With a snowy wonderland outside the Studio doors, we’re reminded of Esherick’s winter woodcut scenes and the artistic freedom he found through printmaking. The graphic nature of woodcut printmaking seems perfectly suited for rendering a snow-covered world – and we’re excited to highlight a few of Esherick’s winter landscapes in this month’s blog post! We also invite you to join our ‘Winter Woodcut Spotlight Talk’ on December 29th to explore more of Esherick’s snowy scenes.

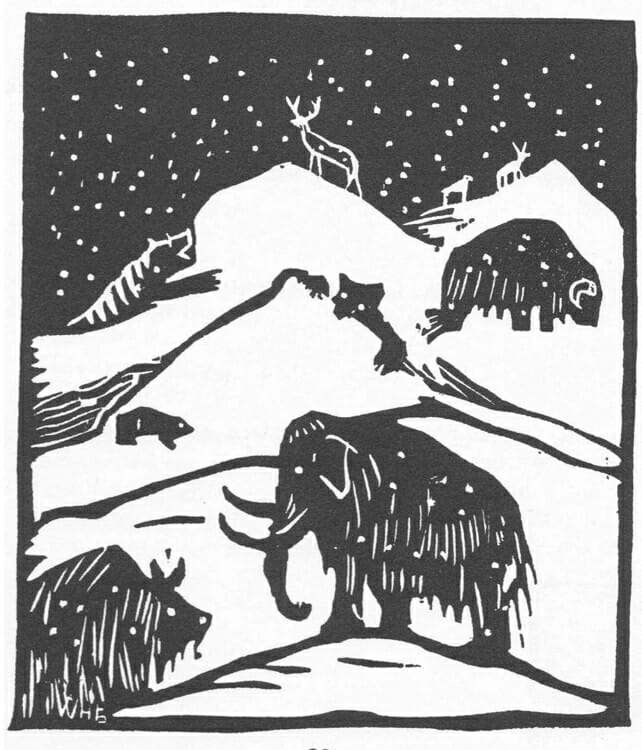

Change, Change, Change, 1922, woodcut, Wharton Esherick.

Esherick’s first attempts at woodcuts came about through his chance meeting with the author Mary Marcy in the artist colony of Fairhope, Alabama in 1919-1920. Marcy was at work writing a children’s book of poetry on evolution and Esherick had recently acquired a set of carving chisels to create hand-carved frames for his paintings. The two struck up a friendship and Esherick, inspired by one of her poems, carved a woodcut illustration. Marcy, inspired by Esherick’s image, wrote another verse, and so it went, back and forth – a collaboration was in motion. (If you love this idea – check out our Reverse Storytelling At Home Activity inspired by their collaborative process!)

The resulting publication Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk includes 74 woodcuts by Esherick, including the wonderful snowy scene Change, Change, Change. The accompanying poem of the same name includes playful tales of “The Age Ce-no-zo-ic” which “Required the stoic, In order to grow and survive, a living contraption, with gifts of adaption, And the mammals began to arrive.” Esherick’s illustration, and others from this series, are charmingly rudimentary but not unskilled. The print is lighthearted and efficient, capturing concisely the wooly mammoths and prehistoric animals well-equipped for their snowy surroundings.

