Usually, our Woodcut Wednesday posts on our Facebook page consist of just a few sentences about one of the over 350 woodcut prints Esherick created during his career. However, every so often, a print has a story worth more than a few sentences – and today’s print led our staff on an amazing research treasure hunt!

The featured print this week is of a lovely prismatic peacock used as the dust cover art for the 1927 publication Stuffed Peacocks written by Emily Clark and published by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, for which Wharton produced nine woodcuts.

The featured print this week is of a lovely prismatic peacock used as the dust cover art for the 1927 publication Stuffed Peacocks written by Emily Clark and published by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, for which Wharton produced nine woodcuts.

Emily Clark (1890-1953) is best known as a writer and founding editor of Richmond, Virginia’s The Reviewer, a literary magazine that played a major role in the Southern Renaissance (1920s – 1930s). Prior to the Renaissance, southern writers tended toward themes that romanticized and glorified the Antebellum South. However, the Renaissance moved writers to themes about race, gender, identity and the burden of history in the South; themes that are still relevant today. Some of the best known Southern Renaissance authors include William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, Tennessee Williams and H.L. Menken who was a precursor to the movement. Many works by these writers line the bookshelves in Wharton’s bedroom here at the Studio. This literary movement continued to inspire 20th-century writers after it’s height in the 1920s. Perhaps the best-known work inspired by the Southern Renaissance was Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1961.

It is not known exactly how Emily Clark met Wharton Esherick, or if they met at all. Wharton could have been hired as an illustrator through her publisher, but there is a very good chance the two met through the Centaur Book Shop when she moved with her new husband to Philadelphia in 1924. The Centaur Book Shop produced a total of three publications with Esherick illustrations with woodcuts including, Song of the Broad Axe in 1924, Yokahama Garlands in 1926, and The Song of Solomon in 1927. Wharton spent a lot of time there; it was a favored meeting place of Avant Garde writers of the time and would have certainly attracted Emily Clark. You can read more about the Centaur Shop (and press) from a past post here.

