In 1935, Wharton Esherick began work on his largest commission, the Curtis Bok house. Approached initially by Curtis Bok to build bookshelves, Esherick – with the help of several collaborators and contractors alongside him — transformed the interiors of this impressive stone house in Philadelphia’s Main Line suburbs into works of art, designing and creating comprehensive, wholly considered spaces (think sofa, wall panels, bookshelves, desks, phonograph cabinets, fireplaces, staircases, and more). The ambitious project dominated Esherick’s studio time for multiple years, and with so much work to complete there were bound to be a few adjustments – and a few differences in taste along the way!

Bok House – Music Room, Photograph by Edward Quigley, 1938. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection.

Bok House – Corner of Music Room Showing Stone Fireplace, Photograph by Consuelo Kanaga, circa 1937. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection.

The music room of the Curtis Bok house provides one such example of a playful dispute between client and artist. The oak paneled room, intended as a space for entertaining guests and listening to music, featured an oil painting on hinges with an intricately carved wood grill underneath. The energetic and radiating lines of the grill hid the speakers for the music system. A mark of Esherick ingenuity at first glance, but then the question arises – why would Esherick cover this form? According to Esherick’s nephew Joseph, a playful dispute between Curtis Bok and Esherick lies behind this final design.

Joseph Esherick, who would go on to become a celebrated architect in his own right, worked with Wharton on the Bok house project. In his oral history collected by the museum, Joseph recounts how Bok and Esherick “battled” over this aspect of the music room’s design.

“One thing I remember was when [Wharton] got the damn room finished – Curtis Bok, you know he was a great sailor, and he had this marine painting. I don’t know whether it was of a sailboat or something or just the sea, but sort of a realistic painting of big waves and moonlight on the ocean, but it was a great big thing about four feet wide by three feet high, and Wharton had made this beautiful grill over the fireplace and that’s where the music came out. It was a marvelously made grill. And Curtis Bok didn’t like the grill, so he came in and hung this canvas over it, on the damned thing, so [Wharton] hinged the top of the painting and then he made this very elegant stick and he put a hook up in the ceiling – all just beautifully done, the stick the way nobody else could make a stick. And when Wharton would come in he’d take the stick and raise the painting up against the ceiling, and when Curtis Bok would come in the room he’d go over and get the stick and put the painting down, so you could always tell who was in the room and who wasn’t.”

