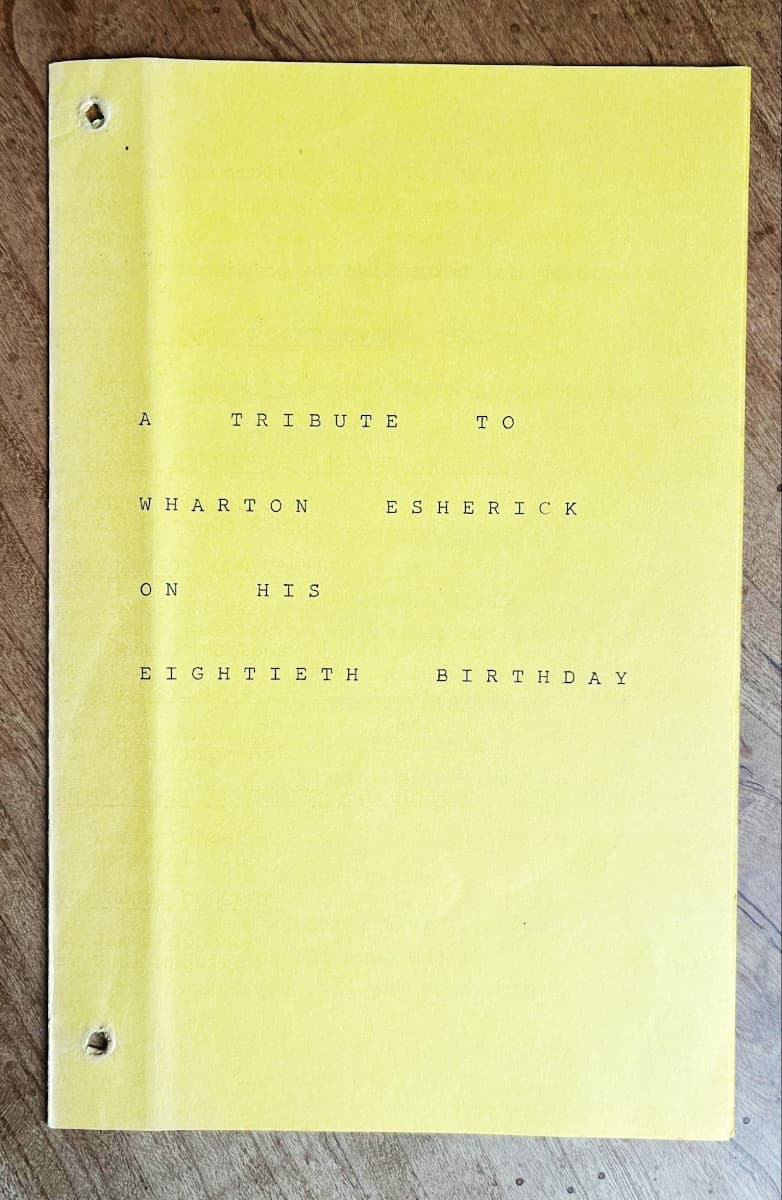

Fig 1: Pamphlet for Wharton Esherick’s 80th Birthday Party: “A Tribute to Wharton Esherick on his Eightieth Birthday”

Wharton Esherick became an octogenarian on July 15, 1967. The artist had accomplished so much in his eighty years that there was more than just a birthday to celebrate. Friends and family marked the milestone by throwing Esherick a birthday bash large enough that materials from the celebration have left a remarkable footprint in the museum’s archive. Three folders worth to be exact. They are filled with letters, notes, telegrams, and birthday cards—both commercial and handmade—from friends, clients, and colleagues. This cache of material gives up a glimpse into a celebration for the ages.

