By now, you’ve undoubtedly heard about our exhibition with the Brandywine Museum of Art, The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick, that opened this past October. Over 80 objects including paintings, prints, sculpture, furniture, and photography have left the Studio to be exhibited in a new context in Chadds Ford. This is, by far, the largest loan we’ve made as an institution, so we dug into the thousands of objects on site and in storage that aren’t on view to display in Esherick’s Studio. Plus, we’ve received an exciting and important loan from a private collection that we’re thrilled to show to the public. In this blog post we’ll be briefly touching on some of the new arrangements and objects in the Studio, plus some of the decision making behind these changes!

We’ve long known that Esherick’s home and studio was an ever-changing space. Whether it was structural additions to his original 1926 Studio, small yet important modifications to interior architecture such as the 1930 Spiral Staircase, or a dynamic curation of objects as they were made, used, and acquired, Esherick’s home was changing in large and small ways throughout his lifetime. When Esherick’s family opened the Studio as a museum in 1972, they made the decision to keep the space largely as Esherick had arranged it. However, Esherick’s family made certain curatorial decisions to rearrange pieces in order to exhibit the artist’s legacy to its fullest possible effect. While the space has been largely static since, the exhibition at the Brandywine has given us the exciting opportunity to thoughtfully experiment with different ways of presenting Esherick’s home and studio to the public.

Bedroom Assemblage:

Archival photograph of Esherick’s bedroom, ca. 1970s-1980s

Archival photograph of Esherick’s bedroom, ca. 1970s-1980s

Archival photograph of Esherick’s bedroom, 1971.

Archival photograph of Esherick’s bedroom, 1971.

The reinstallation in the bedroom was largely inspired by archival photographs in our collection that document what the Studio looked like during different periods of Esherick’s lifetime and in the earliest days of the museum. With the large Piano Table made for Miriam Phillips leaving the bedroom, we had the opportunity and the space to reconfigure this room as Esherick likely once had it himself. The 1936 Easy Chair and 1947 Rawhide Stool that were previously in the corner of the room and a blanket chest that had been tucked at the foot of the bed have come out into the center of the room– giving the space a much homier feel. Items of rarely seen clothing such as Esherick’s cardigan and red leather hat adorn the blanket chest alongside a stack of well-loved publications. This new, yet historically informed assemblage in Esherick’s bedroom provides a snapshot in the rhythms of his daily life lived amongst his work.

Esherick’s bedroom in its most recent arrangement.

Esherick’s bedroom in its most recent arrangement.

Hannah Weil Work Table:

Replacing the large padauk and walnut Flat Top Desk is this wonderful table that, unlike most of Esherick’s work, has likely never before seen the inside of his Studio. This oak and pearwood Work Table was made in Germany in 1931 for Esherick’s friend, fellow artist, and possible love-interest Hannah Weil. Weil, who came to the United States in 1930 under the patronage of Esherick’s client Helene Fischer, was a German artist known for her brilliantly intricate ivory carvings. We can credit Fischer for introducing these like-minded artists.

Hannah Weil at her work table, 1931.

Hannah Weil at her work table, 1931.

During the summer of 1931 Helene sponsored a trip for Esherick and her artistically inclined son, York Fischer, to visit Hannah at her home in Bavaria after having returned the previous year. There, Esherick and York Fischer created this table with its warped, two board pearwood top outfit with butterfly joints, a carved hole for Hanna to fit her carving vise, and striking prismatic oak legs. The photograph above shows Helen Fischer sitting at her work table outdoors, book in hand.

Photo and photographic detail of Hanna Weil’s work table (1931)

Photo and photographic detail of Hanna Weil’s work table (1931)

While there was possibly some romance between Esherick and Weil, she would ultimately marry York and the couple lived in Germany until the end of the 1930s when they moved back to the United States and brought this table with them. The table now cohabitates the Studio’s Main Gallery with another piece Esherick gifted to Hannah: the original hanging figure rendered in cocobolo that serves as a whimsical light pull.

Cocobolo Light Pull, ca. 1930

Cocobolo Light Pull, ca. 1930

Easel and Painting:

The ample room left in the Studio’s Main Gallery gave us the opportunity to highlight a rhythm of Esherick’s early artistic practice: painting! This easel was pulled up from the Sculpture Well where it had previously displayed a large woodblock related to a Hedgerow Theatre production. This easel now displays a very unusual Esherick painting called Forest Fantasy. Unfortunately, this painting does not appear to have been documented in the ledger book maintained by Letty Esherick to track her husband’s work, sales, and exhibitions (and it’s quite possible the painting’s original title has been lost to history). However, it likely dates to the late nineteen teens to early nineteen twenties when Esherick was actively painting.

Wharton Esherick’s easel and painting Forest Fantasy, n.d.

Wharton Esherick’s easel and painting Forest Fantasy, n.d.

Rather than the typical plein air landscape paintings Esherick completed in an impressionist style, the colors that comprise this playful landscape appear to have been pulled out of Esherick’s imagination. Today, it looks much closer to the scenery in the Candy Land game than it does a Chester County winter– however, it’s likely Esherick pulled something different out of the landscape that a less artistic eye is unable to see. While the colors may be outliers when compared to the color palette we associate with Esherick today, the movement he creates in this painting accords wonderfully with Esherick’s graphic woodblock illustrations, carved antique furniture, and his full-fledged organic furniture and sculpture.