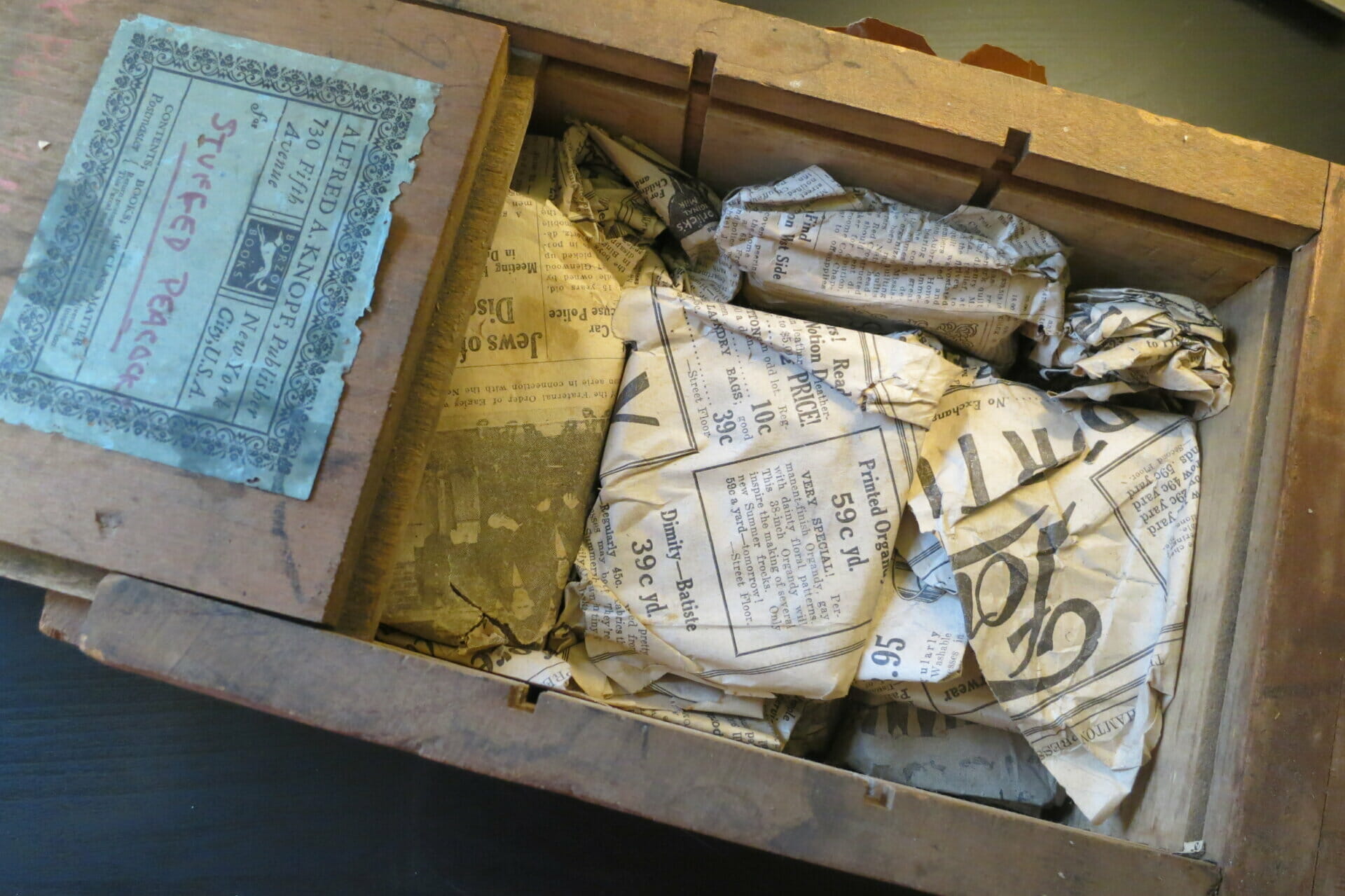

In the collection at the Museum, we have eight of the original nine blocks Wharton carved for Stuffed Peacocks. Ironically, the block we do not have is the one that inspired this post! After admiring the print of the peacock, we decided to check out the blocks themselves. When we pulled them from their storage space, we found they were kept in a solid wooden box, screwed shut and stored in a separate location from the other 300+ woodblocks in our collection.

