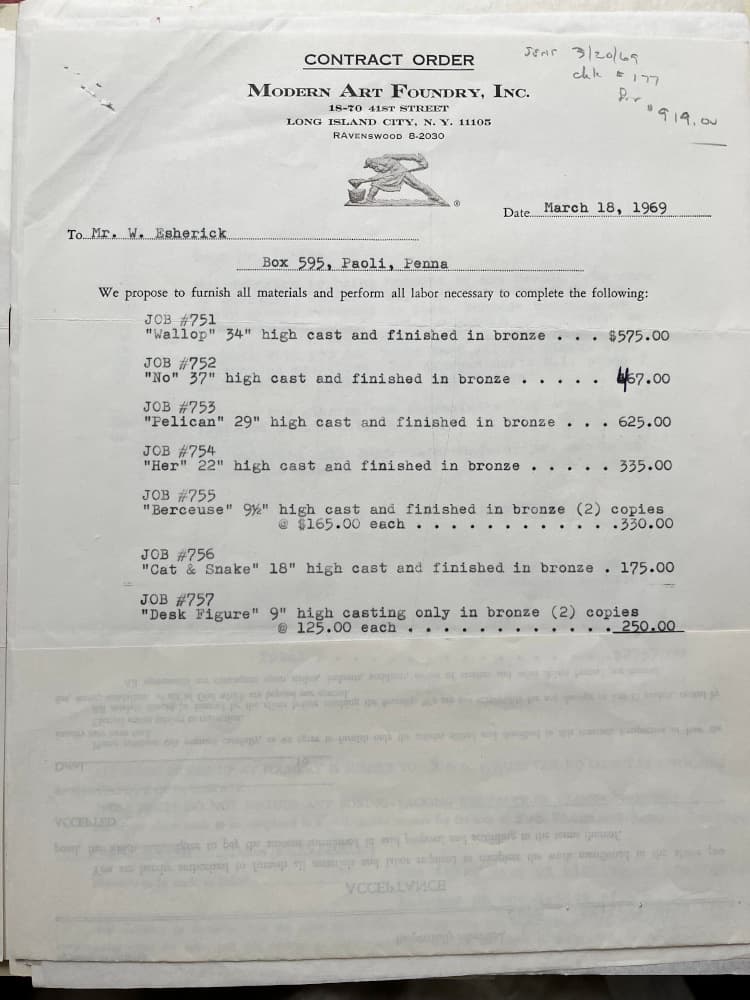

If you know one thing about Wharton Esherick, you know he worked with wood. At the Museum, we know Wharton quite well through his work in domestic woods like oak, cherry, and walnut as well as tropical woods like mahogany, padauk, and cocobolo. However, visitors to the Studio are first greeted outside the lower entrance by an object decidedly not wooden. Instead, a cast bronze pelican sculpture welcomes visitors as they enter the Studio’s main gallery. What might we learn about Wharton Esherick by turning toward a material other than wood? What might we learn about the artist through metal? At the Museum, we steward several of Esherick’s sculptures cast in bronze and aluminum, as well as professional correspondence with the Modern Art Foundry in Astoria, Queens from the 1960s. While our records pertaining to the Modern Art Foundry are seemingly mundane business documents, through them we can learn some interesting things about Wharton Esherick!

For one, Esherick preferred the lost-wax casting process, and specifically the Modern Art Foundry’s way of executing it. As the foundry’s services could begin from the original sculpture, there was no need for Esherick to meticulously recreate a sculpture in plaster. Esherick had turned down a solicitation from the Bedi-Rassy Foundry in Brooklyn after learning they needed him to supply a plaster model. While this meant that Esherick would leave the work of casting to the experts, this also meant that Wharton had to clean up the sculptures after they were returned from the foundry in Queens. Cleaning these pieces was especially important as clients often lent their sculptures back to Esherick so he could have them cast. The way Esherick complained to the foundry’s president John Spring about the amount of work it took to clean the sculptures of plaster before returning them to his clients makes one wonder whether it was the foundry’s responsibility to have done so.

Left: Plaster piece mold for Esherick’s 1942 sculpture Her.

Right: Wharton Esherick, Her, bronze casting after 1942 original.

Something else we can learn about Wharton Esherick is that he sincerely cared for his clients but did not care for the realities of working with a popular art foundry business. As Esherick often had to borrow sculptures back from clients for casting, he necessarily played two roles when working with the Modern Art Foundry: an artist having his sculptures cast and an advocate for his clients who were lending their possession for casting. Esherick acted as an advocate for his clients first and foremost. In one of the earliest letters we have with the Modern Art Foundry, Esherick tells Spring that his clients “will not take kindly to their [sculpture’s] absence for a long period.” As Esherick soon discovered, their work was gone for a long period. And that period grew. Spring reported two separate delays in work due to staff shortages, vacations, and other, nondescript reasons in an early batch of letters held in our archives. In total, the process took close to five months, and two more than estimated.

