to keep the blocks from moving during transit. It’s curious that the blocks were never unpacked upon their return to the hillside. However, this untouched box suggests that the printmaking materials were packed well enough that this shipping crate would serve as good enough storage. Sometimes pieces didn’t make it to their destination, back to their owner, or even back to the hillside in one piece, but insurance and repair is a whole other story!

Shipping crate for woodblock and engravings sent to Alfred Knopf for Stuffed Peacocks, 1927.

Shipping crate for woodblock and engravings sent to Alfred Knopf for Stuffed Peacocks, 1927.

Going Overseas!

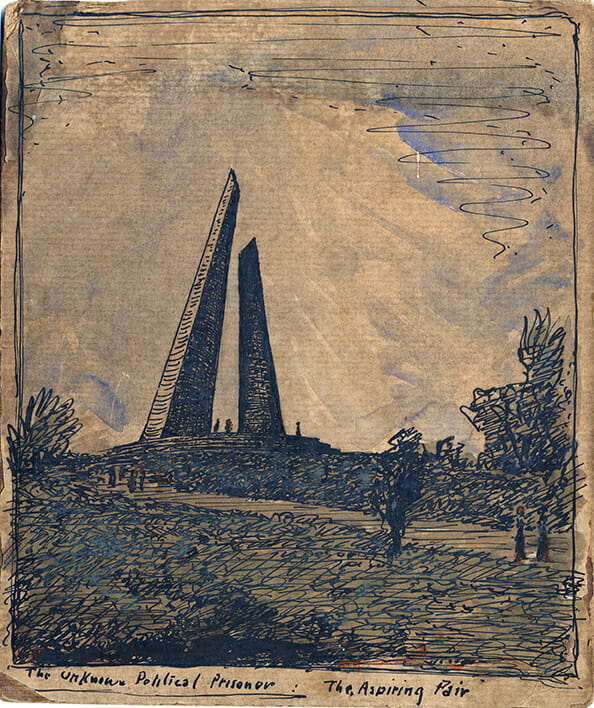

Esherick’s work has also landed overseas. Work was sent to Europe for exhibition twice during the artist’s lifetime, and he also occasionally had to ship work overseas to patrons in other countries. In 1952, Esherick’s maquette Aspiring Pair was juried into an international exhibition in London. The maquette was a speculative piece for a monumental work that was never realized at full scale. This competition was organized in conjunction with the Museum of Modern art and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, with the winning submissions being exhibited at the Tate Gallery. In 1958, Esherick also sent samples of his work overseas to the World’s Fair in Brussels, Belgium. Two bowls, a pair of salad servers, and a music stand were accepted into the Fair by an American jury organized in conjunction with the American Craftsmen’s Council in NYC and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

Speculative sketch for full scale version of Aspiring Pair, 1952.

Speculative sketch for full scale version of Aspiring Pair, 1952.

Because shipping packages overseas is not always easy or cheap, the American institutions involved in these exhibits helped a great deal in getting work to Europe. Both of these shows required work to be juried in, so Esherick only had to send his work to the organizing committees in New York or Boston, who after jurying Esherick’s work in, took care of getting his work across the Atlantic. However, how did the organizing committees send Esherick’s work to Europe?

Documentation related to the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958 can help us begin to answer this question. The jurying took place at the Craftsmen’s Council’s headquarters on New York’s upper west side. Once it was juried in, the institution should have sent Esherick’s the necessary paperwork like loan agreements and insurance policies before proceeding any further. As the ACC’s president, Eileen Osborne Webb wrote to Esherick in January 1958, he would soon be receiving paperwork from the staff at ICA Boston that needed to be completed for their records. However, correctly assuming Esherick’s excitement about showing in another World’s Fair, the institution jumped the gun and asked Esherick for forgiveness for sending it overseas rather than his permission. Webb assured the ICA Boston that sending Esherick’s work to Europe would be agreeable and they could ask for permission after the fact. Thus, as Webb wrote to Esherick in the same letter, “ordinarily, such a letter comes before things are requested,” however they have “assured [the ICA Boston] that sending your work to Brussels would be agreeable to you. I certainly hope this is true as it is already packed and may even be on the high seas.”