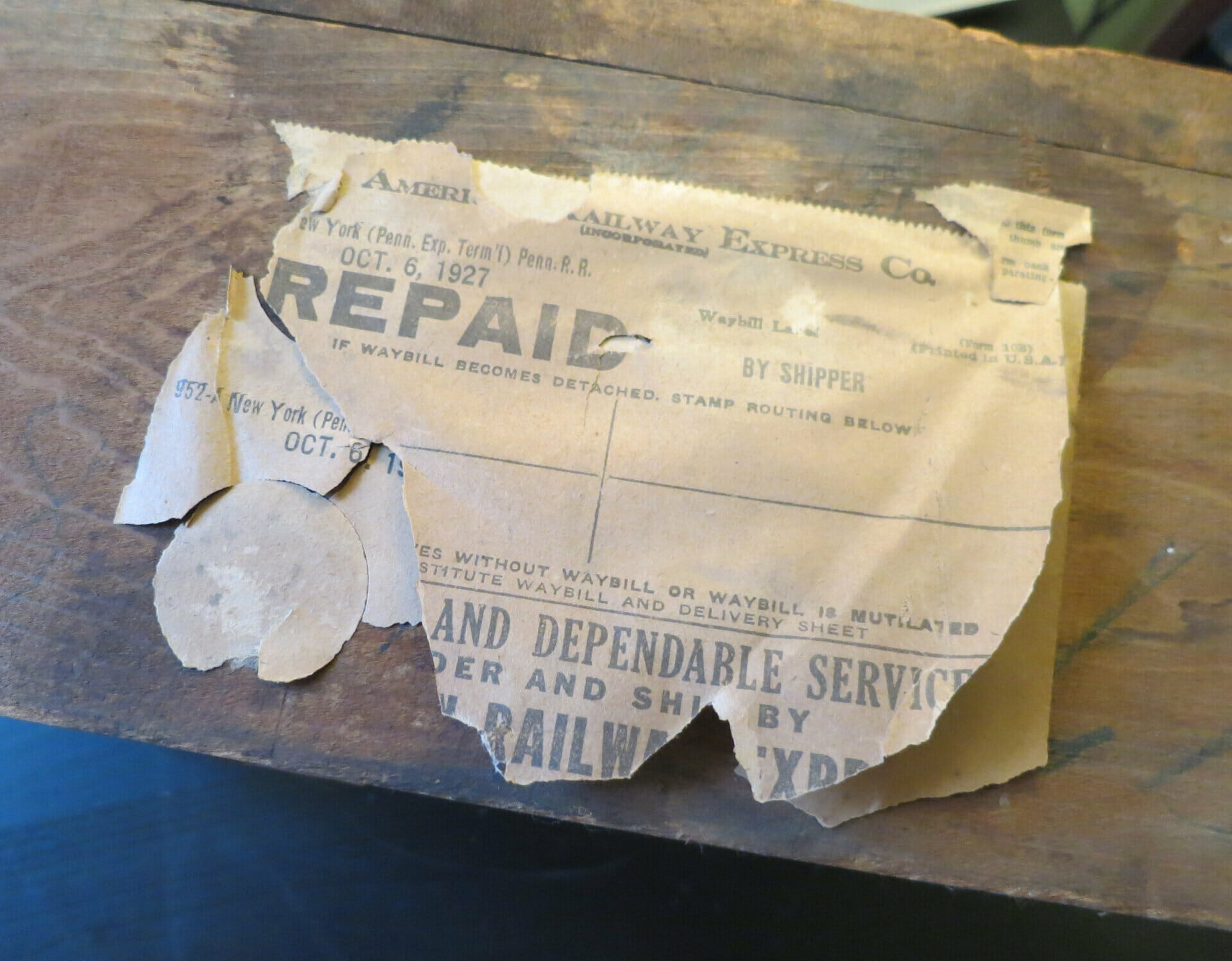

American Railway Express shipping label.

The box holding the blocks measures 13″ long, 8″ wide and 6″ high and is joined at the corners with finger joints. Pasted to the side of the box is the original shipping label from the American Railway Express Company dated October 6, 1927. Though the label has seen better days, we could still make out who the shipping company was, that the package was prepaid, when the box was shipped and that it was headed for New York on the Pennsylvania Express, Terminal 1 via the Pennsylvania Rail Road. On the top of the box is a green address label for “Alfred A. Knopf, Publisher, 730 Fifth Ave. New York City, USA” noting that the contents were “for Stuffed Peacocks”.

The blocks for “Stuffed Peacocks”, wrapped in newspaper and packed tightly for shipping.

Opening the box was even more exciting than discovering the labels on the exterior. Inside we found a stack of folded newspapers from 1927 used to fill the space between the top of the box and the eight woodblocks below. Each block is wrapped in a section of the same newspaper and wedged in tightly so they wouldn’t shift during shipping. There were even a few wadded up sections of newspaper stuffed in around the blocks. Judging by how we found the blocks, it’s quite possible that Wharton received them back from the publisher and decided that the blocks were wrapped up safe, and so he kept them in the box and stored it away.

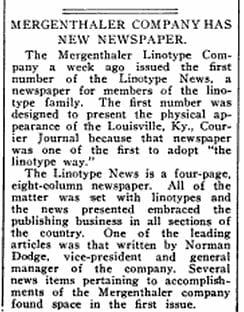

The treasure hunt continued when we started to read the newspapers. The papers were each the same: Volume VI of The Linotype News, a publication of the Mergenthaler Linotype Company which was founded by Ottmar Mergenthaler, inventor of the linotype printing process. The publication focused its articles on the publishing business all across the United States. A small section on the front page boasts: “As usual, this issue of The Linotype News has been composed entirely on the Linotype. The news and feature heads are Linotype set. So is the news and feature body matter. Likewise the rules, borders, dashes and other ornaments. A complete listing of the faces used appears on page four.”

Clipping announcing The Linotype Newspaper in the Fourth Estate: A Newspaper for the Makers of Newspapers

The Linotype News highlighted what different printing companies were doing, how they were using and improving the linotype process as well as other articles of note to the printing community. Making the front page headline of this volume: “Lino on N.E.A. Speical Train Comes Thru With Flying Colors”, an in-depth look at a traveling print shop inside the baggage car of the National Editorial Association’s special train through Nebraska and the Black Hills as part of their Omaha convention.

So you can see how a simple Woodcut Wednesday post on our Facebook page called for a deeper exploration and more than a few sentences about one of the prints from a book Esherick illustrated. As we often find when researching Esherick and his life, you never know what fascinating rabbit trails it will take you down!

Post written by WEM Curator & Program Director, Laura Heemer.

Block from “Stuffed Peacocks” with its newspaper wrapping.