One Object, Many Stories: Esherick’s Music Stand is currently on view in the Visitor Center. This installation offers a deep dive into one of Esherick’s most well known sculptural furniture forms. The display explores this iconic object through many lenses, from Esherick’s friendship with Rose Rubinson – who, along with her husband Nathan (Nat), commissioned Esherick’s first music stand and were among his most significant patrons — to the music stand’s context on an international stage. It also shares how the music stand inspired new designs for Esherick and its ongoing influence with the next generation of makers.

Guests to the Museum are able to view the prototype music stand – the very one created for Rose Rubinson – along with a selection of drawings and archival materials that further illuminate these stories. However, the materials WEM has in its archives and community that explore the Music Stand and Esherick’s relationship with the Rubinsons are much deeper than what the space available in our Visitor Center – formerly Esherick’s one-car garage – can hold. We are excited to share a few additional items here that didn’t make it into the display case!

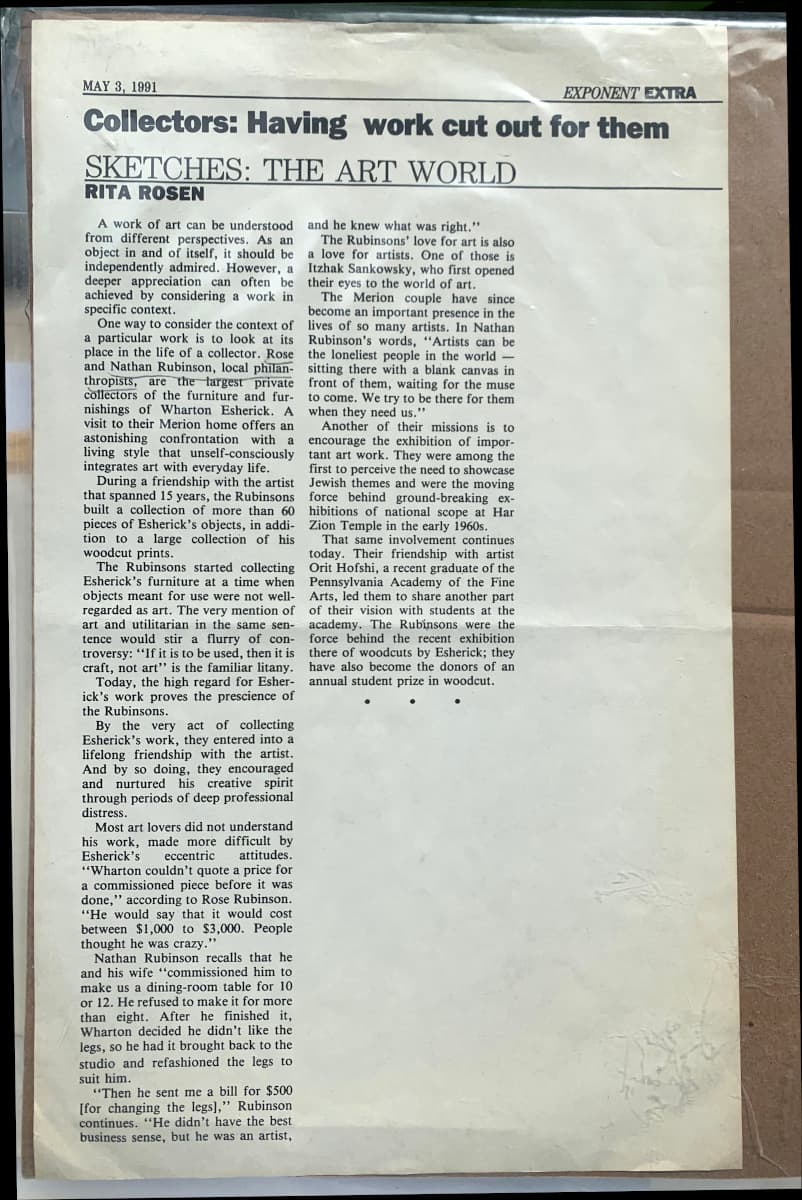

The prototype music stand is now a promised gift to the WEM collection through the generosity of Geoffrey Berwind, the grandson of Nat and Rose Rubinson. Geoffrey is also a member of the Museum’s Board of Directors, continuing the legacy of support and involvement with the museum started by his grandparents. This newspaper clipping from Geoffrey’s personal collection illustrates the invaluable role the Rubinsons played both during Esherick’s own lifetime and beyond.