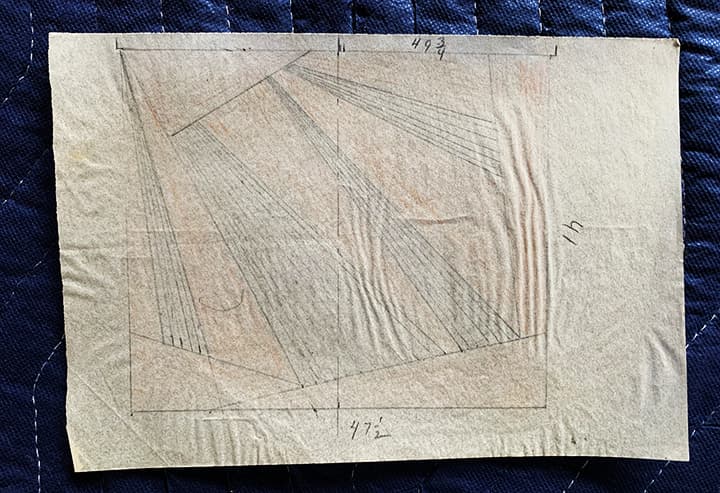

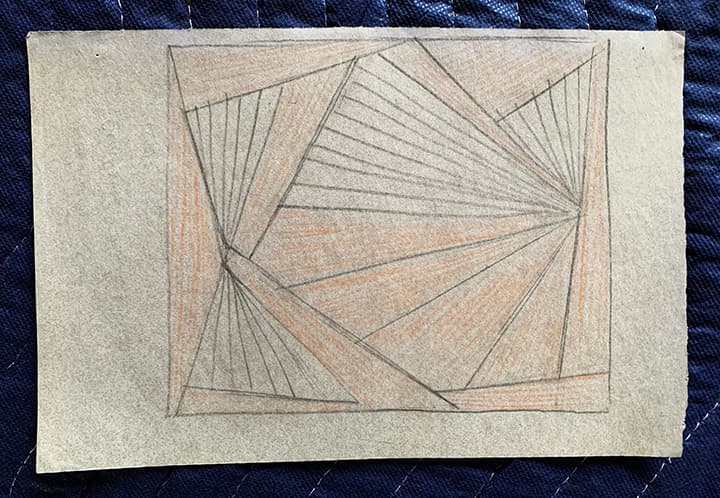

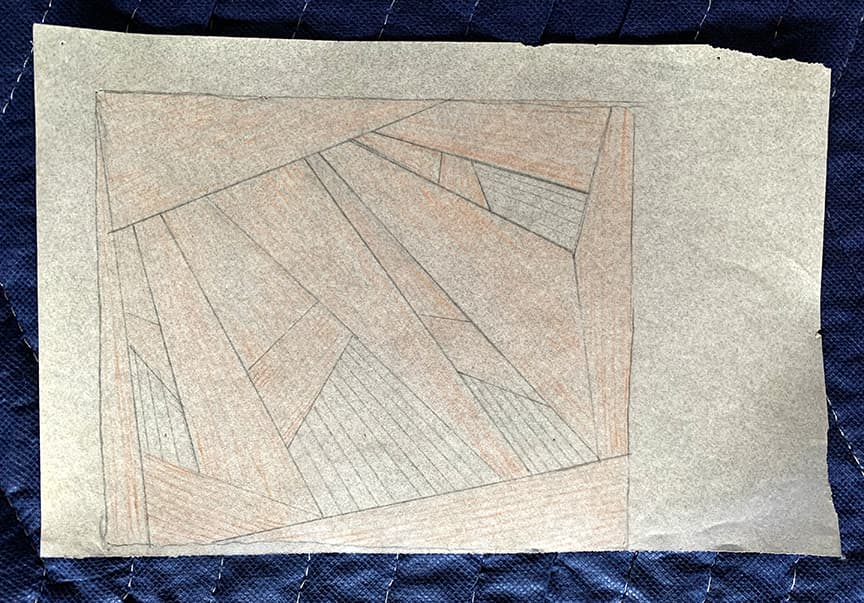

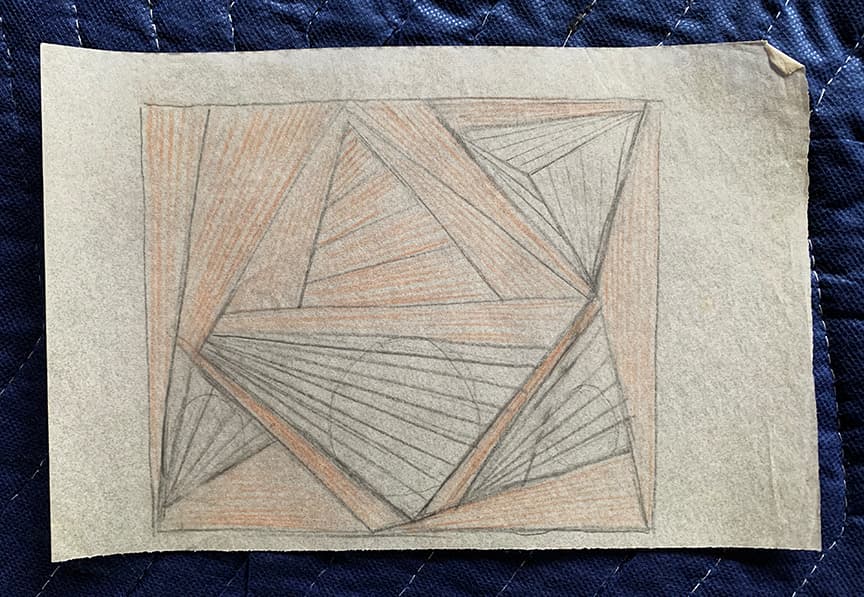

These drawings, believed to be sketches related to the music room grill, echo the radiating and prismatic forms featured in the Bok fireplace and doorway – and its potential enhancement of the dynamic interiors.

