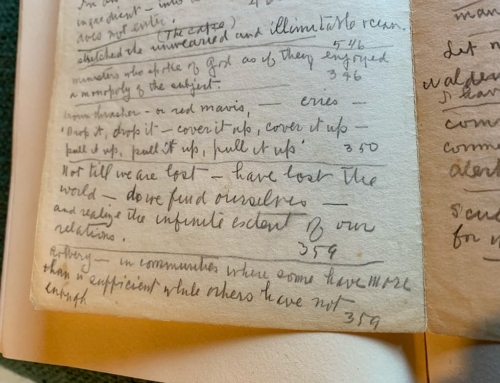

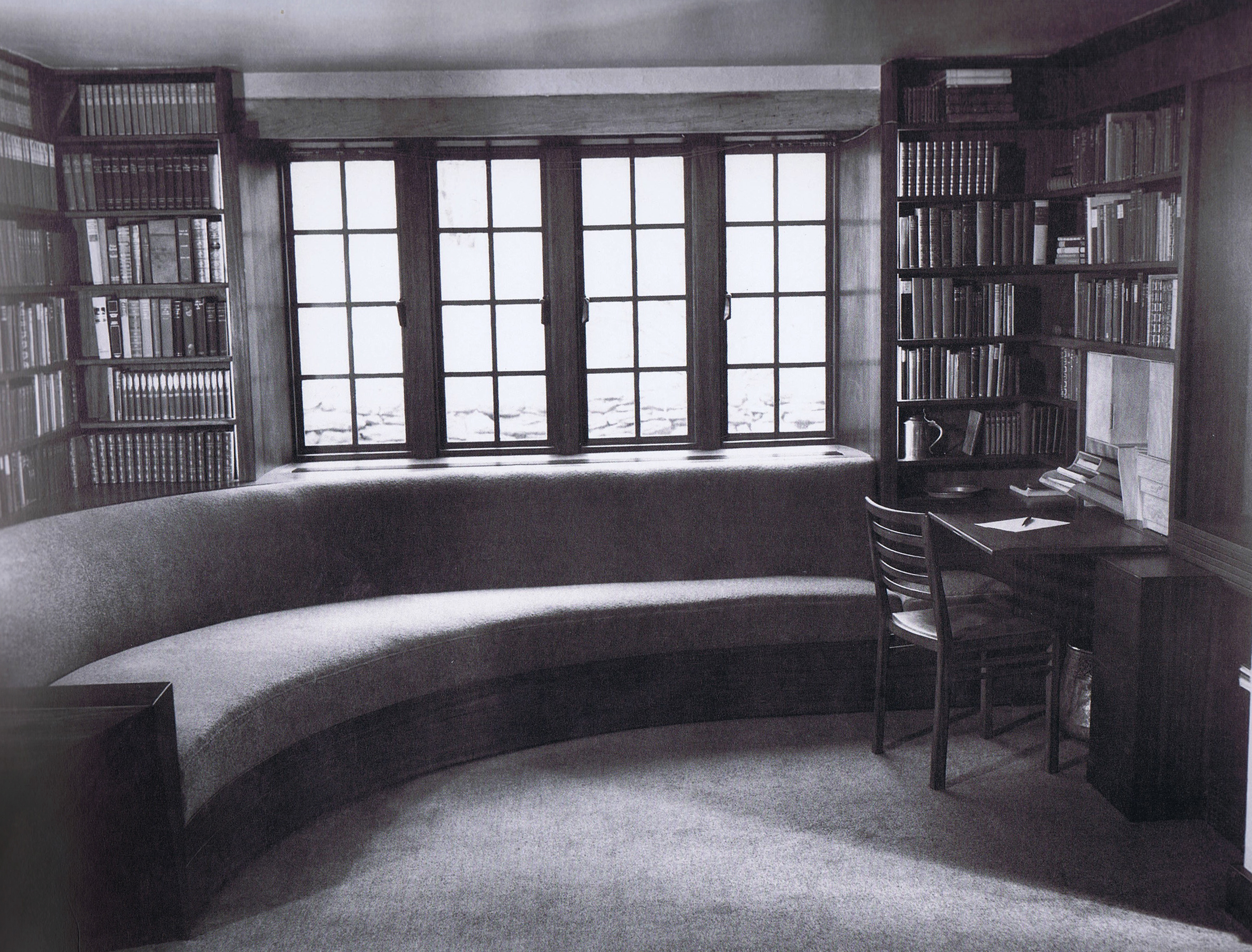

Commissioned for the Curtis Bok House (shown here) this sofa was returned and can now be seen in Wharton’s bedroom.

Someone once asked during a tour if Wharton ever made a mistake. It just so happened the tour guide being asked this question was Miriam Phillips, Wharton’s companion for the latter half of his life. She thought momentarily and replied that she couldn’t say for sure, but sometimes she was upstairs and heard a piece of wood go clanging across the studio followed by a loud curse, and she suspected that might have been Wharton making a mistake!

