This month we were excited for the opening of Wharton Esherick: An Artistic Legacy Through Necessity, an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) which explores the productive relationship between applied and fine arts within Esherick’s work and places his practice in conversation with recent PAFA alumni. Among the works on loan from the Wharton Esherick Museum is Esherick’s 1958 Cabinet Desk. This marks the first time this desk has left the Studio since we opened as a museum in 1972 and, as a result, this became not only an opportunity to share the desk with new audiences at PAFA but also to take a deep dive into what exactly was stashed away in each drawer!

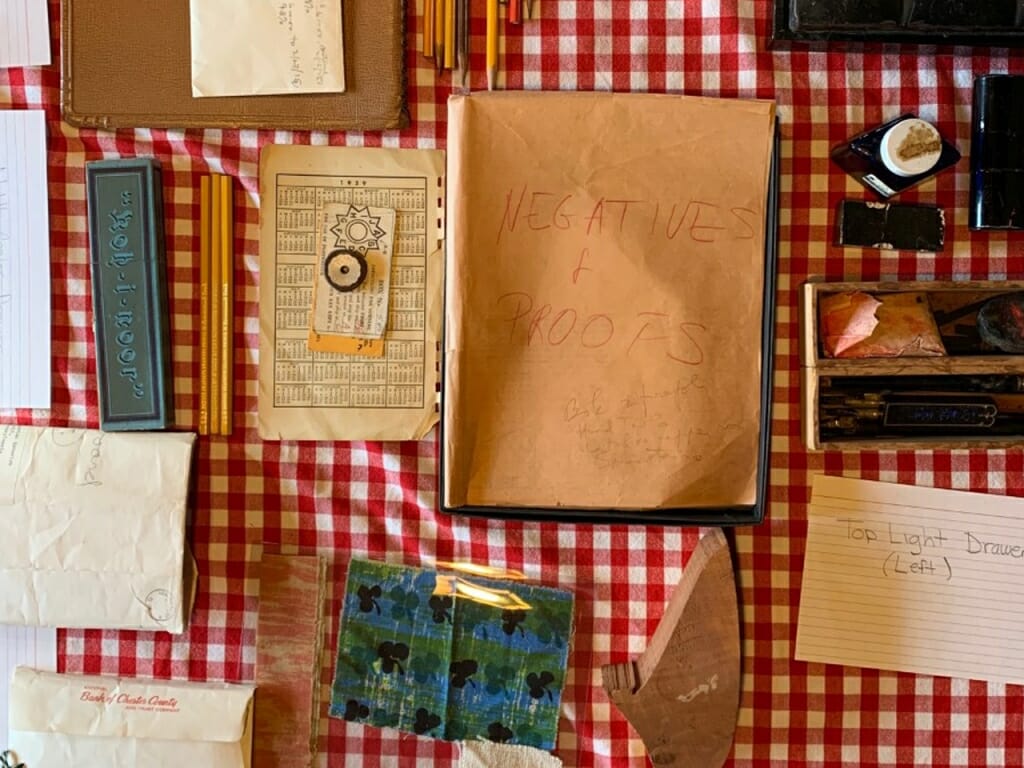

While the Cabinet Desk is indeed a work of art, it is also what its name suggests: a cabinet. And by preserving Wharton’s Studio as it was when he lived and worked here, we continue to use it as such, with everything from photographs and correspondence to art supplies stored within. Before the desk was moved from its home in the Museum, the contents had to be completely inventoried and cataloged. Each drawer of the desk was taken out, photographed, and delicately relieved of duty as each object was removed, recorded in detail, and carefully relocated to temporary storage. With hundreds of objects to wade through, the process can seem overwhelming, but the end result is incredibly rewarding. Highlighted here are just a few of Wharton’s belongings that illuminate his artistic life and the rich material culture he left behind.

