Can you imagine a sixty-foot-high Wharton Esherick sculpture? In 1952, Esherick envisioned such a feat: his submission to the International Sculpture Competition to design a monument to the “Unknown Political Prisoner.”

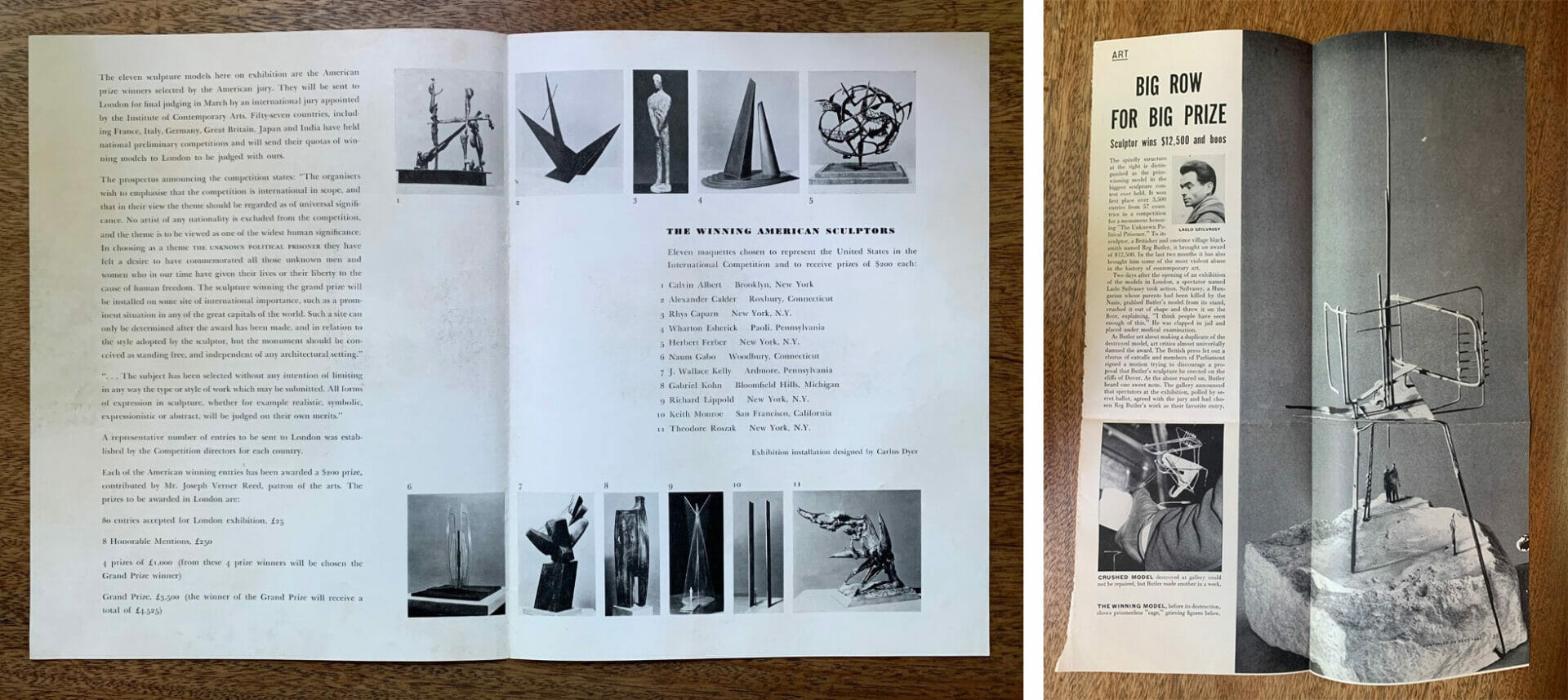

The competition, sponsored by the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, solicited proposals from around the world, with juries established in each participating country and a final selection held in London. In the United States, 199 submissions were narrowed down to eleven finalists by a jury of professionals including Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Director Andrew C. Ritchie. Esherick’s model had made the cut and was exhibited at MoMA (January 28 – February 8, 1953) along with the other finalists, before heading off for exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London. In good company, Esherick’s fellow American finalists included works by well-known sculptors such as Calvin Albert, Alexander Calder, Rhys Caparn, Herbert Ferber, Naum Gabo, J. Wallace Kelly, Gabriel Kohn, Richard Lippold, Keith Monroe, and Theodore Roszak.

The theme, as described in MoMA’s invitation to the event, was “in commemoration of all the unknown men and women who have given their lives or liberty to the cause of human freedom in our time.” For his submission, Esherick proposed Aspiring Pair: a fifty and sixty-foot high pair of sculptures, gracefully curving and ascending. Esherick seemed to draw on two previous works in particular for his design: his 1951 ebony sculpture The Pair, in which two slender forms join and spiral together seamlessly, and the grave marker he designed for his friend, the renowned American author Sherwood Anderson.

The Pair (1951, ebony), and Sherwood Anderson’s grave marker both inspired elements of Esherick’s proposed monument.

The model Esherick submitted is white pine painted black. For the final piece, he proposed either Coopersburg black granite or “metal – preferably polished stainless steel.” Esherick had selected Coopersburg black granite for Anderson’s grave marker as well, which further suggests that he envisioned the form for this monument as an extension of Anderson’s grave marker that reaches higher into the sky. Esherick also made notes on scraps of paper that framed the Aspiring Pair as “parents ” and “man and woman,” two themes that echo his concept for The Pair, which was inspired by his relationship with his partner Miriam Phillips. Of the eleven American finalists, most were abstract and ranged from complex linear webs to solid, simplified structures. Esherick’s work certainly skewed toward the latter, paring his forms down to their essence, as he did in his sculpture, furniture, or even in a building itself.

The catalog for the International Sculpture Competition: The Unknown Political Prisoner at the Museum of Modern Art shows Esherick with his fellow American finalists. The clipping on the right highlights the grand prize winner Reb Butler.

Aspiring Pair was ultimately sent off to London with the other finalists, joining the work of artists from 53 other countries. The scale of the competition was impressive; a total of 80 artworks had been selected from 3,500 international submissions. In a letter to Esherick in April of 1953, the ICA’s International Sculpture Competition Chairman Anthony J. T. Kolman stated that over 25,000 visitors had seen the exhibit at the Tate Gallery to date. Not everyone found the abstract work acceptable, however. Grand prize winner Reb Butler’s piece, a wiry form reminiscent of a radio tower, was crushed by a visitor upset by the representation of humanity in such an abstract way.

Reb Butler’s piece, which was proposed to stand between East and West Berlin, was never realized as a final placement site could not be agreed upon. Of course, without the grand prize Esherick’s vision would never be realized either — but the model, which sits unassumingly on display by the Studio’s south window, helps us imagine what an awe-inspiring monument it might have been.

Reb Butler’s piece, which was proposed to stand between East and West Berlin, was never realized as a final placement site could not be agreed upon. Of course, without the grand prize Esherick’s vision would never be realized either — but the model, which sits unassumingly on display by the Studio’s south window, helps us imagine what an awe-inspiring monument it might have been.

Post written by Communications & Public Programs Director, Katie Wynne.

June 2021