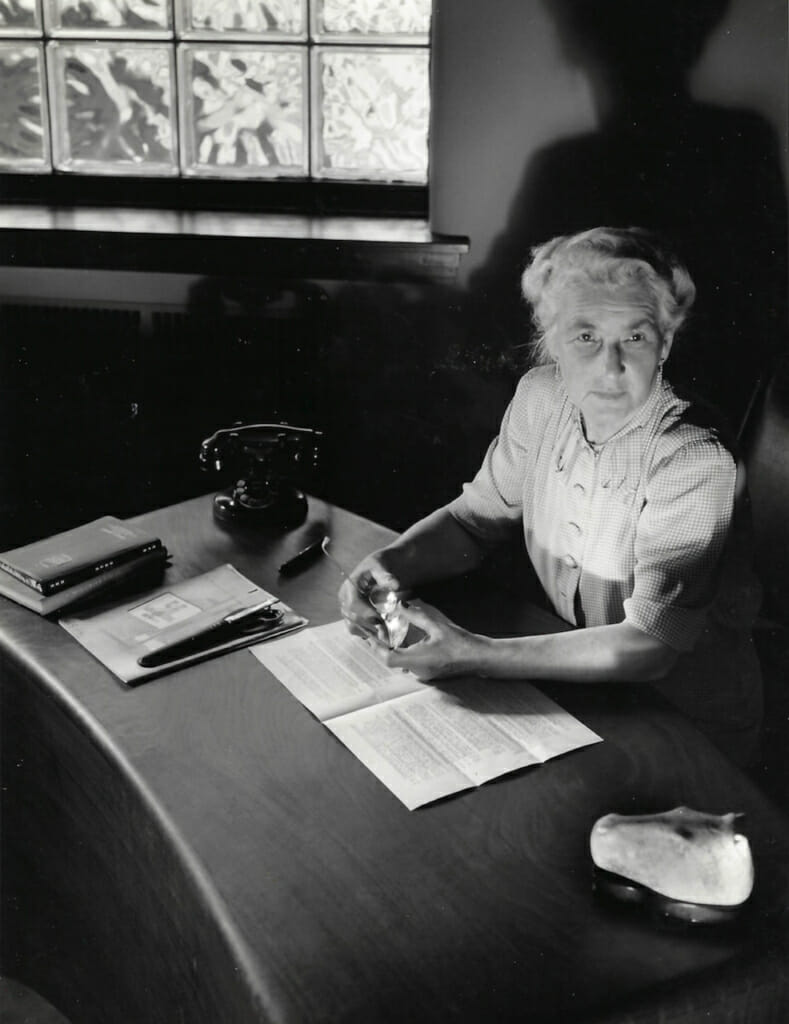

In 1942, German American businesswoman Helene Fischer became President of the Schutte & Koerting Company, a Philadelphia based manufacturer of high-pressure valves and other precision machinery. Her late husband held the position before her, and before him, her father. One of the first things Fischer did upon assuming her administrative role was to commission Wharton Esherick to create a suite of furniture for the Schutte & Koerting executive offices. A photograph taken at the factory in 1944 shows Fischer seated at her Esherick-designed President’s Desk (1943). She looks up from her neatly ordered papers, eyeglasses in hand, as if the photographer had interrupted her work. In the black-and-white image, Fischer is spotlit, with long shadows adding drama to the scene. In life, theatricality extended beyond the scope of the camera, throughout the room. When Fischer commissioned Esherick to furnish the space, she enlisted an artist’s help in setting the stage for the new era of leadership that she would usher in.

Schutte & Koerting Co. executive suite by Wharton Esherick, 1942-44. Designs include the Boardroom Table, S-K Chair, S-K Armchair, President’s Desk, Ceiling Light Cover, and Door with Sunburst Window and Carved Handle.

Esherick responded to a complex set of concerns when he completed the Schutte & Koerting commission. He met the utilitarian requirements of the job by producing the following pieces in addition to the President’s Desk: a conference table; two versions of the S-K Chair, one with arms and one without; a waste receptacle; a ceiling light; an air grille; and a door with a sculpted wood handle and sunburst patterned window. In designing these objects, Esherick would also have taken into account Fischer’s interests in décor, which leaned toward the adventurous side of modernism—often, though not always.