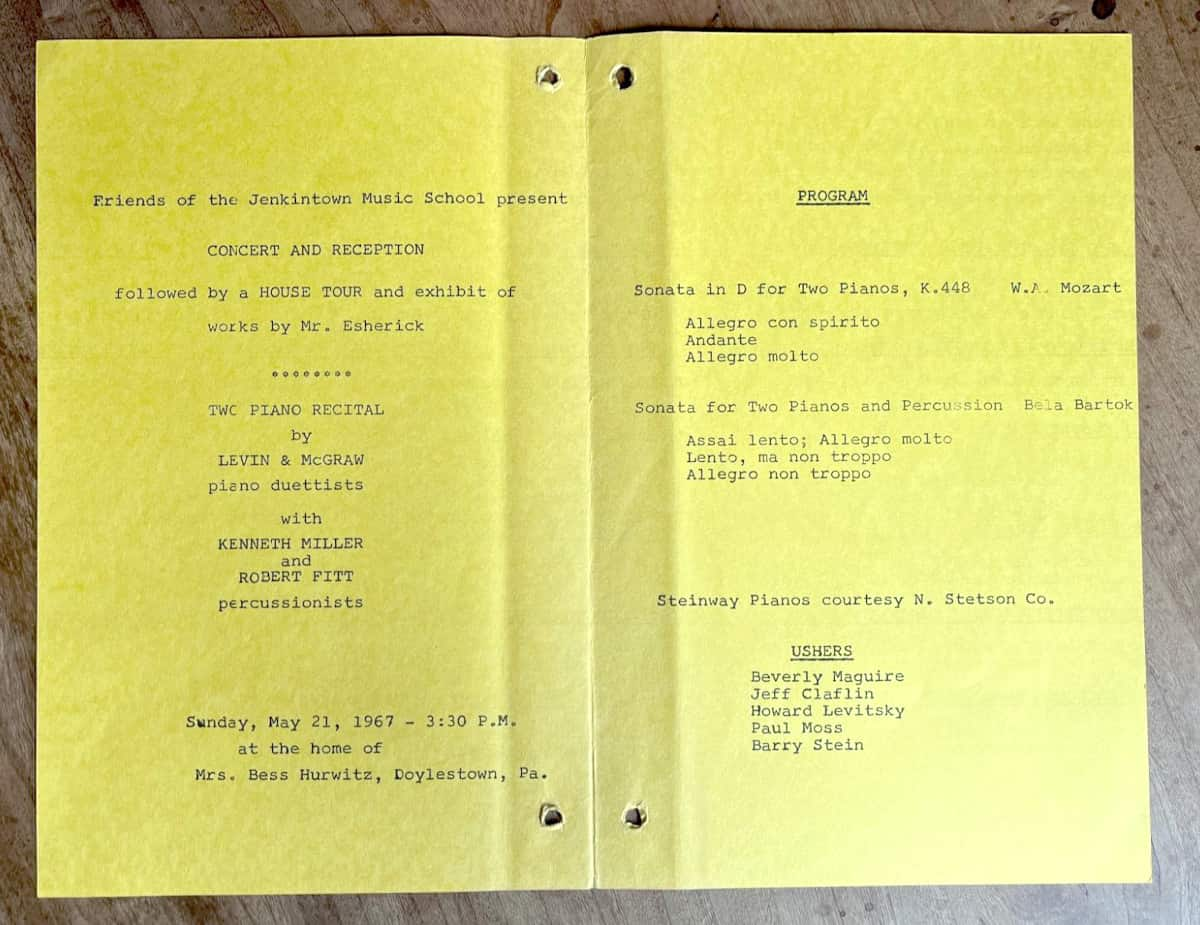

The party was formal enough that bifold yellow cardstock programs were printed for the occasion. Esherick’s party was given the title “A Tribute to Wharton Esherick on his Eightieth Birthday” (figs. 1 and 2). The afternoon featured a two-piano recital by the Jenkintown Music School of Mozart and Bartok sonatas with ushers present to show guests to their seats. The recital was followed by a reception, exhibition of Esherick’s work, and a tour of Bess Hurwitz’s home in Doylestown, where the party was hosted.

