In the biography Wharton Esherick: The Journey of a Creative Mind, Mansfield Bascom notes that Esherick was introduced to the writings of Henry David Thoreau by Harry Attmore. Attmore and Esherick worked together at the Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, New Jersey. Attmore was the older of the two and a great influence on Esherick, exposing him to socialist and progressive thinkers and writers like Thoreau and Walt Whitman. Esherick had recently departed from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts when he worked for a time creating drawings to be used for the company’s poster designs. Before long, Esherick would be married and heading off to the Paoli countryside to begin his own experiment in living close to nature.

It’s hard to capture how much Thoreau’s writings influenced Esherick’s path to creating a life surrounded by and in step with nature. It seems reasonable to think those early texts shared by Attmore were part of a swirl of progressive and philosophical thought in the early 20th century as people – artists in particular – sought a return to nature. What we can say with more certainty is that Esherick continued to read and return to the works of Thoreau, and biographies about him, throughout his life.

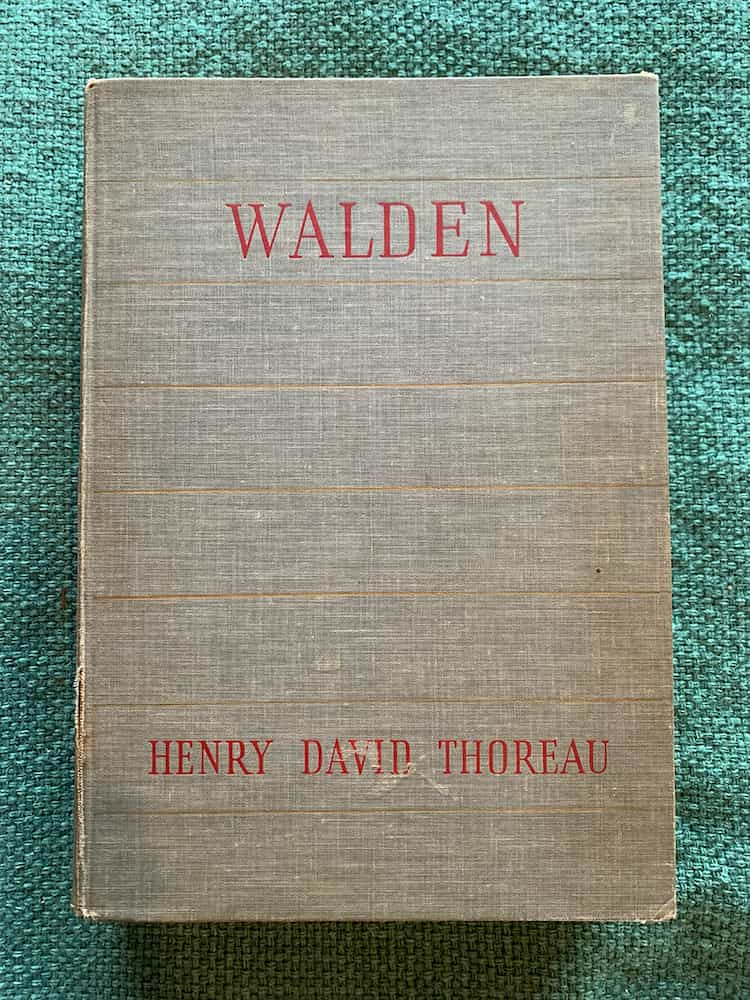

Esherick’s copy of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden

On the bookshelves above Esherick’s bed – in the company of texts by Esherick’s author friends Sherwood Anderson, Ford Madox Ford, and Theodore Dreiser, and the philosophical writings of Bertrand Russell – sits The Works of Thoreau, a 1937 publication edited by Henry S. Canby that includes the complete Walden as well as other selected texts. A second copy of Walden can be found at the foot of the bed and throughout the room we can find a dozen titles either written by or about Thoreau in Esherick’s collection.

