In music, a “berceuse” is a lullaby, a composition with a rocking accompaniment and a soothing refrain. Wharton Esherick’s Berceuse (1923) is a soapstone sculpture where the mood is as mournful as it is lulling, and the line between sleep and death is thin. The artwork portrays a woman who holds an infant close to her downturned face. The child looks newborn, its soft body nestling into a pair of adult hands. Wharton Esherick created Berceuse for his wife, Letty Nofer Esherick, to memorialize their daughters Jane and Anne who died in infancy.

Wharton Esherick, Berceuse, 1923. Soapstone, walnut, metallic pigment. Wharton Esherick Museum. Wharton Esherick made Berceuse for Letty Nofer Esherick, his wife. After the Eshericks’ marital separation, Letty owned the piece. It now hangs in the Esherick Studio dining room.

Wharton Esherick, Berceuse, 1923. Soapstone, walnut, metallic pigment. Wharton Esherick Museum. Wharton Esherick made Berceuse for Letty Nofer Esherick, his wife. After the Eshericks’ marital separation, Letty owned the piece. It now hangs in the Esherick Studio dining room.

Detail of Berceuse.

Detail of Berceuse.

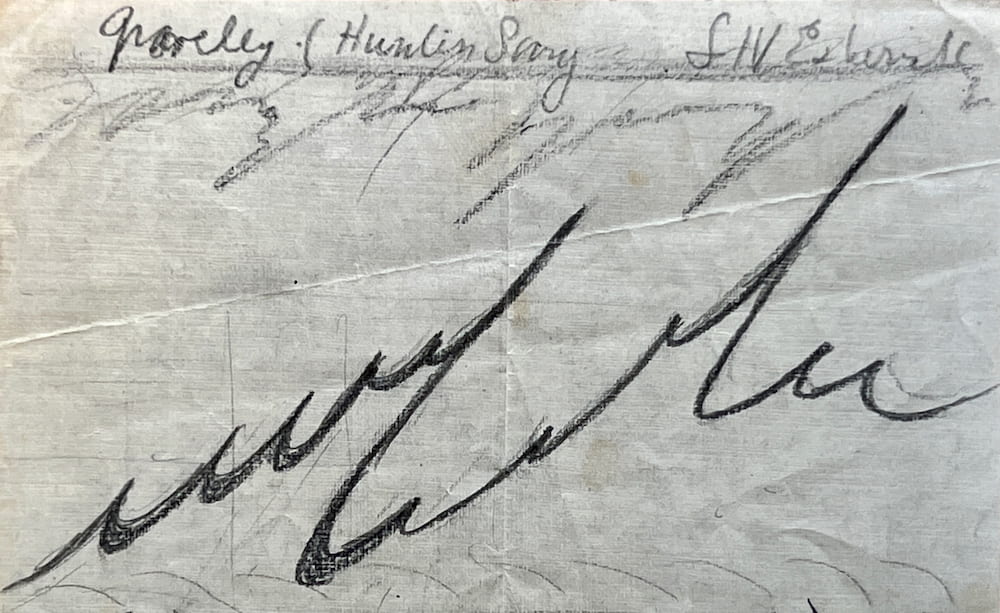

In some ways, Berceuse resembles a Madonna and Child. Its mother-and-baby imagery, complete with a shimmering gold halo, makes an emphatic nod to Christian art. But the gestures that Esherick carved into the stone set his portrayal apart from most Madonnas, who present to the world a child who is vibrant, alert, and at least partially upright, whether seated or standing. According to Esherick, gesture was the origin of Berceuse. In an interview, he said that that his first sketch for the piece was a drawing he had done to a musical composition:

Berceuse was done when we were up in the Adirondacks at Ruth Doing’s. Robert Emont did a piece of music and he called it “Berceuse.” And while he was doing it, I was making the drawing to the music. And then I came and made the Berceuse out of soapstone.

–Wharton Esherick, oral history interview, 1968-1970

Dancers at the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics, circa 1920. The photograph is from an Esherick family album and was probably taken by Delight Weston. Wharton Esherick Museum.

Dancers at the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics, circa 1920. The photograph is from an Esherick family album and was probably taken by Delight Weston. Wharton Esherick Museum.