Bess Hurwitz was one of Esherick’s long-time clients. When she and her husband Nathan retired to Doylestown in the early 1950s, Esherick outfitted their home with the help of his shop hands, Bill MacIntyre and Horace Hartshaw. These three successfully converted what was originally a three-car garage into a functional home. They built closets, bookshelves, interior walls, and without needing to be asked, Esherick painted the walls his signature layered blue (presumably akin to the Studio’s front door or the surface of his garden horse sculpture). Bess Hurwitz recalled in her 1983 oral history interview that “if you’d just let Wharton do what he wanted, he could do anything,” and emphasized the artist’s generosity.

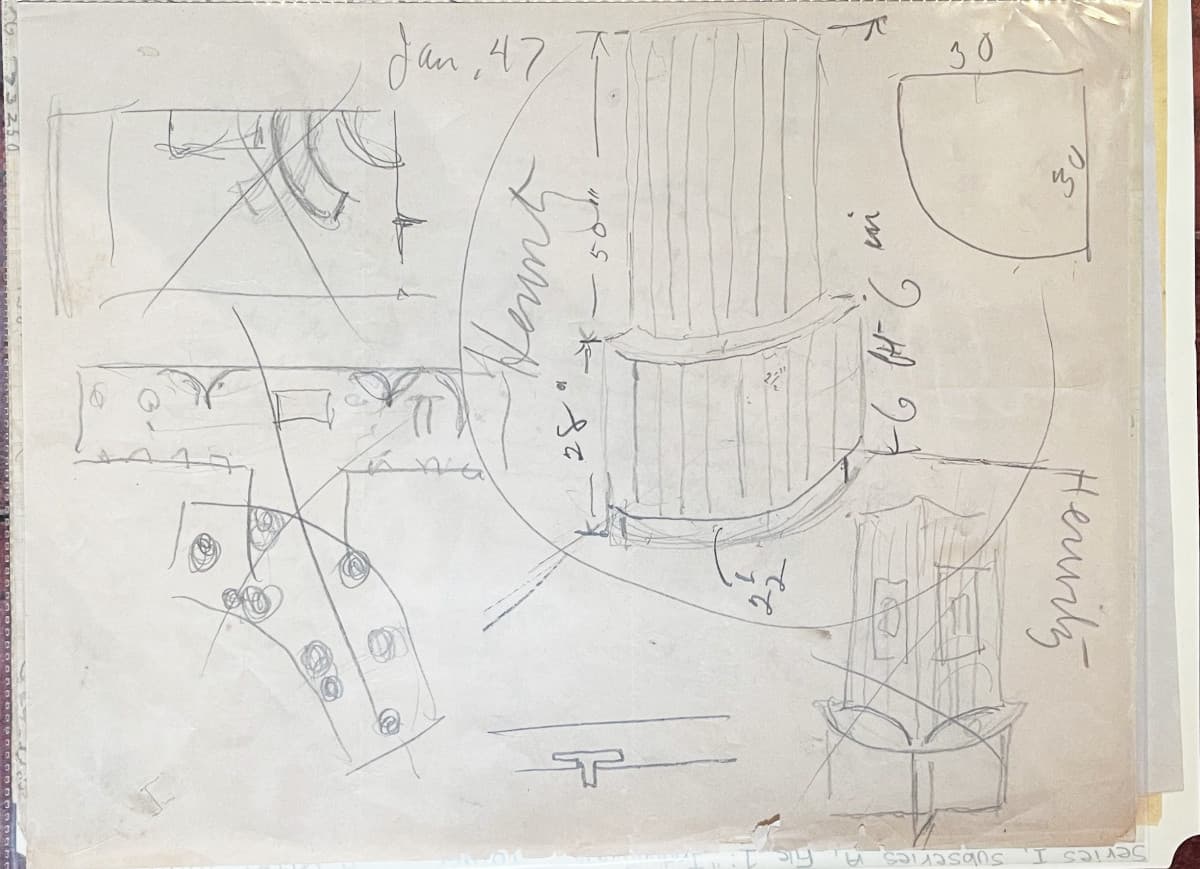

Esherick’s relationship with the Hurwitz family dated back to the late 1930s, when Miriam Phillips introduced the artist to Bess and Nathan. Bess Hurwtiz spent a significant amount of time in Esherick’s studio, and she recollected that Wharton never seemed to mind. He made several things for their apartment on 6th Street in Philadelphia, starting with a desk Bess commissioned for her husband (fig. 3). Many more commissions followed, such as a blanket chest, a cabinet to hold their Danish porcelain, and a case for their speakers that Wharton called a “noise box.” Bess and Nathan Hurwitz even purchased Esherick’s five-sided World’s Fair table in 1948.

Like many of his patrons, the Hurwitz couple were subject to Esherick’s antics. Bess shared a story about returning to their Philadelphia home from a vacation in Europe to find their store-bought furniture had all but disappeared. Wharton had modified them with his personal touch. The antics did not end there. When delivering a cabinet Bess commissioned for their Philadelphia apartment, Esherick showed up with a table the couple had never seen before and had not ordered. Esherick brought it to replace their dining table which Bess felt was never quite adequate for them. They all ate dinner that night on this new table. It stayed in their Philadelphia apartment until they moved in the 1950s. Like many of Esherick’s patrons, they took the surprise piece and never discussed the price. Thus, hosting the birthday party in her Doylestown home was undoubtedly a way for Bess Hurwitz to show her appreciation for Wharton, his generosity, and their over twenty-five-years of friendship.