There are a few easel’s in the Wharton Esherick Museum collection, and this example appears to be the least mobile. In comparison to the other, collapsible easels left to us that Esherick could easily take outdoors to paint farmers, fields, and barns in warmer weather, it’s likely that the example now in the Studio’s Main Gallery was used indoors at Sunekrest when Esherick was using a room on the second floor as a painting studio.

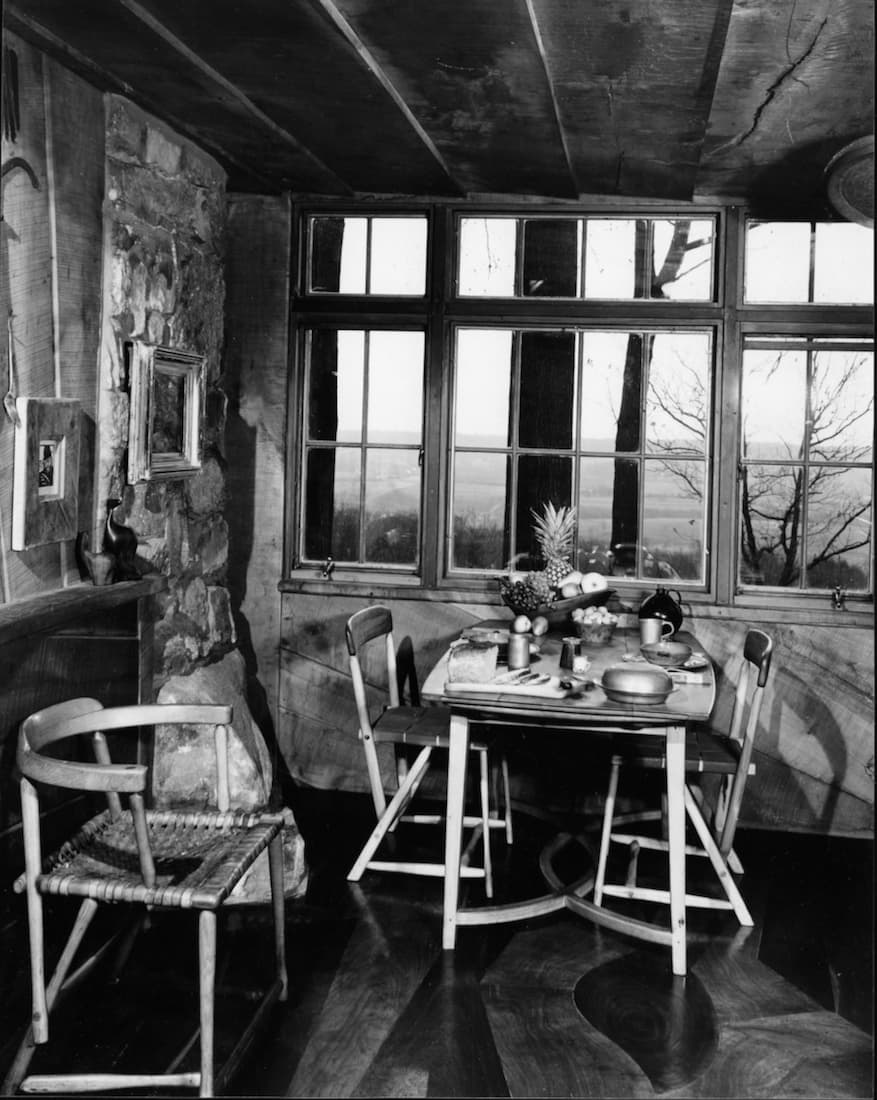

Kitchen Assemblage:

With the newfound sense of breathing space within the Studio, we took the opportunity to delve into drawers and cupboards to pull out some of Esherick’s belongings that were previously stored out of sight. In this frame of mind, we decided to set the dining room table! In choosing and arranging the tableware, we took cues from an archival photograph of the space as it was arranged for a photography shoot in the 1950s.

The photograph shows a table set with an eclectic mixture of tableware, some of which Esherick made, and some that he collected. A pineapple tops an assortment of fruit set within one of his sculpted bowls. Bread slices fall, domino style, along the length of an Esherick cutting board. A shot glass serving as a salt cellar nestles beside an object that epitomizes Esherick’s dedication to art in everyday life–a hand carved, sculptural pepper grinder.

As we began looking through the nooks and crannies of the kitchen, we found that some of the tableware from the 1950s was still there, notably Esherick’s pepper grinder, which now has pride of place at the center of the dining table. We also included plates that he made in the 1930s with Alabama ceramic artist Peter McAdams and cups that he bought from a California pottery called “Red Barn.”

Archival Photograph of Esherick’s dining room, ca. 1940s.

Archival Photograph of Esherick’s dining room, ca. 1940s.

Table setting in the dining room.

Table setting in the dining room.

In all, the movement of objects from the Wharton Esherick Studio to the traveling exhibition, The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick has given us the extraordinary chance to look back on the history of the Studio–both as an artist’s home and workspace, and as a museum–and to reflect on the choices made over the years, as well as our roles in preserving this one-of-a-kind space in ways that respect Wharton Esherick’s creative vision.

Post written by Ethan Snyder, Public Programs & Collections Manager, and Holly Gore, Director of Interpretation & Associate Curator of Special Collections

October 2024