The article comes from the Exponent Extra (May 3, 1991), published just weeks after the close of an exhibition of woodblock prints from the Rubinson’s collection at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). The article provides an overview of the Rubinson’s relationship with Esherick both as clients and friends, and a broader look at the visionary role the Rubinsons held as patrons and supporters of the arts. This includes their involvement with exhibitions at Har Zion Temple in Penn Valley in the 1960s – WEM’s archives include drawings for an Esherick project at Har Zion which was never realized – and the establishment of the Rose and Nathan Rubinson Award in Memory of Wharton Esherick at PAFA, which recognizes students of excellence working in woodcut prints and continues to be awarded each spring. The article is rich with quotes from Nat and Rose that illuminate their philosophy as collectors and their encouragement of Esherick in particular.

“Wharton couldn’t quote a price for a commissioned piece before it was done,” according to Rose Rubinson. “He would say that it would cost between $1,000 to $3,000. People thought he was crazy.”

In Nathan Rubinson’s words, “Artists can be the loneliest people in the world – sitting there with a blank canvas in front of them, waiting for the muse to come. We try to be there for them when they need us.”

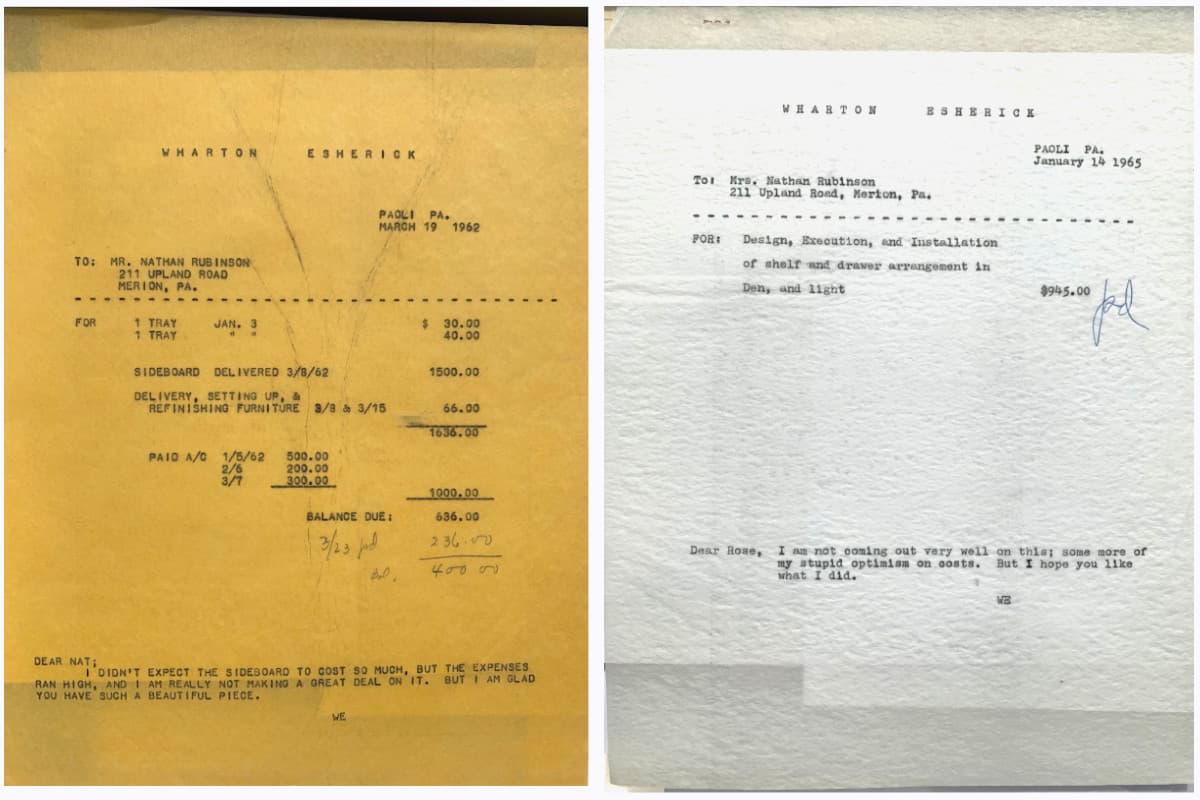

Two bills from the WEM archives further reflect the difficulty Esherick faced in estimating the final costs of his commissioned works – a negotiation with which he never seems to be completely at home. These invoices also show us the close nature of his friendship with the Rubinsons. On each document, Esherick shares with Nat and Rose a candid note on the final cost. One is tinged with regret that he must charge more than expected, and the other with some grief that he’s not charging as much as he should. It’s also clear from each note that the Rubinsons’ enjoyment of the work and its place in their home was meaningful for Esherick.