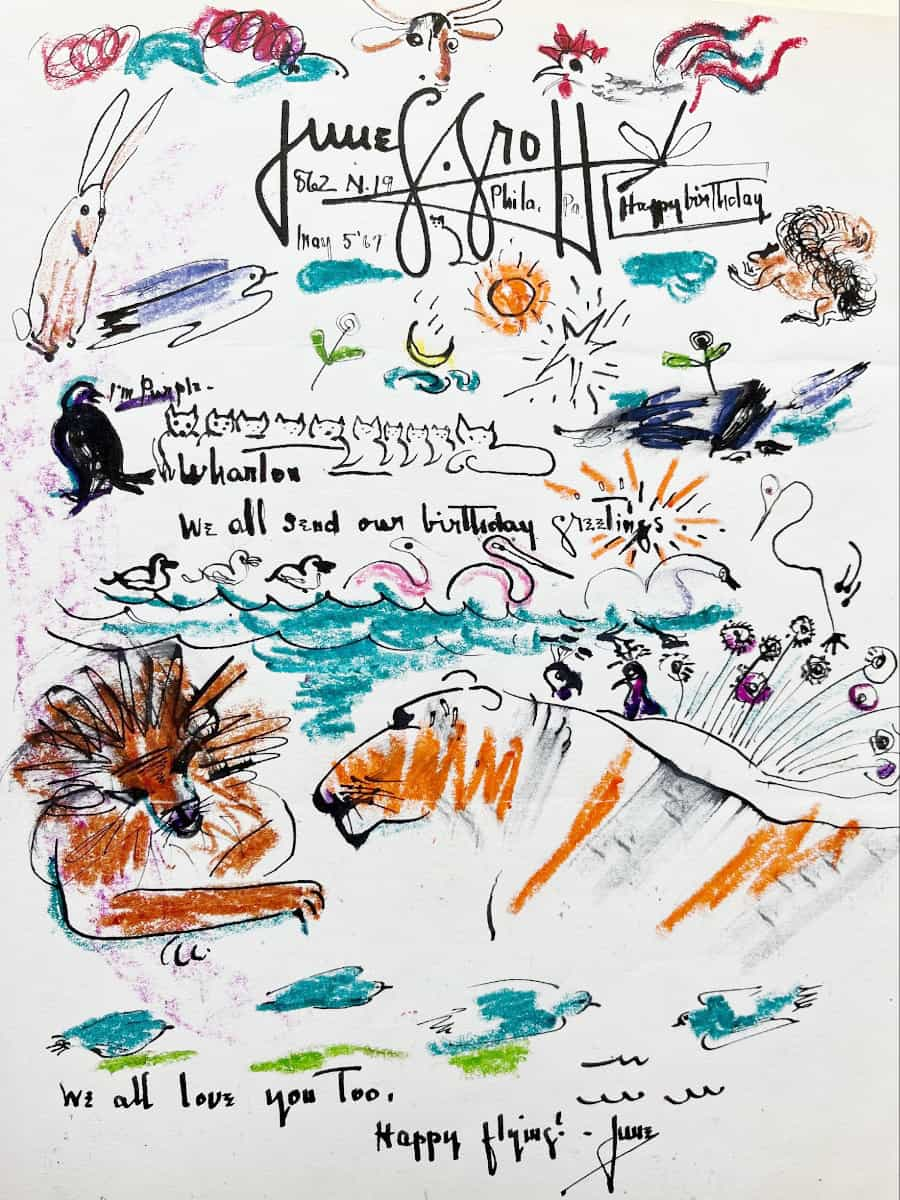

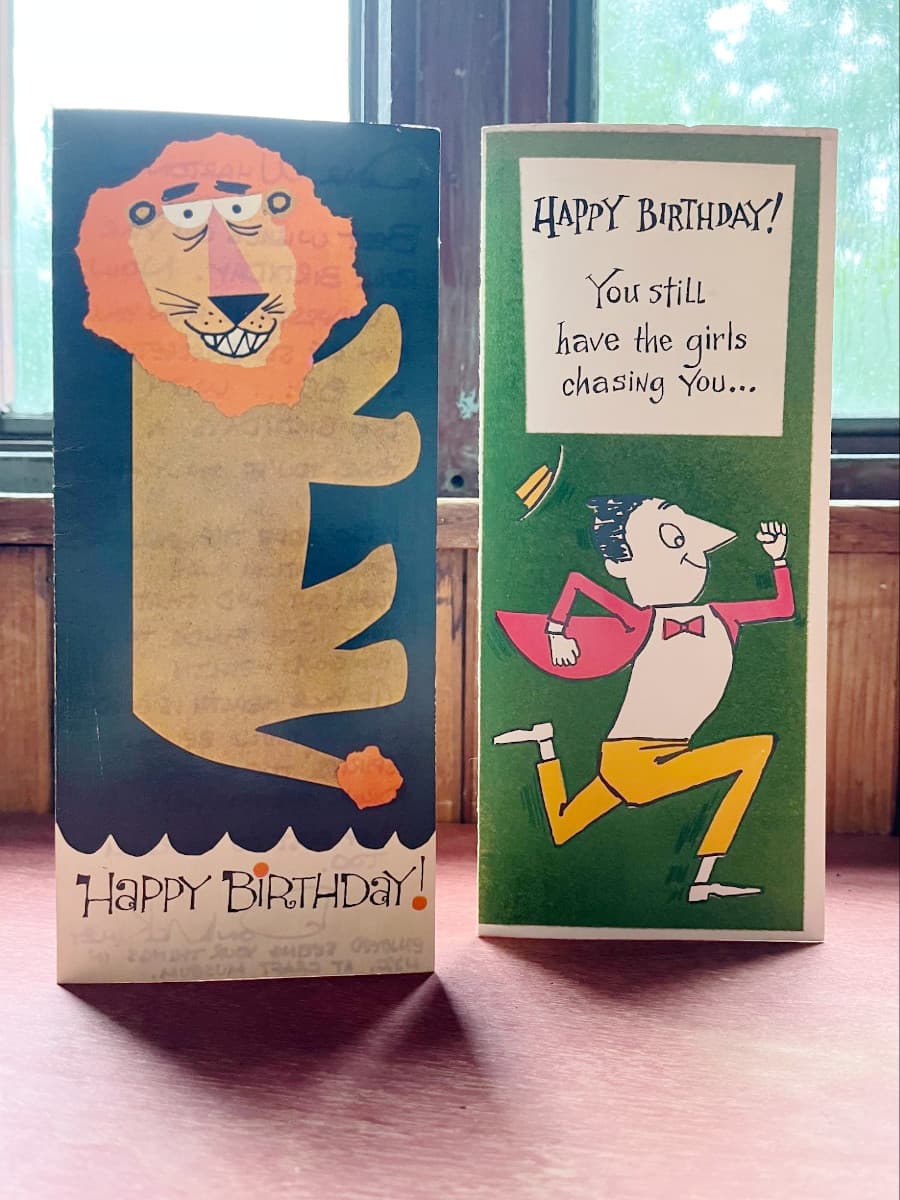

Party guests showed their appreciation for Esherick with notes and birthday cards (fig. 4). Friend and textile artist June Groff drew a colorful, whimsical birthday card featuring lions, tigers, pelicans, and other creatures that complement Esherick’s studio full of animal sculptures. Groff signed the card “We all love you… Happy flying” (fig. 5). Others, like the modernist photographer and friend, Marjorie Content, took the opportunity to reflect on her decades-long friendship with Esherick. Content recalled meeting Esherick for the first time on the Hudson in the early 1920s through her then neighbors, Henry and Bessie Poor. Roughly forty years later, Content commended the almost-eighty-year old’s ever-youthful outlook, noting how “many older people develop a tendency to look backwards and emphasize the past. Now Wharton – his focus and interest are on what lies ahead.”

Fig 5: Commercial birthday cards from Don McKinley (left) and the Fischers (right) to Wharton Esherick. May, 1967.