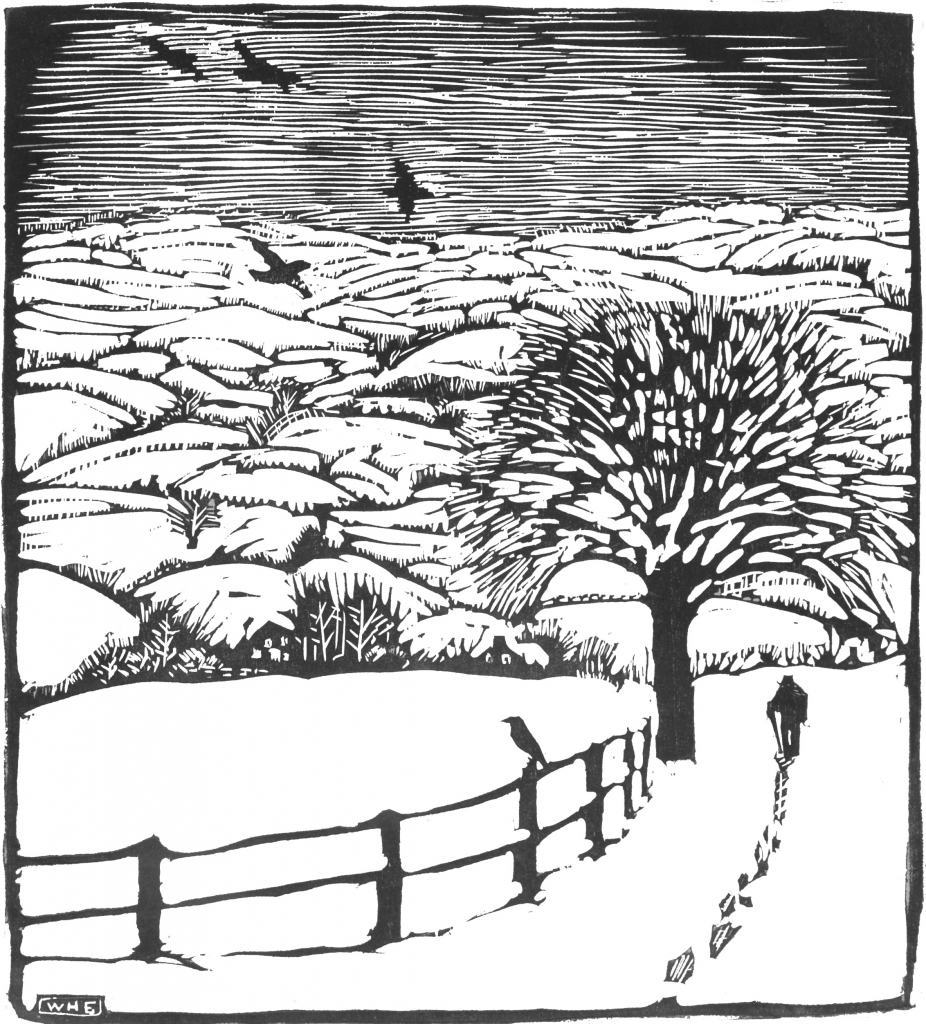

January, 1923, woodcut, Wharton Esherick.

From here, Esherick’s printmaking takes off. Although Esherick often felt ‘over-trained’ as a painter and struggled to find a unique voice in that medium, printmaking equaled freedom. He produced more than 380 blocks throughout the 1920s and 1930s alongside his explorations into furniture making. The attention of friends and curators like Carl Zigrosser, Curator of Prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, encouraged his new pursuit, as well as a growing relationship with Centaur Press to illustrate limited edition publications. A number of Esherick’s prints were also published in The Century, The Dial, The Forum, and Vanity Fair magazines.