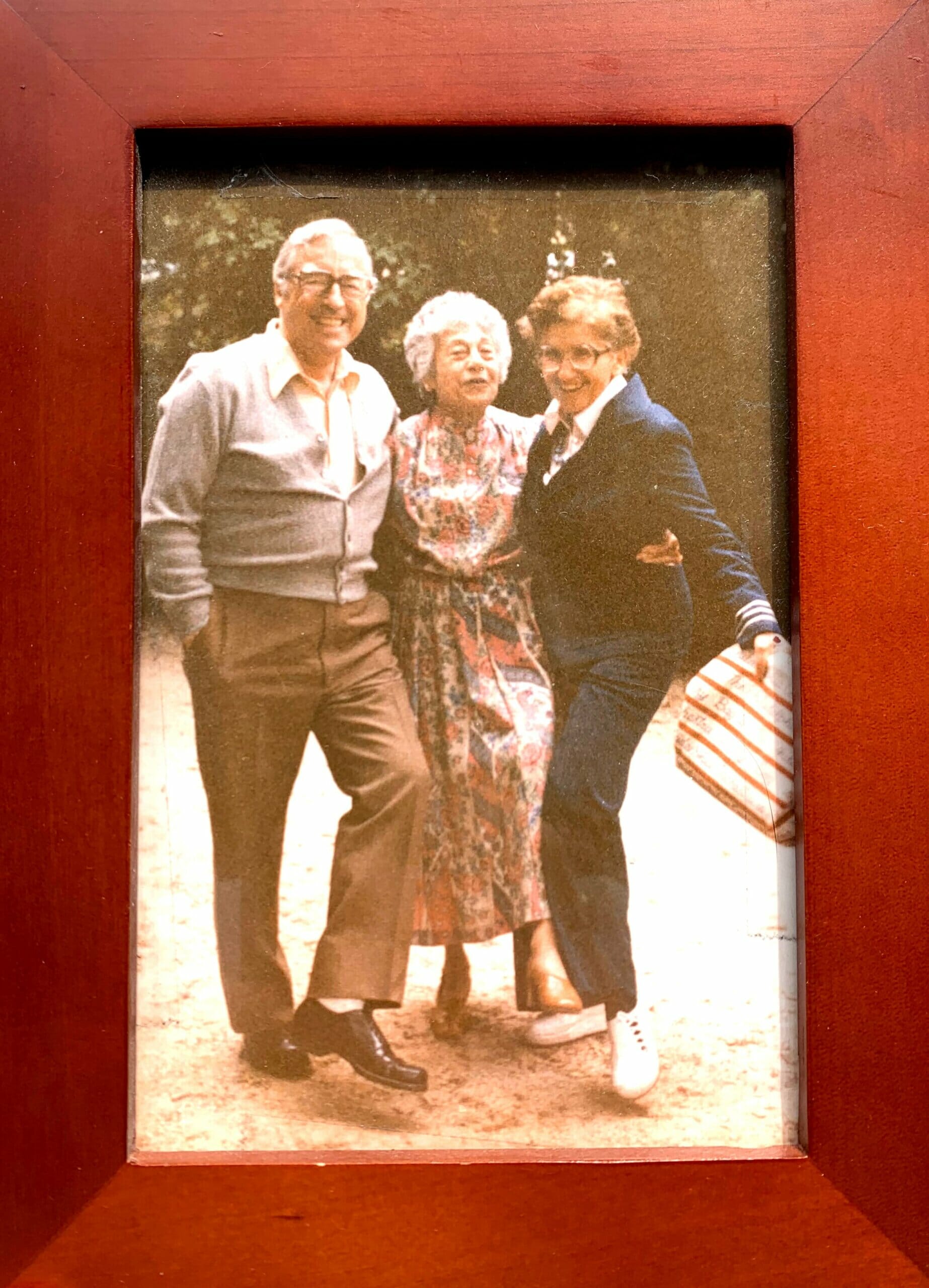

Nat Rubinson (left), Miriam Phillips (center), and Rose Rubinson (right) kicking up their heels – Photo from Geoffrey Berwind’s personal collection.

The Rubinsons continued to support and celebrate Esherick’s legacy after his passing and the Studio was opened to the public as the Wharton Esherick Museum, including Nat’s role as a founding member of the WEM Board. This photo of Nat and Rose with Miriam Phillips, who was both Esherick’s partner in the latter half of his life and the museum’s first curator, perfectly captures the vitality with which they took on the role of stewarding Esherick’s legacy. Their joyful spirit and enthusiasm for the arts is one that – we are grateful to say – their grandson Geoffrey Berwind continues to honor here at the museum.

Explore the exhibition, One Object Many Stories: Esherick’s Music Stand

View the Spotlight Talk: Geoffrey Berwind and Esherick’s Music Stand

Learn more about the WEM archives

Post written by Katie Wynne, Deputy Director of Operations and Public Engagement

March 2023