This story is reminiscent of another playful battle of wills, this one between Esherick and Bert Kulp, the stonemason who helped construct the studio in 1926. In his own oral history recording, Esherick relays how he and Kulp went back and forth on the shape of the stones – Kulp always asking to cut the stones square, which would be far easier for layering the next course of stone as the walls went up, and Esherick always insisting that the stones remain rough and uniquely shaped. Once the carpentry began on the Studio, Esherick was occupied with the woodwork and Kulp – on his own for the last couple weeks of construction – went right back to cutting the stones square. As Esherick tells the tale (a recording of which you can listen to in our Tilted Tales Spotlight Talk) he delights in Bert’s stubbornness and exasperation at Esherick’s unusual demands, laughing and remarking “Oh, Bert was a wonderful guy.”

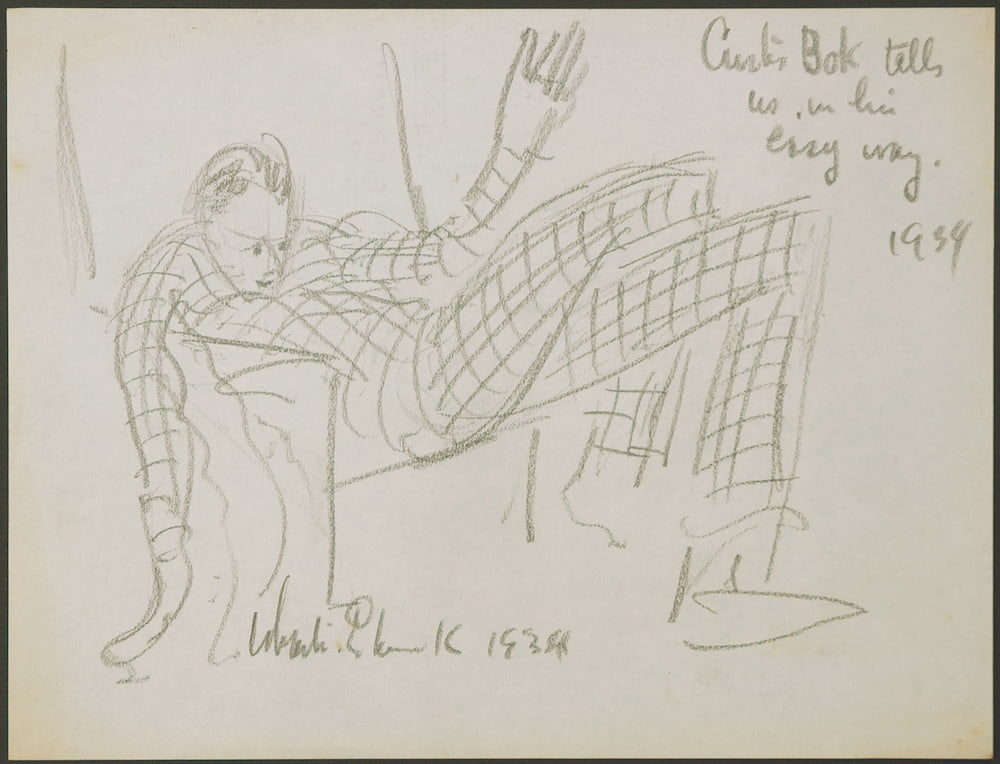

Wharton Esherick. Curtis Bok Tells Us in His Easy Way, Pencil on Paper, 1934. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection.

For Esherick and Curtis Bok, it seems their friendship weathered the large-scale project, from the difference in taste in the music room to the sticky business of money, fairly well. On completion of the endeavor, Bok wrote to Esherick that “Never in my wildest dreams did I think that it would be so beautiful – or cost so much.” For his part, Bok appears to have been careful to value Esherick as an artist. In one gesture of appreciation, Bok included a $5000 design fee for the music room, knowing that Esherick was often reluctant to bill accurately for his own time. This stands in sharp contrast to the Watson house, Esherick’s commission to design an entire home in upstate New York, which ultimately unraveled after being undervalued for his design work. Here Esherick and Bok maintained a warm relationship through their ambitious undertaking at the house in Gulph Mills, one that gave the world a stunning interior space like no other.

» Read Joseph Esherick’s Recollections of his Uncle Wharton

» View additional images of the Bok Interiors

Post written by Deputy Director of Operations & Public Engagement Katie Wynne.

January 2024