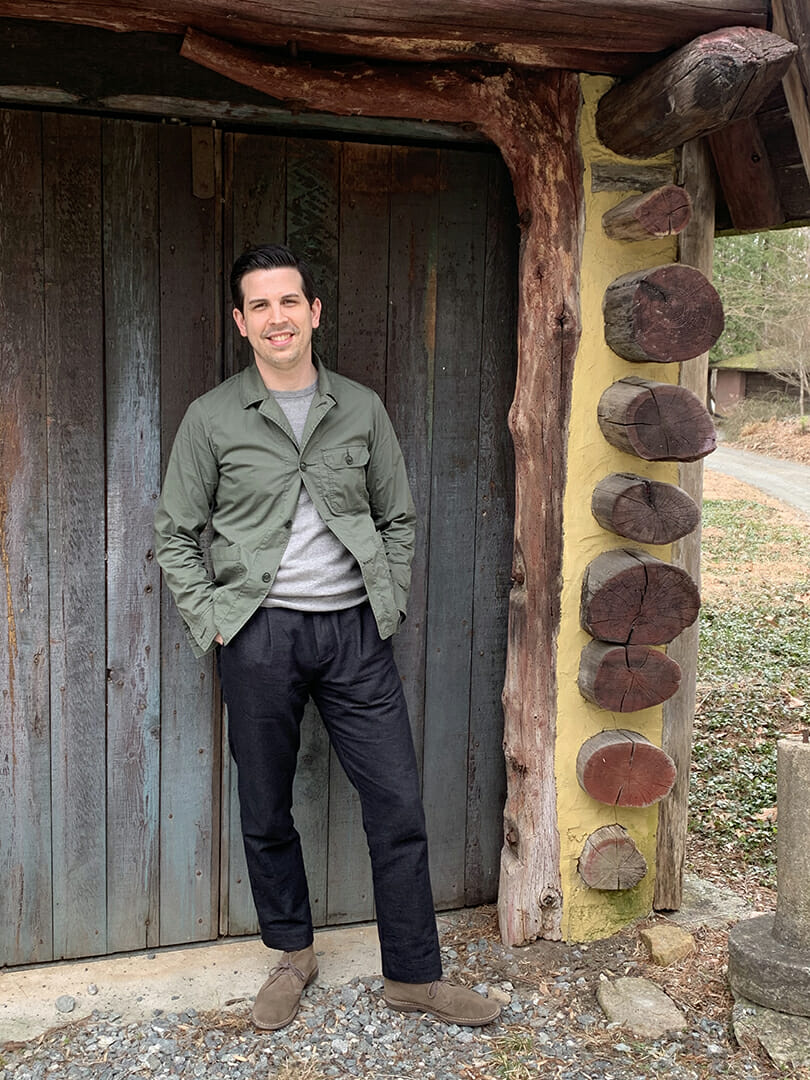

In 2020 the Wharton Esherick Museum was delighted to welcome Alex Till to the staff as our new Curatorial Assistant, a two-year position funded by a grant from The Henry Luce Foundation. Prior to joining our team, Alex worked with collections at numerous institutions, including the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and holds a master’s degree in Historic Preservation and a Graduate Certificate in Museum Studies from the University of Delaware.

We were excited to connect with Alex this month to hear about his behind-the-scenes work with the collection and why it’s so important to our plans for the future.

What has been the scope of your work at the Esherick Museum?

There are two pieces to the work I’m doing here, which go hand-in-hand with each other: collections organization and collections care. The bulk of my work is inventorying the entire collection, creating a true count of everything WEM holds with basic descriptions, details, and locations of each item. This includes everything from the furniture to dishes in the cupboard, to prints, paintings, photographs, Esherick’s clothes, and personal effects tucked away in drawers. I think I’ve gone through 800 or 900 works on paper in the last six months!

As a small site, WEM hasn’t had a dedicated staff person for their collection in the past, and so previous efforts were done sort of piecemeal, squeezed in around other museum duties. We’re finally pulling all that information together now in one digital database.