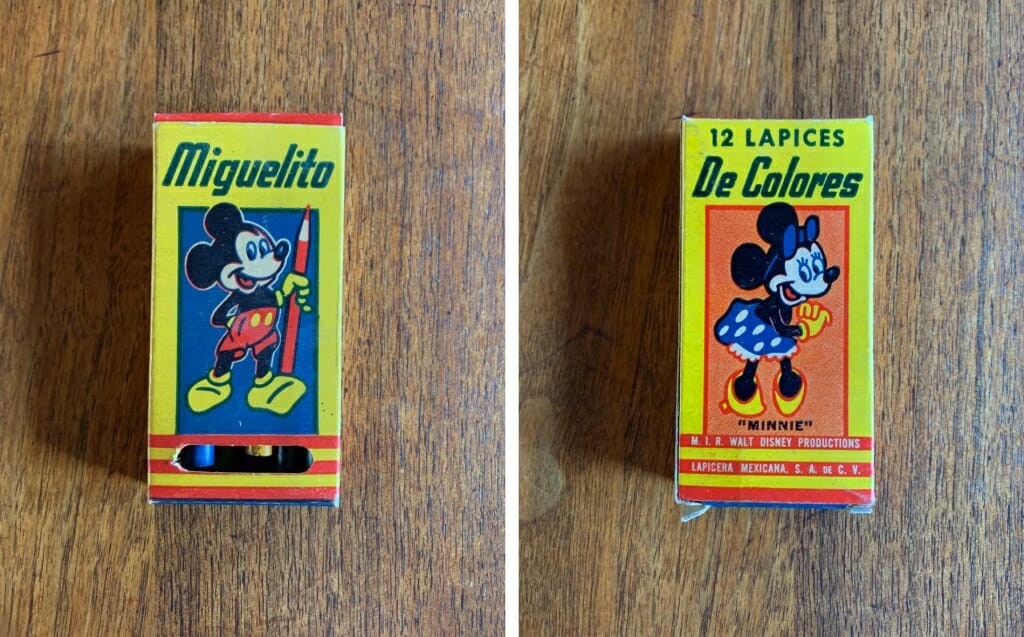

Lapices de Colores

Wharton’s drawers are filled with small, colorful containers sporting gorgeous graphics of the highest quality. Among them, one stood out to me: a rectangular cardboard box labeled “12 Lapices De Colores” with printed images of “Miguelito” and “Minnie” (who we may know better as Disney’s Mickey and Minnie Mouse) on the front and back. The name of the company that produced this collection of colored pencils, Lapicera Mexicana, S.A. de C.V, is also marked on nearly every surface of the box.

Lapicera Mexicana was founded in 1944 in Mexico City. It has since shut down, but was at one time Mexico’s premier producer of lead pencils and art supplies. The timing of Lapicera Mexicana’s active presence lines up with Wharton and Miriam’s road trip to Mexico in 1947 — it is entirely possible that one of them brought these pencils home as a souvenir, or purchased them to use on the trip. The pencils themselves were most certainly used, as one is missing (replaced in the box now with a stick of chalk) and all were sharpened by a knife.

Koh-I-Noor Pencils

If you are an artist, the name “Kor-I-Noor” may be familiar to you. I am by no means an artist, so what drew me to these pencils was not the brand, but the sheer quantity that Wharton had in his possession. In the Cabinet Desk were twelve boxes of Koh-I-Noor pencils of various hardnesses and states of use, in addition to many loose pencils in smaller inset boxes or troughs. Based on the vast number of boxes, it seems quite possible that Koh-I-Noor Hardtmuth was one of Esherick’s favored brands!

Interestingly, Koh-I-Noor Hardtmuth invented the hardness scale still used for art pencils today. Founder Josef Hardtmuth created a process in which pure graphite could be powdered and mixed with clay, making it easier to encase in wood and allowing for different “purities” of graphite. His grandson, Franz, ultimately categorized these states of “purity” and created a scale ranging from H (hardness) to B (blackness). Have you ever noticed the “HB” on standard No. 2 pencil? That “HB” means it’s smack dab in the middle of the scale.

In addition, the habit of making pencils bright yellow began with this company. Koh-I-Noor Hardtmuth was originally named L&C Hardtmuth British Graphite Drawing Pencils but rebranded for the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris. The name “Koh-I-Noor” is drawn directly from the British Crown Jewel of the same name; a yellow diamond that, at the time, was the largest diamond in the world. The yellow coloring of the pencils, in addition to the blatant connection in name, was likely meant to associate the brand with quality and luxury, while remaining affordable to the general public. Certainly, Wharton’s brand loyalty is a testament to Koh-I-Noor Hardtmuth’s enduring influence and importance to artists and creators.

Wood Samples

In one of the less densely occupied drawers, I found six small pieces of wood. More than just scraps, they appear to be wood samples, showing not only a variety of wood types but various finishes and shapes, too. Of these six pieces, two are labeled with the name of their respective wood; one reads “Cherry” and the other “Cottonwood C.” While their shapes vary, all but one are flat and geometric, with beveled edges and angled facets very typical of Wharton’s work. The outlier of these is much thicker and cut with a large sweeping curve on one edge, and is also unfinished — the rest seem to be finished in linseed oil (typical of Wharton) or with polyurethane.

