Left – Reverence, Wharton Esherick’s first design for Sherwood Anderson’s grave marker; Right- Esherick’s alternate design chosen by Anderson’s widow.

Sherwood Anderson (left) with neighbor Felix Sullivan (right), the inspiration for Esherick’s wood sculpture, Reverence.

Wharton Esherick and Sherwood Anderson met in Fairhope, Alabama in 1920, striking up what would be a lifelong friendship. Anderson, the author of such notable works as Winesburg, Ohio, came to settle just outside of Marion in Troutdale, Virginia, living in the countryside in a large stone house he called “Ripshin.” Despite the distance, the two remained close. Wharton made multiple visits to Ripshin, sometimes staying long enough to help edit Sherwood’s work, or carve sculptures from the Virginia white pine, as he did for his 1934 sculptures, Spiral Pole and Buck. Wharton reminisced about his visits to see Sherwood in letters to other friends, stating, “he lived like a country gentleman, works alone in his cabin in the woods in the morning; wanders over the hills in the afternoon, talking crops or cattle with his man.”

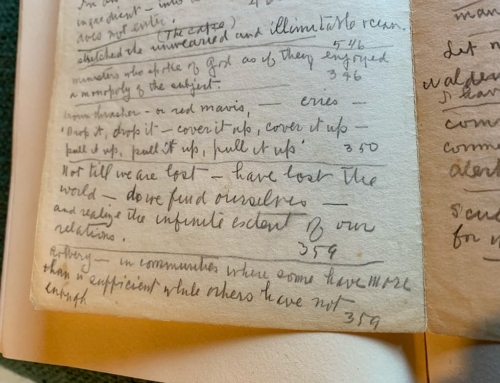

Prior to his death in 1941, Sherwood requested that Wharton design his grave marker, a powerful testament to their friendship and mutual admiration. Wharton created Reverence, a 12-foot tall creosoted black walnut figure. Wharton had acquired the log from his friend and wood supplier Ed Ray, an exceptional log, 36 inches in diameter and free of knots. For the piece Wharton drew inspiration from Anderson’s sorrowful neighbor, Felix Sullivan, who he observed at Anderson’s gravesite, leaning on his staff.

A towering monument of a figure represented in deep broad planes, Reverence would become a celebrated sculpture of Wharton’s, but it was not used as Sherwood’s grave marker. Thinking practically, Sherwood’s widow, Eleanor Anderson, worried about the tall wood piece being susceptible to vandalism, and that it would not last long in outdoor conditions. Wharton returned to the drawing board, developing a gentle curving abstract form, the model for which now sits in his Studio’s south window. This was one of three models Wharton presented to Eleanor, all of which were abstract designs. The other two can be seen in the sculpture well, just behind Esherick’s 1934 sculpture Buck, which was also inspired by Sherwood.

The final grave marker selected by Eleanor was carved in Coopersburg black granite by Italian-born sculptor Victor Riu. Riu founded the Coopersburg Granite Company, carving gravestones with granite that he and his family quarried. Riu also worked on sculptures of his own, some of which can be seen in the collections of the Woodmere Art Museum and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Using Esherick’s design for Anderson’s grave marker, Riu worked from a large six-foot block, using an abrasive cutting wire like a bandsaw to achieve the form. Suggestive of a spiral, the form gestures gracefully upward, beyond the confines of it’s granite heft. Inscribed along the base of the stone is an Anderson quote: “Life, not death, is the great adventure.” The photo at the top of this post was likely taken at Riu’s studio in Cooperstown, PA, before being installed at Round Hill Cemetery in Marion, Virginia.

Wharton’s original attempt, Reverence, was purchased for the permanent collection of Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park Art Commission after going on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago as part of the traveling exhibition Sculpture of the Twentieth Century. After the purchase, the piece was loaned to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it remained on view for many years. It is now glimpsed by guests at our Annual Members’ Party each September when they are invited into the 1956 Workshop and home of Mansfield Bascom, Wharton’s son-in-law and Director and Curator Emeritus of the Museum.

Behind Wharton’s dining room bench rests a found piece of Coopersburg black granite, an ever-present remembrance of his dear friend.

Post written by Communications & Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.