Wharton Esherick didn’t like it when people came to his Studio wearing sunglasses. He wanted to see their whole expressions. Empathy was important to the work he did on commission. Time and again he befriended his repeat customers. The relationships he had with these patrons deepened over the years as they filled their homes with his sculptural furniture. Esherick knew he could make objects that they would love, because he knew them. A breakdown of human connection could spell disaster. Such was the case with the work he did for Michael Watson.

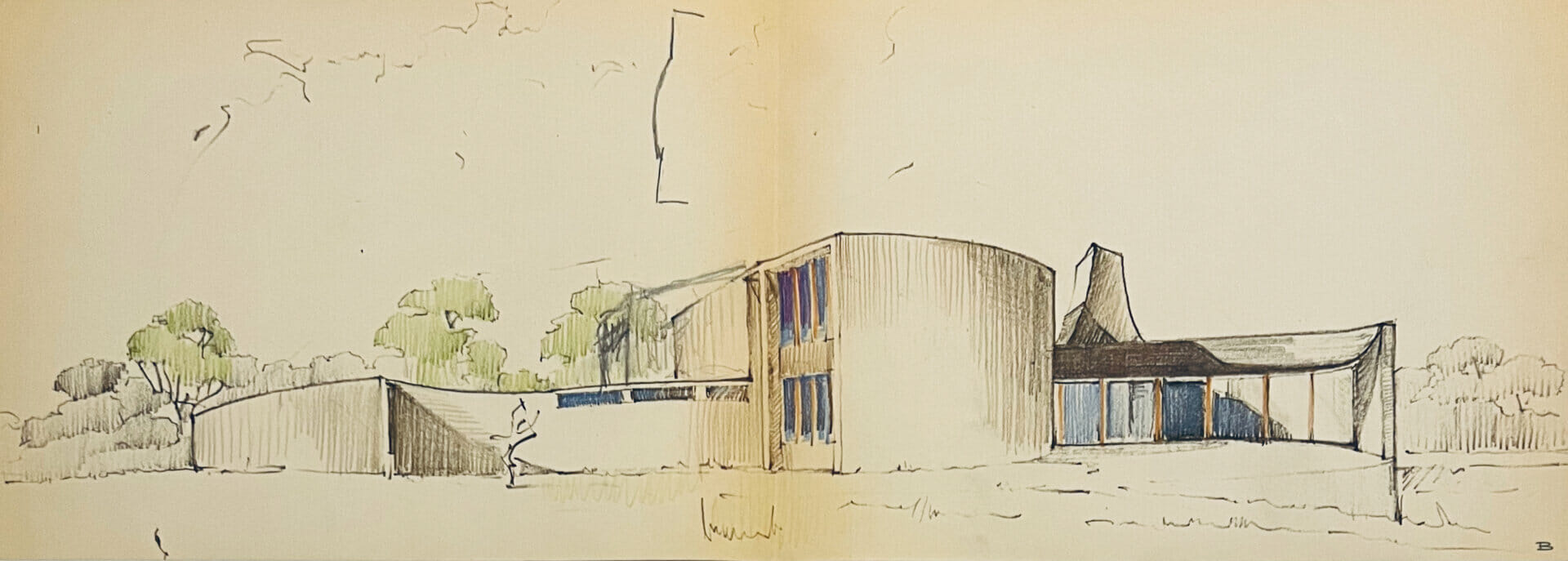

Wharton Esherick, designer. Sketch for Watson Residence, circa 1962.

Esherick first met Watson in 1961. A mutual friend, the renowned ceramist Frans Wildenhain, introduced them. Watson, an art collector and neuroscientist, was planning a new house for his family in Pittsford, New York, a suburb of Rochester. Watson was also an amateur woodworker. Admiring of Esherick, he traveled to Pennsylvania to visit his Studio. Upon seeing the artist’s self-built home and workspace, he decided that Esherick should design his house. The Watson Residence was Esherick’s first and only commission to plan a major building from foundation to roof.