The last detail, and most fascinating to me, is that two of the pieces have small carvings in them. One has three nearly identical lines gouged on the edge, almost as if Wharton was playing with his signature. The second has only one line carved and a large “E” in pencil right beside it. Both of these suggestions of signatures, in addition to the other characteristics, imply that these “scraps” were wood samples that Wharton used to show his clients their options when commissioning work from him. They are small enough to send in the mail or bring along to a patron’s home or office.

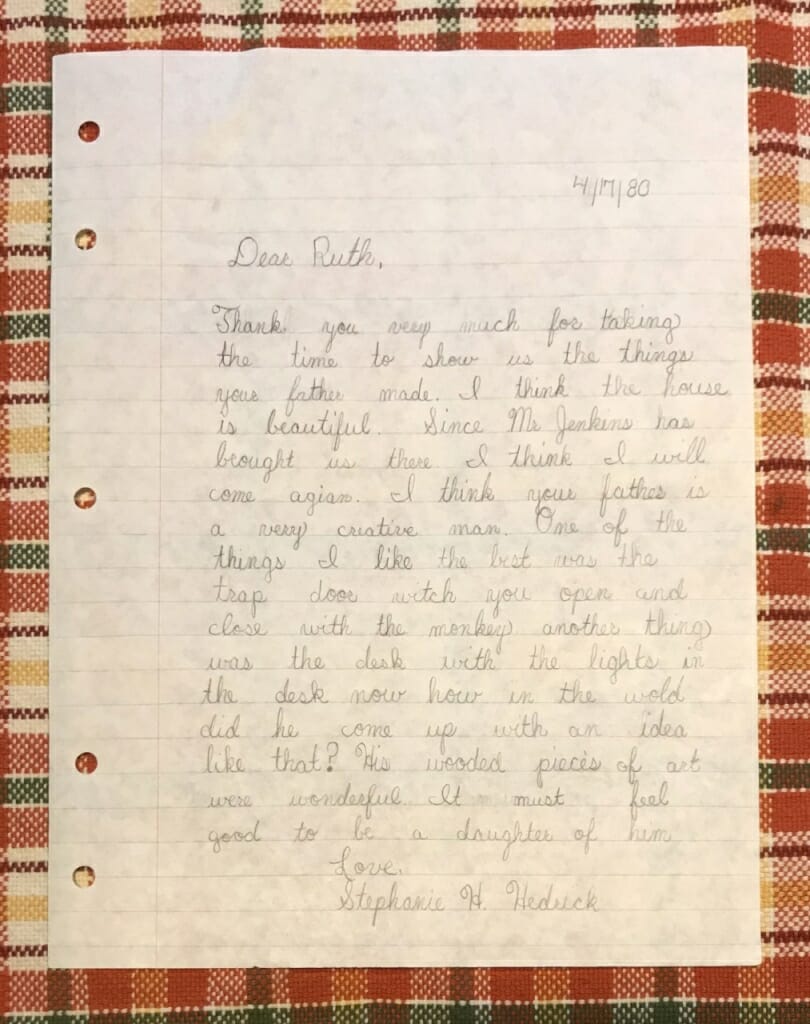

Letters to Ruth from Sugartown Elementary Students

The objects in the Wharton Esherick Museum collection, like the ones I discussed above, are fascinating on their own. However, they don’t mean nearly as much if they don’t reach our visitors. The most touching object (and by far my favorite) was an envelope addressed to Ruth, Wharton’s daughter and first President of the Museum, from a class at Sugartown Elementary School that had come to the Museum for a field trip. The seventeen handwritten letters, all dated April 17, 1980, are either addressed directly to Ruth or are formatted as journal entries, thanking her for giving their tour and sharing the space with them. If you’ve ever visited Esherick’s Studio before, I’m sure these highlights from the students’ letters will resonate with you!

“Today was the best day I’ve ever had.” – Jenny Hewitt

“It was very very very very good.” – Gary Stevens

“Even though I never met Mr. Esherick I know that he is a wonderful man.” – Andrea Carmone

“Dear Ruth, Thank you very much for taking the time to show us the things your father made…I think your father was a very creative man…It must feel good to be a daughter of him. Love, Stephanie H. Hedrick”

This month’s blog post was written by Visitor Experience Coordinator Julianna LoMonaco. Julianna first became involved with the Wharton Esherick Museum as a volunteer and intern, working to accession and process our photograph archive. During our tour season, she is now an essential part of our visitor experience staff, welcoming and orienting guests to the Studio and giving tours as needed. Julianna recently received her BA in Art History of Arcadia University where she wrote her thesis on Wharton’s collaboration with architect Louis Kahn on the 1956 Workshop.

January 2020