There are several points in this recollection that bear explanation. First off, the mention of “Ruth Doing’s” “up in the Adirondacks” refers to a dance camp where Wharton, Letty, and their children were regular summer visitors in the 1920s and 30s. Letty was the dancer in the family. She had a long involvement with a form of modern dance called “rhythmic dance,” or “rhythmics.” Therapeutic at its core, rhythmic dance was designed to benefit the dancer, as opposed to being a performance medium for entertaining an audience. In the early twentieth century, rhythmics was popular among artists, dancers, health and wellness advocates, and teachers in progressive schools. The dance camp where Wharton Esherick made Berceuse was the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics on Upper Chateauguay Lake, in northern New York.

Freedom was a major goal of Ruth Doing’s rhythmics: workaday schedules, unexamined conventions, confining shoes and undergarments, restrictive social mores, and the small, square spaces of city life all had to go. In their place were self-expression and reconnection with the rhythms of the natural world and human emotion—itself considered to be a force of nature. Rhythmics was interpretive in that dancers used their bodies to materialize the movements of natural phenomena like wind, waves, and planetary rotation. They did not so much keep time to the classical music that the camp pianist played, but rather, gave physical form to the emotions that it brought forth.

Letty Nofer Esherick and Wharton Esherick. Musical Design, 1920. Wharton Esherick Museum. Charcoal and pencil on paper. Letty made this drawing during an exercise in drawing to music. Wharton gave the piece a treatment that he used with his own sketches, refining, darkening, and sharpening select lines into a design that was suitable for woodcarving.

Letty Nofer Esherick and Wharton Esherick. Musical Design, 1920. Wharton Esherick Museum. Charcoal and pencil on paper. Letty made this drawing during an exercise in drawing to music. Wharton gave the piece a treatment that he used with his own sketches, refining, darkening, and sharpening select lines into a design that was suitable for woodcarving.

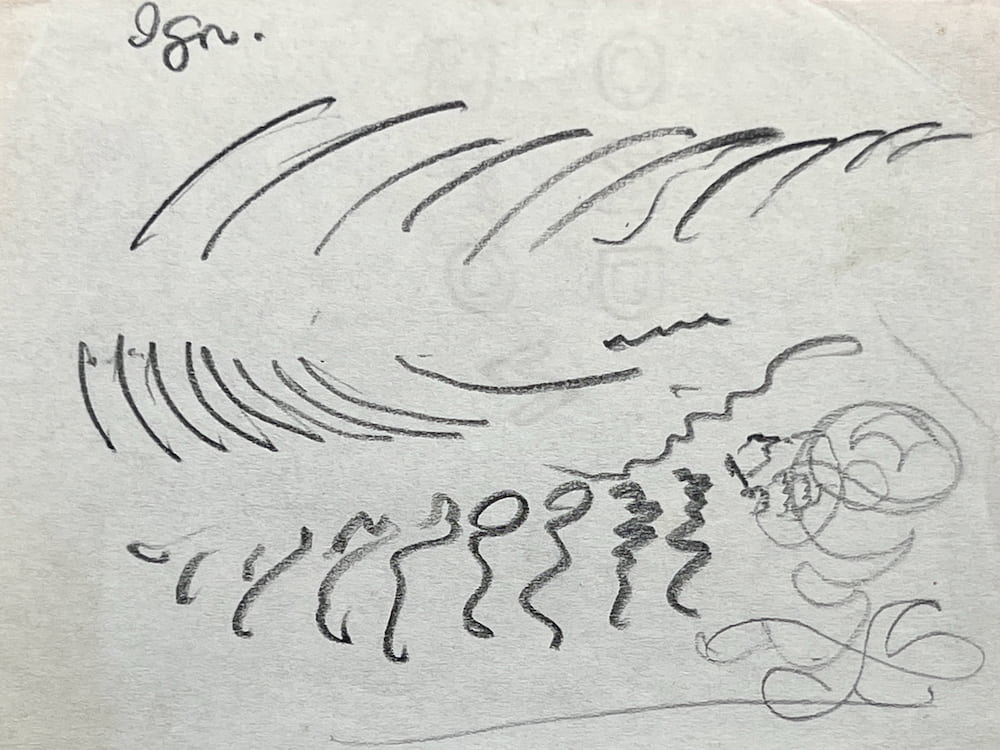

Another way in which Ruth Doing had her students interpret music was through line drawing. For this exercise, she instructed participants to empty their minds of any preconceived ideas about what they were about to sketch. As music played, they would draw a line on paper that was an extension of the rhythms, melody, and feelings of the sounds that flowed through their bodies. In this way, the musical drawings related to the interpretive gestures of rhythmics.