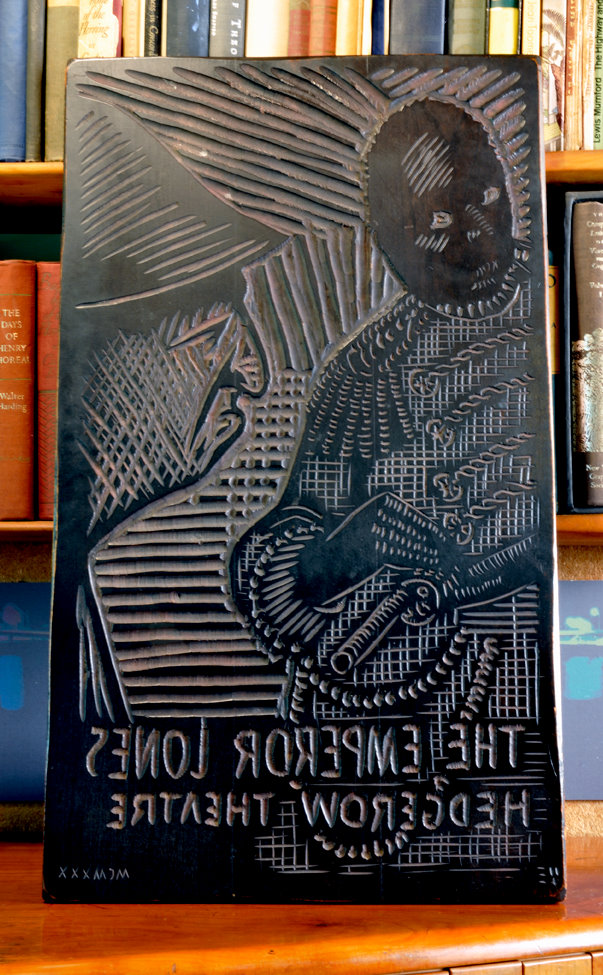

Perhaps a mistake he could live with – the “J” in this Emperor Jones poster has not been reversed on the woodblock. Photo by James Mario.

Revered by Sam Maloof and Wendell Castle, honored by the American Institute of Architects with its Gold Medal for Craftsmanship and considered by so many to be a genius of American furniture design – it’s easy to forget that Wharton Esherick had his fair share of missteps along the way. Wharton’s home, in this way, provides a valuable and unique look at the creative process – a space rightfully peppered with not only his personal, most beloved sculptures, but also the imperfections and experiments that are part of any rigorous artist’s journey. Wharton would joke that fireplaces were made for mistakes, but in truth he lived among so many of his own pieces (from returned commissions to early prototypes yet to be resolved) that were grounded in growth and exploration over perfection.

Wharton kept shortening the “nose” of this wall-mounted dinner gong, but could never find a good note!

One such piece, the gracefully curved sofa made for the library alcove at the Curtis Bok House in 1935 was returned after about a year in it’s intended home. The Boks requested that Wharton replace it with a straight one citing that Mr. Bok’s friends would only sit on the narrow ends, rather than have their feet dangle off the edge. Mrs. Bok had a complaint also – when she napped on the sofa she kept rolling off! Wharton continued to work with curved and sometimes very deep sofas, however, which would come to be an iconic design for him in the 1950’s and 60’s.

The sofa wasn’t the only commission Wharton found himself living with. Pieces could be refused for a number of reasons, some deemed too expensive, as with his 1950 Dresser (somewhat surprising considering he often undercharged for his own labor), others for being too unconventional, as with his small Macassar ebony crucifix. Wharton’s artistic experiments, whether structural or conceptual, were not all successful, but they were an essential part of exploring how far his creations could be pushed, pulled and reinvented.

Two chairs Wharton kept in his dining room are great examples of Wharton reminding himself of what NOT to do. He had three criteria for chairs – they should ‘look good, feel comfortable, and be strong enough for a man to lean back in- because he will’. The Spindle Chair met only two of Wharton’s three criteria for a good chair, as it’s straight, narrow pieces along the back were not especially comfortable. He learned from this and improved the design with future chairs like the World’s Fair Chair now seen in Wharton’s bedroom, where he used wider curved pieces for the back. The other chair, Dining Chair, Wharton designed for use around a dinner table. The woven fabric is angled at the seat, pushing the diner towards the table, which Wharton found was uncomfortable for any other use. Of course, if you were concerned about dinner guests overstaying their welcome this might not be a mistake at all!

Wharton had a certain irreverence with his own work – a practicality. His furnishings were not to be treated too preciously but rather to be lived with comfortably, acquiring age and evidence of use along the way. If a piece of furniture needed to be cut in half for an elevator ride and reassembled to make it into a new home (which was the case a least once!), well, Wharton would do it. A piece could always be changed, even years after it was made. The Flat-Top Desk, which was first designed with an aluminum top, is a perfect example. Wharton eventually replaced the aluminum with a walnut top, stating later, “It was too cold. Wood is intimate, it’s alive, metal is uncomfortable, plastic just won’t do,” though he had been willing to try it out as a new material. The replacement top would be a slightly boat-shaped piece of walnut which Wharton swapped out yet again with a second walnut top (using the first walnut piece for a coffee table). In this way, he allowed his forms the fluidity to adapt and change with any number of circumstances or his own artistic compass.

There are countless other examples throughout the house of Wharton’s perseverance (and pitfalls), though we don’t intend to list them all. Rather to this end, we remind ourselves (artists or otherwise) not only of the dedication required of the creative process but the willingness to exist in a space of uncertainty and invention, even if it means an occasional mistake!

The Flat-Top Desk, made in 1929 and shown here in the farmhouse, with it’s original 1/4 inch aluminum top.

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.