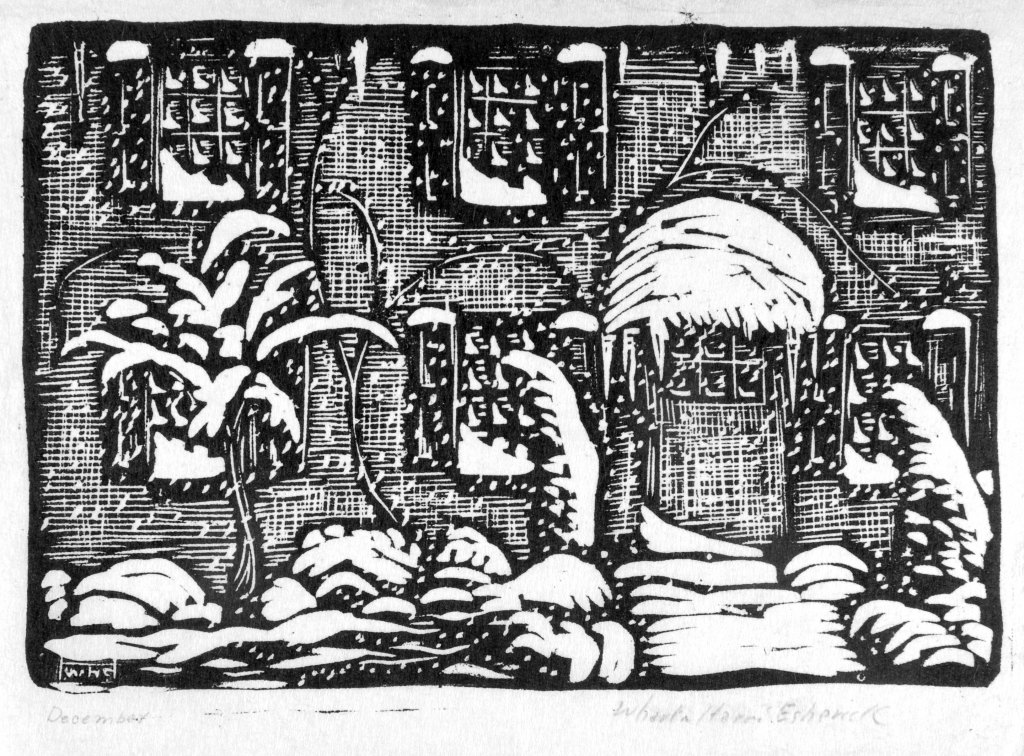

December, 1923, woodcut, by Wharton Esherick.

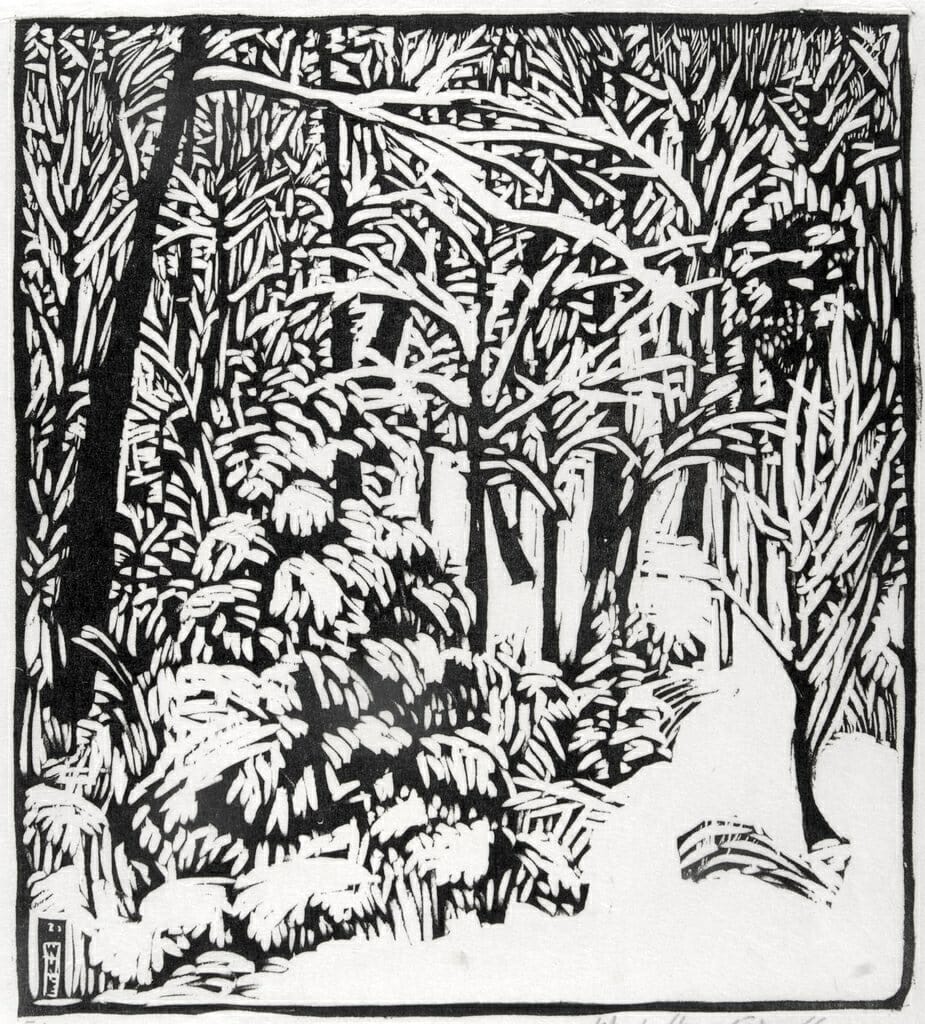

February, 1923, woodcut, Wharton Esherick.

January, February, and December are three winter scenes that capture Esherick’s developing skill and style in this new medium. These prints, all dated 1923, were published in The Century, a monthly magazine which included a mixture of journalism, literature, and poetry. Esherick takes a distinct approach to rendering the winter landscape in each composition, varying line weight and direction to different emotive effect. January captures the solitude and quiet of a winter walk, while in December, the home fills the page. In February, our view is a busy and dense forest of snow-covered branches with scarcely a distinction from tree to tree.