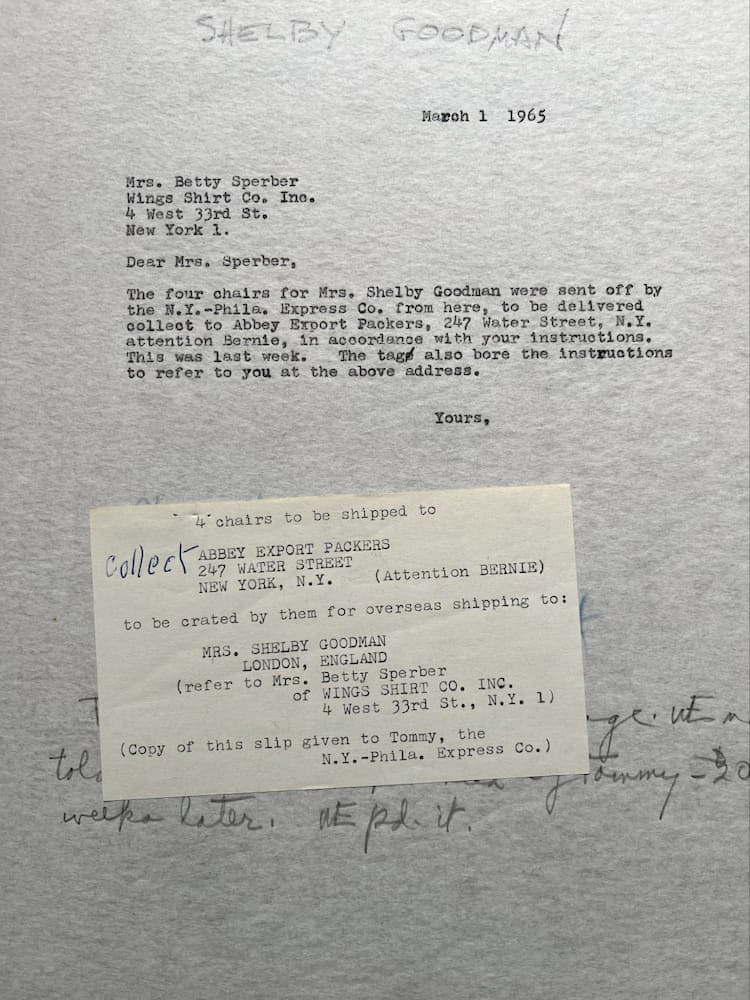

Correspondence and shipping receipt for repaired chairs sent to London, 1965.

Correspondence and shipping receipt for repaired chairs sent to London, 1965.

We can find out more details about how work was shipped overseas when we look toward the accounts of Esherick’s individual private clients. A series of correspondence dating to 1965 pertains to the shipment of four chairs Esherick repaired for a client who had moved to London in recent years. The chairs had been purchased years before and the client had brought them to New York on her last visit stateside in the hopes Esherick would be able to make the repair. Someone writing on behalf of Esherick’s client who was based in New York City requested that he send the four chairs back up to the city to a shipping company who specialized in overseas shipping to England, called Abbey Export Packers. Esherick shipped the chairs to this export company with the New York–Philadelphia Express Company. Once the chairs were received, Abbey Export Packers crated the chairs for their voyage overseas.

Oblivion in the process of being crated, 2024.

Oblivion in the process of being crated, 2024.

Shipping out work during his lifetime was part and parcel of Esherick’s practice. Packing and shipping furniture and sculpture was part of the mundane routines that making artwork entailed. Considering that today these pieces are part of a museum collection and no longer an artist’s personal property, we treat, pack, and ship in a radically different way. No longer does Esherick’s work board a train to cross the country or take a boat to cross the Atlantic. Luckily, there’s a whole specialized industry for packing, moving, and shipping art that utilizes the latest technologies to ensure the safety of objects throughout their journeys.

Post written by Ethan Snyder, Public Programs & Collections Manager

September 2024