The Wharton Esherick Museum has in its collections around fifteen musical sketches. Some of these are clearly identified as having been created at the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics. A small, paper envelope holds a series of abstract designs that Wharton Esherick created from sketches by campers who partook in the musical drawing exercises. Each design is labeled with the name of the person who drew it, and the musical composition that they interpreted. Esherick synthesized these abstract, expressive, linear patterns into a decorative border for a camp table. (For an account of this and other Esherick camp tables, see our March 2024 blog post).

Wharton Esherick. Musical Drawing Labeled “Igor”, circa 1920s. Charcoal on paper. Wharton Esherick Museum.

Wharton Esherick. Musical Drawing Labeled “Igor”, circa 1920s. Charcoal on paper. Wharton Esherick Museum.

Other musical drawings in the Museum collections have far less documented context. One such artwork, a sketch labeled only with the single word “Igor”, begs the question: Did Esherick make this notation in reference to the Russian composer, Igor Stravinsky? Another work in the Museum collection. Zhar-Ptitsa (circa 1924), suggests that he did.

Wharton Esherick. Zhar-Ptitsa, circa 1924. Poplar, iron, paint, metallic pigment. Wharton Esherick Museum. The carving now hangs in the Esherick Studio. Its original location was in another building, an early workspace that Esherick used, where it served as a furnace grille.

Wharton Esherick. Zhar-Ptitsa, circa 1924. Poplar, iron, paint, metallic pigment. Wharton Esherick Museum. The carving now hangs in the Esherick Studio. Its original location was in another building, an early workspace that Esherick used, where it served as a furnace grille.

Zhar-Ptitsa is a circular grille carved in poplar, fitted into an iron ring, and painted red and gold. The carving within the circular rim depicts a fantastical animal of many names—firebird, phoenix, in French, oiseau de feu, and in Russian, zhar-ptitsa. In an interview that Esherick gave to a newspaper reporter he was explicit in linking his Zhar-Ptitsa to Stravinsky’s famous ballet and orchestral concert work of the same title. The reporter writes that Esherick had been touring him through his workspace, when he pointed to the artwork and explained:

That’s my Zhar-Ptitsa…. That’s Russian for “Fire Bird”—that’s what Stravinsky called his “Oiseau de Feu” in his own tongue.

–Wharton Esherick, newspaper clipping, 1925

Did the arcing, curlicued feathers of Esherick’s firebird derive from the similarly exuberant lines that are in the musical drawing marked, “Igor”? We may never know. But one thing that is certain is that during the time when Esherick carved Zhar-Ptitsa, his work attained new levels of emotion and musicality—in this case the exhilaration of rising up.

Despite its wealth of context, Berceuse also invites questions. As of now, no drawing has been found that can be explicitly tied to the sculpture. So then, what was the quality of the musical lines that Esherick drew and worked into the piece?

To my eye, the gestural qualities of Berceuse come across more clearly in a cast bronze version of the artwork than they do in the soapstone original. This is in part due to the simplicity of the maple backboard on which the bronze Berceuse is mounted. Minus the heavy symmetry of the walnut mount with its radiating halo, other, quieter movements come across.

Wharton Esherick, Berceuse, sculpted 1923, casting date unknown. Bronze, bird’s-eye maple. Wharton Esherick Museum.

Wharton Esherick, Berceuse, sculpted 1923, casting date unknown. Bronze, bird’s-eye maple. Wharton Esherick Museum.

Because a berceuse is, by definition, a lullaby, I was first inclined to find in the sculpture a soothing, back-and-forth rhythm. And indeed, the arc of the woman’s hands is angled slightly off-kilter in a way that suggests a cradle that has tipped one way and is about to rock back the other. But there is another gesture within the overall composition that strikes me the most: compression. The woman holds the child so very close to her face, which collapses into the baby’s belly. Her hands cross in a scissor motion, motioning inward to the middle of the artwork. The slightest indication of a cloth hood encircles her bowed head, furthering the sense of constriction, as if grief were a physical entity that closes in on the griever.

Berceuse and Zhar-Ptitsa are two examples of Wharton Esherick’s early ventures into sculpture. Each is a gesturally animated take on a familiar subject: Berceuse is a mother and child, Zhar-Ptitsa a firebird; Berceuse sinks into grief, Zhar-Ptitsa rises. With music related titles and historic background relating them to musical drawing, they are indicative of an era when Esherick set himself to transforming the fleeting, emotional experience of music into lasting physical communication of emotion.

Post written by Holly Gore, Director of Interpretation and Associate Curator

May 2024