Sam Maloof echoed these sentiments in a Western Union telegram sent across the country from Alta Loma, California. The younger generation of sculptors and woodworkers also admired Esherick’s forward looking perspectives. ”Dear Wharton,” it reads, “my sincere congratulations your contribution to the arts have been and are today an inspiration to those who know your work and especially to those of us who have had the privilege of knowing you personally” (fig. 6).

There is one big question surrounding Esherick’s 80th birthday that the archive cannot quite answer. Why did his eightieth birthday take place almost a full two months early on the third Sunday in May? At the beginning of 1967 Esherick suffered a stroke that hospitalized him for a week. This was the start of a decline in his health and his workload. It seems as though there was reason enough for spirits to be lifted during this time. Also possible was a concern that Wharton might not live to see his 80th birthday, although no sentiments of that nature are recorded. To the contrary: friends writing to Wharton after a visit in February say it was “a surprise and joy” to see him as his “true, uncompromising self… expressing W.E.” despite his “so-called” stroke. Considering the timing of the party, it likely celebrated Esherick’s triumph of his health-scare, his impending birthday, and the legacy that was forming on his heels.

This July marks Wharton Esherick’s 136th birthday. Our staff, volunteers, and friends of the Esherick both old and new celebrated in the 1956 Workshop to mark the occasion. To honor Esherick’s legacy, we invited woodworkers, a textile artist, and a printmaker to do demonstrations, as well as the kindred organizations Rose Valley Museum and Historic Yellow Springs.

The Wharton Esherick Museum has rich archives that include Esherick’s personal and business papers, his correspondence with leading figures in American modernism and the studio craft movement, as well as an extensive oral history collection. The archives are open to researchers by appointment. For more information, please contact Research Director Holly Gore at [email protected]

Post written by Public Programs & Collections Manager Ethan Snyder

July 2023