That leaves the collection care aspect – what does that work entail?

Collections care is all about keeping objects in the best condition possible for as long as possible. Alongside Emily Zilber, Director of Curatorial Affairs and Strategic Partnerships, and others on staff, I’ve reviewed handling guidelines for both staff and guests, rehoused works (which refers to the way they’re stored), and established pest management and monitoring guidelines. This care work can also include gathering recommendations from colleagues and experts like the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) which reviewed our works on paper, or Mark Anderson, the former Senior Furniture Conservator at Winterthur, to make repairs or recommendations regarding our wooden works.

We’re really at an in-between moment at WEM to follow best practices when it comes to our collections care. What we need is more dedicated storage space. For example, currently in a box of 200 prints, they are separated by tissue paper so they are not touching each other, but ideally, they should each be in their own folder, so that when you pull the folder you can handle it without any touching, and it’s also more supportive of the material. But to do that exponentially expands the amount of space that stack of prints takes up.

The proposed campus plans aim to resolve this issue, where dedicated storage and archival space would be established in a new visitor center. This would allow for proper housing of these important works on paper and documents from Esherick’s career, and access to scholars and researchers wanting to explore them. Currently, with everything stored within the Studio itself, research requests are complicated by working around the tour schedule and other activities happening in the Studio.

Esherick’s Studio offers up a unique challenge when determining where the collection objects end and the building begins.

What are the unique challenges or approaches to working with a historic home/studio like Esherick’s?

This is the first time I’ve worked with a collection dedicated to one artist that is a historic site in its own right as well. It’s been interesting to see through these objects his artistic growth over time and to see these works in the space he made for them, and for himself.

It’s also exciting to be revising and building an organizational system for the museum, rather than slotting myself into a collections department that’s fully up and running. How to organize this collection has been a unique question. Where does the object end and the house begin? I’ve created an architectural section for our inventory to capture components like the loading doors. Is the object the whole door, just the latch… are the hinges a separate object? These things aren’t in question at a traditional museum, or at a historic house that wasn’t hand-built by an artist. Or take the Spiral Staircase – it is a premiere Esherick artwork, but it’s also the only way to access the bedroom. It’s a question of balancing public access with the safest conditions for the art, where it’s not the same to share a picture of it. There’s humanistic value to using the stairs. That question of balance comes up more here than anywhere else. You feel the physicality of everything at the Esherick Museum a lot more.

Photographer Eoin O’Neill and WEM Curatorial Assistant Alex Till discover the pop of color on the back of Esherick’s 1927 Drop Leaf Desk.

In your role, you spend a lot of time dealing directly with objects in the collection. Can you talk about some of your favorite discoveries?

It’s a joy that I get to explore everything Esherick’s made, no matter what material, date, or how much importance we might put on it as a major piece. To look at one artist so comprehensively and see the throughlines in his evolution as an artist has been really exciting.

Seeing the back of the Drop Leaf Desk, that was an exciting day. We had moved it away from the wall to photograph it and discovered the back painted red. That pop of color, reminiscent of the floor color, was really interesting and really a surprise.