Correspondence from later in the 1960s shows that Esherick began to plead with Spring to give him more realistic timelines for the work and to ensure the original sculptures were returned to him as soon as the first piece molds were completed. This way, Esherick would not have to borrow sculptures from clients in service of another any earlier or longer than necessary. He asks Spring for specific dates: when would the casting process start? And when would the castings be finished? This way, Esherick could give specific dates to clients for when he would pick sculptures up and when he would return them. The whole business of working with a foundry, it seems, gave Esherick a headache. However much of a nuisance navigating the needs of clients and the realities of a foundry was, it did allow Esherick to sell copies of his work.

Working with the foundry also allowed Esherick to retain a copy of works he wasn’t ready to part with. For example, Morris and Robin Satinsky of Villanova, Pennsylvania purchased Wharton Esherick’s sculpture The Wallop in 1969. This Joe Louis inspired sculpture was originally made in 1945 and it had lived with Esherick’s in his studio ever since. Esherick was ambivalent about selling this sculpture when the opportunity finally arose. However, he agreed to sell it on the condition it would be cast first so that he could retain a copy of this sculpture that was clearly dear to him. A few months later, a shining bronze replica replaced the original black walnut. It is said that Esherick had this sculpture cast “so as to not lose an old friend.” The fact that he sold the sculpture for only $15 more than it cost to cast suggests it was more important for the artist to retain a copy than it was to make money by selling it. The casting cost $575 and the original was sold for $600.

We know that Esherick had sculptures and other objects cast in metal well before the 1960s and Esherick even worked metal himself on occasion. However, records of that work are scant. Thus, we’re left to ponder the objects and their stories. For example, Esherick learned how to forge iron at the blacksmith shop at the Central Manual Training High School. Esherick mentions in his oral history that some of this iron is in the Studio. We suspect “that little hook” he references is the one hanging unassumingly in the Studio kitchen. Esherick admits that he couldn’t have done this work without the “skillful man standing over [him] telling [him] where to hit” and that he “did all the hammering” himself! As he looks back on his younger years, Esherick realized even then he had reverence for skilled craftspeople who possessed talents he didn’t necessarily have.

Esherick even oversaw the execution of designs he created for ironwork while building his 1926 Studio. The local stonemason Esherick worked with to create the building, Albert Kulp, also happened to be a blacksmith worth his salt. It’s unclear whether Kulp had forged more than the necessary horseshoe before working with Esherick, but oral histories suggest he forged the hinges for the Studio’s loading doors. Esherick apparently stood behind Kulp while he worked the iron, explaining how he wanted them to look! While Esherick was the one instructing this time, he undoubtedly respected and relied on Kulp’s skilled artisanship.

Some metal, like aluminum, was soft enough that Esherick felt comfortable enough working it himself. When Esherick began to work with wood in the 1920s, aluminum was becoming cheaper to mass produce and more affordable for everyday people to purchase before we entered the era of aluminum homes, trailers, infrastructure, and foil after World War II. This newly affordable material was also malleable enough that Esherick could work it with woodworking tools like rasps, files, a bandsaw, and router. An aluminum top was incorporated into Esherick’s original design for the 1929 Flat Top Desk, before it was replaced with the current walnut top in 1962. Might Esherick and John Schmidt have cut this aluminum top themselves? Moreover, Esherick carved a brilliant, twisting aluminum crochet hook in 1944 for Elin Rove, an old friend of his and Letty’s.

Exploring Esherick through a material less commonly associated with his oeuvre highlights many of the complex relationships Esherick had to navigate as an artist. Esherick’s correspondence with the Modern Art Foundry shows us how the artist sought to advocate for his clients, many of whom he considered to be close friends. This correspondence also highlights how Esherick navigated complex situations between old clients, new clients, and the businesses this artist had to work with. However, exploring Eshericks’ relationship and work with metal shows us his reverence for skilled craftspeople working in a variety of materials, and helps to highlight his network of collaborators.

Want to learn more about the lost wax casting process? Check out this animation by Hyperallergic: https://hyperallergic.com/286780/an-animated-guide-to-the-bronze-age-technique-of-lost-wax-casting/

Post written by Public Programs & Collections Manager Ethan Snyder

September 2023