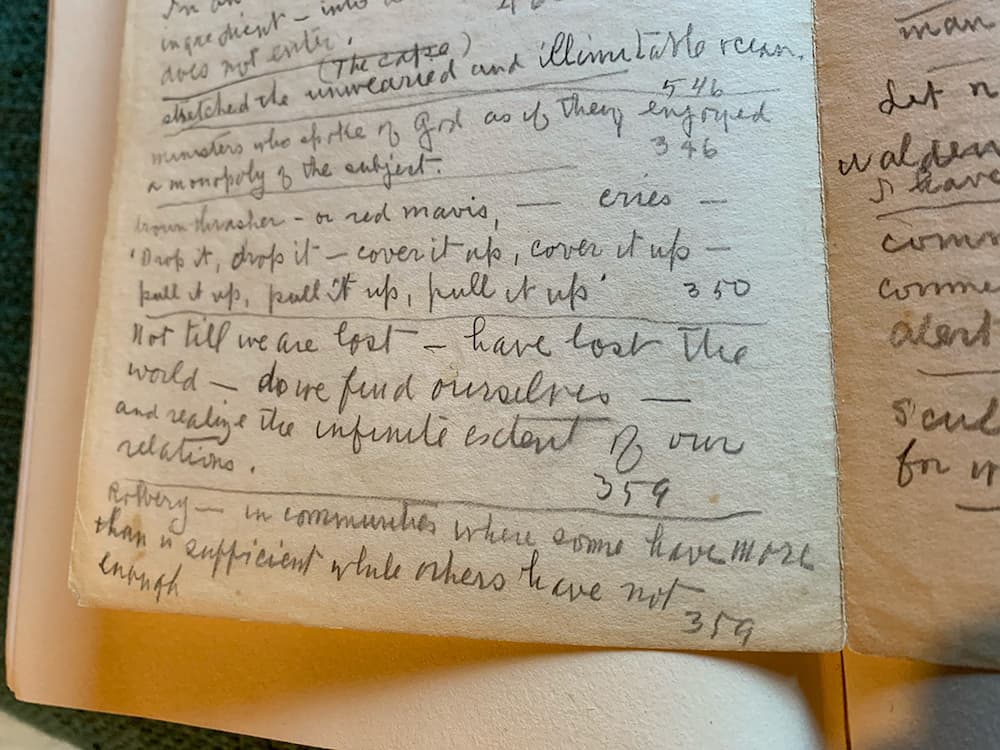

Tucked into his copy of Walden are Esherick’s notes – loose slips of paper listing full or paraphrased passages and page numbers. Esherick was not exactly a robust notemaker in his books, so it’s remarkable that his notes on Thoreau are more substantial than any other author in his library. Thoreau’s observations on life lend themselves perfectly as guiding principles to be plucked off the pages. Esherick’s compiled notes range in topic from how best to spend one’s life and what actions give it meaning to the observations of songbirds.

Handwritten notes by Esherick found inside his copy of Walden

A few selected notes here offer insight into the ideas and passages that resonated with Esherick:

Notes from Walden-

“Not till we are lost, in other words not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.”

“I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life in which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.”

“If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.”

“As I did not teach for the good of my fellow-men, simply for a livelihood, this was a failure.”

“A great field of ice has cracked off from the main body. I hear a song sparrow – olit, olit, olit – chip, chip, chip, che char – che wiss, wiss, wiss. He too is helping to crack it.”

“Near at hand, upon the topmost spray of birch, sings the brown thrasher – or red mavis, as some love to call him – all the morning, glad of your society, that would find another farmer’s field if yours were not here. While you are planting the seed, he cries – ‘Drop it, drop it – cover it up, cover it up – pull it up, pull it up, pull it up.’”

“The poor rich man! All he has is what he bought.”

–From A Week On the Concord and Merrimack Rivers

“Essentially your truest poetic sentence is as free and lawless as a lamb’s bleat.”

–From Selections from the ‘Journal’

View of Esherick’s Studio dining room

Many of the passages echo familiar themes in Esherick’s own biography, whether his well-known aversion to formal teaching, or the admiration he felt for the songbirds that surrounded his hillside studio. A life lived in close observance with nature. The life of a non-conformist. Esherick’s ideals seem reaffirmed in Thoreau’s words.