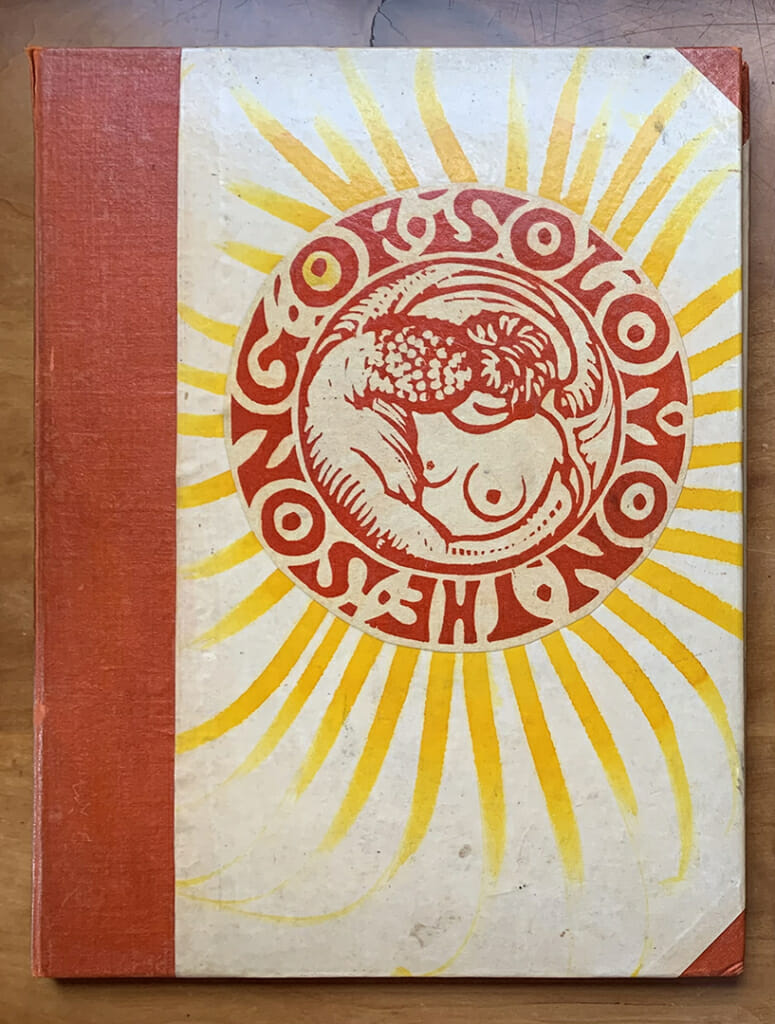

Esherick’s 1924 hand-printed and hand-lettered, The Song of Solomon, a prototype for the final publication printed by the Centaur Press in 1927.

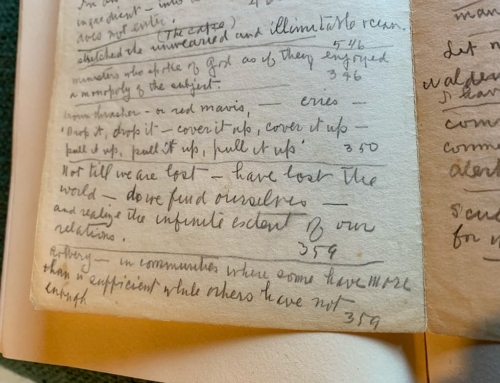

Another favorite was seeing the progression of Esherick’s work on the Song of Solomon publication. From a sketchbook with designs, to hand-printed and lettered editions that he created on his own, to early proofs and final copies printed by the Centaur Press and sold to the public. One can begin to understand Esherick’s design process through these objects. I’m all about Esherick’s prints right now – perhaps because I’ve been steeped in them for so long!

Why is this work so important for museums?

The longevity of the collection, keeping everything in as good of condition as possible for as long as possible, is an obvious need. But the other stuff – the intellectual control – is so important because it makes all the other projects at the museum so much more efficient, if not possible, from simply locating collections items to finding new ways to interpret and approach Esherick’s legacy. Creating a usable, searchable database is critical to enabling public access as well. We want to see research and scholarship around Esherick’s story expand, and these are the first steps toward providing that opportunity in a meaningful way.

This work is also the backbone of being able to loan our collection objects with confidence; you have to know what you have in order to track it and not lose pieces along that way. It opens the doors to more ambitious exhibitions with our onsite programs as well as partnerships with local and national organizations in the field. Once this inventory is done there’s always more to do, but we’re on a good path and laying a foundation that can be built on in the future.

Learn more about our archives or explore highlights from our collection.

We are always excited to see new scholarship on Esherick’s life and legacy. If you are a researcher and would like to learn more about our collection and archives please contact WEM Director of Interpretation and Research Holly Gore at [email protected].

Post written by Communications and Public Programs Director Katie Wynne.

February 2022