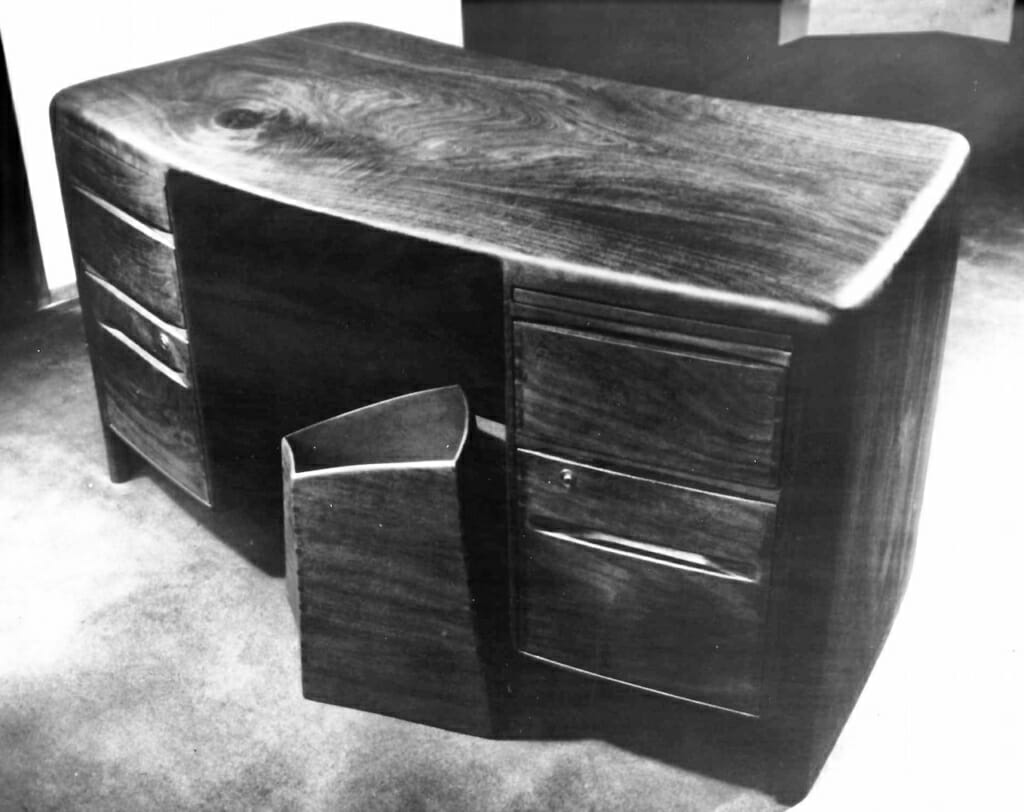

The President’s Desk is by far the more conservative of two desks that Esherick created for Fischer during their lifetimes. Its showier counterpart is a drop front Corner Desk (1931) that Fischer used at home. With the latter work, Esherick pulled out all the stops in terms of detailing, design, and woodworking virtuosity. The piece is a sculptural arrangement of prismatic forms with myriad compartments and drawers that are worked into the abstract composition. Esherick tasked his cabinetmaker, John Schmidt, with such intricacies as a secret compartment and compound angle dovetail joinery. The material he used was padauk, a costly tropical hardwood that is bright burnt orange when it is first cut. The President’s Desk, by contrast, is a plain, sturdy design softened by subtle curves and asymmetry. Its material is dark brown walnut. Seen from the front and sides, it has the solidity of a bread loaf.

The dissimilarities between the two desks doubtless had to do with the ten-year gap between their making as well as Esherick’s penchant for experimenting with new ideas. But certain disparities would likely have arisen from a unique function of the President’s Desk and the whole of the Schutte & Koerting executive office furniture suite: to communicate Fischer’s vision for a progressive company moving forward with her at the helm.

Fischer became the President of Schutte & Koerting at a time when women were entering factories in unprecedented numbers. This newly tapped workforce flowed into a labor void left by men who had gone to fight in World War II. Most of the jobs that women workers filled were manual. Fischer was the rare woman in manufacturing to have an executive role. During an era that celebrated Rosie the Riveter as an emblem of home front resilience, Fischer had to fashion her own image of feminine strength. In her position at the top of the corporate ladder, she doubtless faced adversity in the form of people questioning her authority because she was a woman. It is therefore unsurprising that she would choose for her office a desk that was weighty, dark, and plain; a no-nonsense design to counter negative stereotypes equating women with weakness and frivolity.

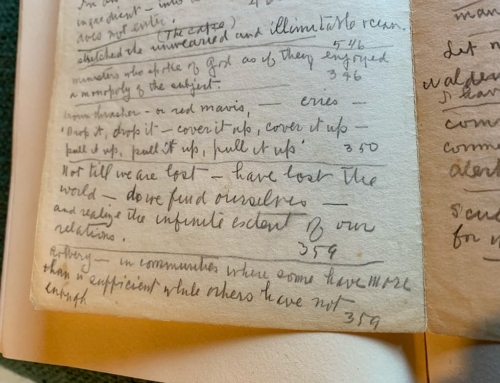

When Fischer glanced up from her President’s Desk during the photo shoot of 1944, she did so from within a room that was outfitted in the spirit of dynamism, adventure, joy, and above all, modernism. Esherick had brought to the project his signature use of organic sculptural form in furniture. A composition of arcing braces that supported the conference table had a surprising echo in the curved legs of the S-K Chairs. The cover for the overhead light showed a lacy, swirling pattern that suggested water flowing in nature, as in churning waves or wind-blown clouds smeared across the sky. Everywhere, skewed geometries implied movement. Was the triangular motif on the door window a rising sun? Or the horizon as seen from a tilted boat? Amidst a vision of the Schutte & Koerting Company sailing into modernity, the President’s Desk was an anchor, an immovable authority.

Select works by Wharton Esherick from the Schutte & Koerting Company executive suite are on view in the exhibition, Daring Design: The Impact of Three Women on Wharton Esherick’s Craft at the Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, PA from September 10, 2021 – February 6, 2022.

All photographs in this post are from the Wharton Esherick Family Papers at the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Post written by Holly Gore, Director of Interpretation and Research

January 2022