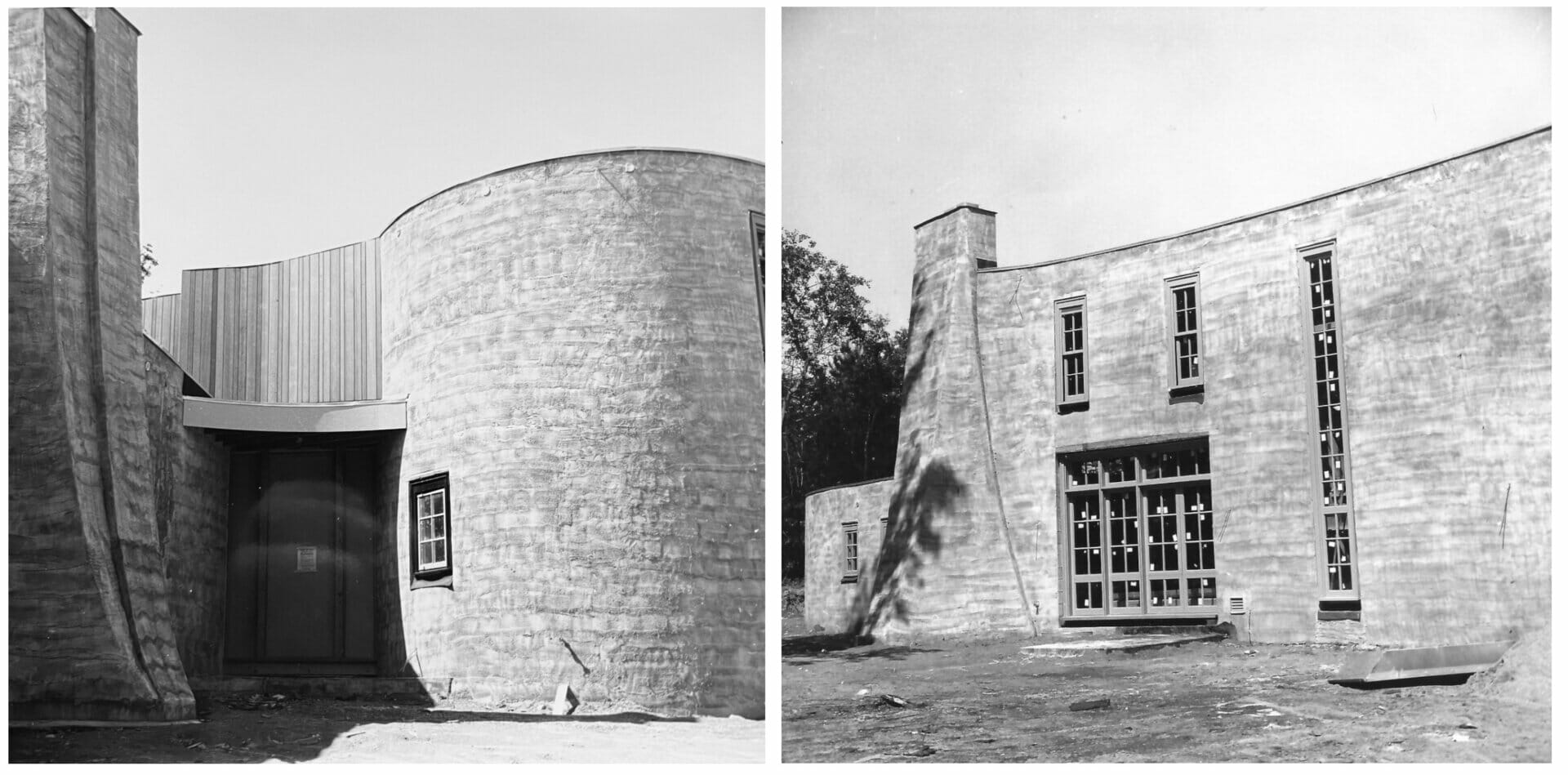

Watson Residence under construction, 1963.

Esherick’s background was in art, not architecture. He approached the Watson Residence as sculpture, dreaming up walls, ceilings, chimneys and windows as modernist abstract forms. The architects and builders whom Watson hired did the technical work of realizing these unique designs in concrete.

At the same time as Esherick was sketching plans for the house, he was also building Watson a staircase. When Watson had visited the Esherick Studio, he swooned over a red oak spiral stair that Esherick had made decades earlier. He asked Esherick to replicate the piece for him. Esherick agreed, sort of. He would build a variant on the design, but not copy it. He began with a scale model. Next, he and his workmen rough cut the stair parts from logs and stacked them to let the wood dry. Finally, they sculpted treads, column, stringer, and handrails, and assembled the staircase in their workshop.

Stack of rough shaped stair parts (treads) for the Watson Staircase, 1963.

At the start of these projects, Esherick and Watson were friends. Energized by the creative endeavors that united them, they proceeded without anything so formal as a signed contract. But, as the work progressed, the relationship went cold. Watson refused to pay what Esherick asked. On top of that, he threatened to reject the staircase, which he said was a low quality design. Most upsetting of all for Esherick, Watson stopped relating on a human level. Esherick wrote to him in a letter:

I believed our relationship was one of mutual trust—that I was engaged because of your confidence in what I could do for you, and that I because of your confidence would be reimbursed for my expenses. But along with this we had a friendly ease of communication. Yesterday’s experience was like a wall of ice. How do we melt it?

Detail, Watson Staircase assembled in Esherick’s workshop, 1963.

Detail, Watson Staircase assembled in Esherick’s workshop, 1963.

Esherick and Watson resolved their disputes through compromises brokered by others. Esherick settled for a reduced fee. Watson accepted the staircase. Architects oversaw the completion of the house, and the Watson family moved in. Esherick continued to reach out to Watson about getting access to the residence in order to photograph his sculptural creations. He appealed to his one-time client as a friend. But Watson was done relating. He had, in effect, put on his sunglasses.

Interior of Esherick’s workshop with Watson Staircase, 1963.

Written by Director of Interpretation and Research Holly Gore

October 2022