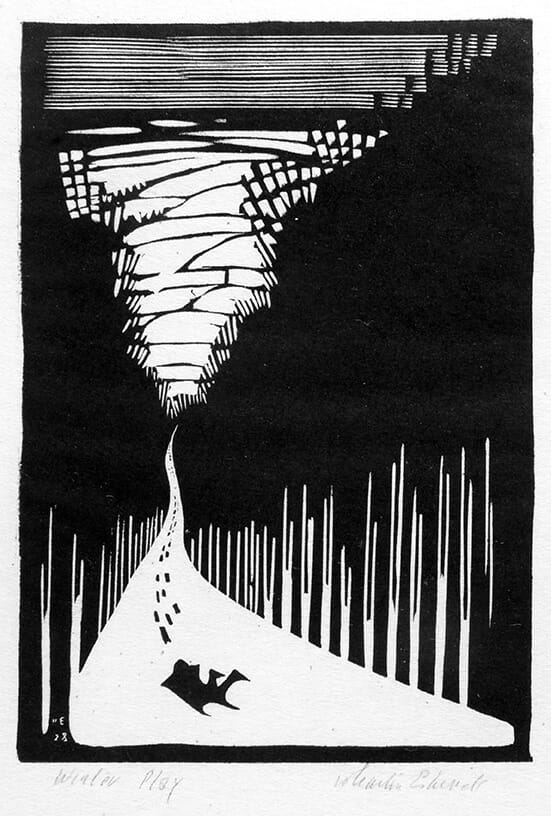

Winter Play, 1928, wood engraving, Wharton Esherick.

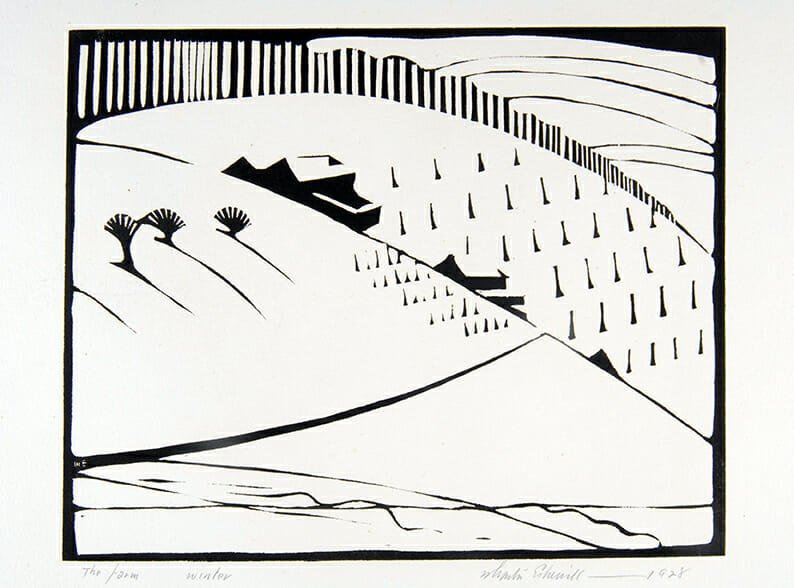

The Farm – Winter, 1928, Wood engraving, Wharton Esherick.

As Esherick continued to work in woodcuts his style evolved. In two winter scenes from 1928, Winter Play and The Farm – Winter, we can see Esherick’s prints transitioning from the romantic representation of his earlier works to a more Modernist style. Areas of both compositions are simplified and smoothed down to their essential forms.

Nature, agrarian life, and his own circle of friends and family were regular subjects for Esherick’s prints, and we see these themes carry throughout his artistic life. The Paoli countryside features prominently, as does his own home and those of close friends and patrons. December is, in fact, a depiction of Sunekrest, the Esherick family farmhouse, just down the hillside from the Studio. In Winter Play, Esherick has captured his daughter Ruth sledding down the long slope of Diamond Rock Hill where Sunekrest is located. Esherick, whether he was making the furnishings of his Studio or carving a woodcut block, need not search much farther than his own home for inspiration.

Read our ‘Closer Look at the Holiday Notecards’ blog – or check out our Winter Woodcut notecard packs in our online shop.

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

December 2020