Esherick likely explored Thoreau’s ideas in conversation with friends as well. Esherick kept a list of books he loaned to friends, on this list he notes a few Thoreau titles lent to his neighbor and friend Lachlan MacLachlan. Esherick’s Thoreau collection includes The Living Thoughts of Thoreau, presented by Theodore Dreiser, published in 1939. Dreiser and Esherick became close friends after meeting at the Hedgerow Theatre in 1924. Esherick made significant notes on this book as well, and it provides another indication that Thoreau’s philosophies resonated among Esherick’s circle.

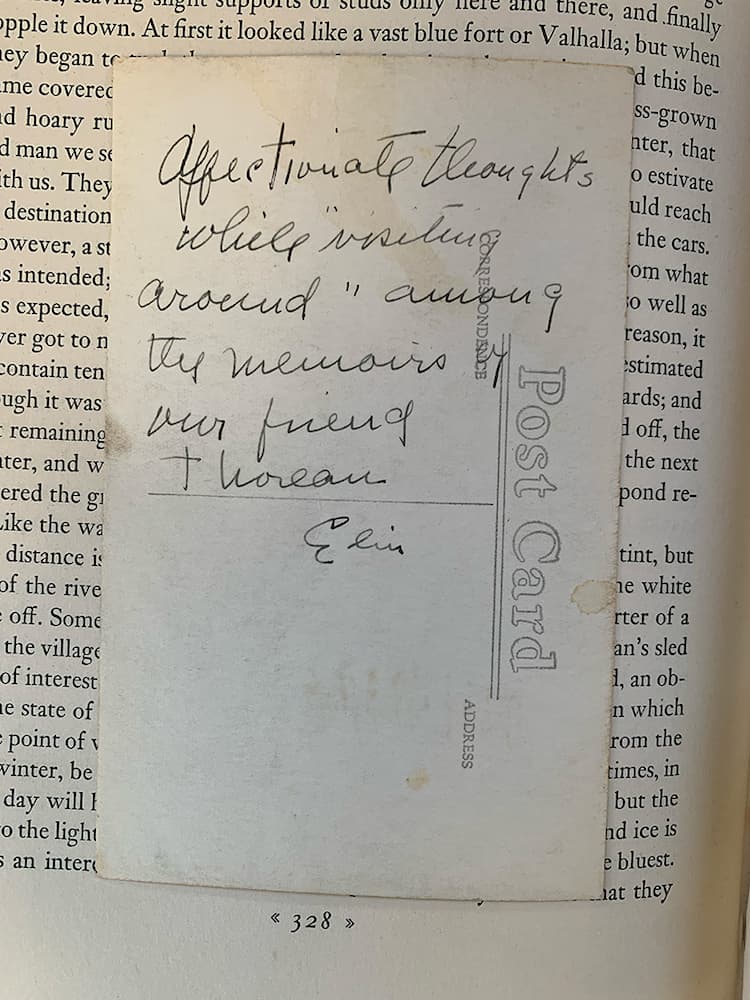

Note from Elin and Olaf Rove written on the back of a postcard featuring a portrait of Thoreau

Tucked into Walden, alongside his notes, is a postcard – a portrait of Thoreau with a note on the back from Elin Rove. Elin and Olaf Rove were dear friends of Esherick who commissioned numerous works for their home, a renovated barn in Falls Church, Virginia. They appear repeatedly on Esherick’s loaned books list leading us to wonder if the postcard – which is not addressed – was a thank you note of sorts for a lent copy of Walden, or perhaps a keepsake from a trip to Thoreau’s hometown of Concord, Massachusetts. Either way, Elin’s note sums up the warmth that they both shared for Thoreau’s writings:

“Affectionate thoughts while “visiting around” among the memoirs of our friend Thoreau – Elin.”

» Watch Spotlight Talk: Unpacking Esherick’s Library

Post written by Deputy Director of Operations & Public Engagement Katie Wynne.

February 2024