Hedgerow Theatre, Image courtesy of Wikicommons and Smallbones.

This month’s article was originally published in the Wharton Esherick Museum Quarterly from Winter 1986.

It was only natural that Wharton Esherick would be attracted to Rose Valley and the Hedgerow Theatre. Between 1901 and 1916 Rose Valley had been converted from a deserted textile mill town into a community of artists and craftsman. In an ambitious experiment, architect William Price and his associates, following the precepts of John Ruskin and William Morris, sought to restore quality in design and workmanship in crafts and architecture, in an effort to counter the monotony and ugliness of design brought about by the mid-nineteenth century industrialization. Their Rose Valley Association, a business venture supported by several prominent Philadelphians including Edward Bok and the Fels brothers, was created “to encourage the manufacture of such articles involving artistic handicraft as are used in the finishing, decorating and furnishing of houses.”

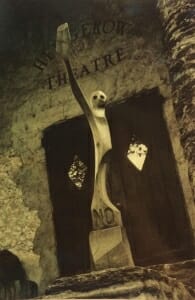

“NO!” (1934, pearwood) was Wharton Esherick’s version of a ‘Do Not Enter’ sign for the balcony of the Hedgerow Theatre.

The largest of the mills became the Guild Hall, a meeting place for a community of artists, another mill became a furniture shop. A pottery studio and a metalworking shop were added to the complex, and the old workers’ houses were rebuilt as residences for the craftsmen. New houses were designed by William Price in his “Rose Valley Style,” distinguished by red tile roofs, fieldstone and earth-tone stucco and incorporating Mercer tiles and the products of the Rose Valley craftsmen. Although the venture was influential in developing a respect for crafts in the Philadelphia area it was not a financial success.

In the summer of 1923, Jasper Deeter, a young actor, walked into this community en route from Swarthmore, where he was performing with a Chautauqua circuit theatre group, to visit his sister Dr. Ruth Deeter in Media. He had recently left the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village out of concern that the well-known theatre would lose its quality in a proposed move to a larger house in the Broadway area. For weeks he had been looking for a small theatre in which he and fellow actors from Provincetown could develop a new permanent company, “Where theatre artists might work together to produce fine plays, where their freedom to create would be restricted only by the limitations of their skill and imaginations.” The Guild Hall in Rose Valley was just what they wanted. Deeter acquired the mill from the failing Association and soon their new theatre company was performing its first production of Shaw’s “Candida.”

The large woodblock for Esherick’s “The Heart of Youth” poster is signed (carved in the bottom corner) “WHE 1924. To J.D. and his Troupe, Rose Valley.”

Ruth Deeter and Letty Esherick had been friends for years, sharing a common interest in “organic diet,” so news of the new theatre group reached the Eshericks quickly. The two men hit it off – Deeter’s acting theories and methods appealed to Esherick as Esherick’s sculptural theories and forms appealed to Deeter. Deeter had no difficulty persuading Esherick to design the set, costumes, and lighting for their 1924 production of Hagedorn’s “The Heart of Youth”. Esherick also carved a large woodblock (now in the Museum) from which he had printed the promotional poster.

Eventually, the entire Esherick family became involved in Hedgerow. Letty Esherick’s brother Ferd Nofer joined the Company immediately after graduating from Swarthmore in 1924. The three Esherick children, Mary, Ruth and Peter appeared together in the children’s roles in the 1933 production of “Thunder on the Left.” Mary had joined the theatre company in 1932 after several years of children’s roles during summer vacations. Ruth followed her in 1939 and remained until 1956, and for several years Letty was head of the sound department while Ruth managed the lighting.

Esherick applied his hand to set design again in 1930 for Ibsen’s “When We Dead Awake” creating two sets of abstract forms, one prismatic, the other curvilinear, to which the action and dialogue gave meaning. [Miriam Phillips, Wharton’s companion in the latter half of his life, acted in the production as well.] The wood original of his 1932 aluminum sculpture Speed was made as a stage prop for Ervine’s “The Ship.” He made various other props including a small table that appeared in many of the Shaw plays, and a set of 5 or 6 nesting chairs with bolt-on backs for the traveling production of Moliere’s “The Physician in Spite of Himself.” Perhaps his most interesting costume was the Lion for Shaw’s “Androcles and the Lion.” The lionskin colored body had a mane of orange and white with touches of blue and red and was fitted with a papier-mache head with a soulful expression of both pain and pleasure. The mouth opened and closed with that of its occupant, usually his daughter Mary.

“Hedgerow Stairs,” wood model, 1936. A major fire at Hedgerow destroyed the actual stairs in 1985. A second Esherick staircase is still in use in the lobby.

The original box office was under the stair to a small balcony, which was used only by staff. To make room for a larger box office, Esherick produced a new spiral stair. In the late 30’s, when the theatre extended one side of the stage house for set storage and a larger light bridge, they called on Esherick to provide a new stair from the basement dressing rooms to the stage level and on up to the light bridge above. This stair, also a spiral, had a two-foot diameter central column surrounded by a two-foot wide stairway enclosed by a solid railing. It was difficult for actors with swords and impossible for hoop skirts.

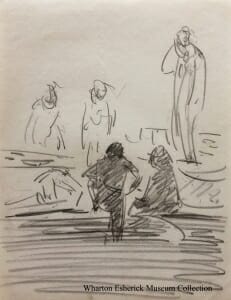

The small balcony provided a perch for Esherick to sketch, and the actors on stage became his models. There he produced more than 4,000 drawings in pencil and pen several of which appear in Drawings by Wharton Esherick, produced by the Wharton Esherick Museum.

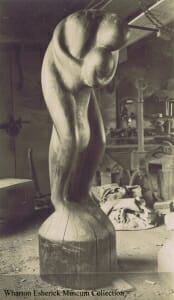

Esherick also carved and printed woodcut posters for the Hedgerow’s production of “Emperor Jones,” “Liliom,” “Hickory Dickory” and for Hedgerow’s appearances in New York during the World War II fuel shortage. He carved two woodcuts of the interior and two of the exterior and one of his sculpture, Darling in the snow with Hedgerow in the background. The theatre and the plays produced there inspired several pieces of sculpture. The Actress (1932) developed from a photograph of his daughter Mary in her dressing room and Oblivion (1934) was inspired by a scene from Hedgerow’s 1933 world premiere of Cozens and Riggs “Son of Perdition.” Camile was inspired by Miriam Phillips’ role as the daffy Camile O’Reilly in Naya’s “Quintin Quintana.”

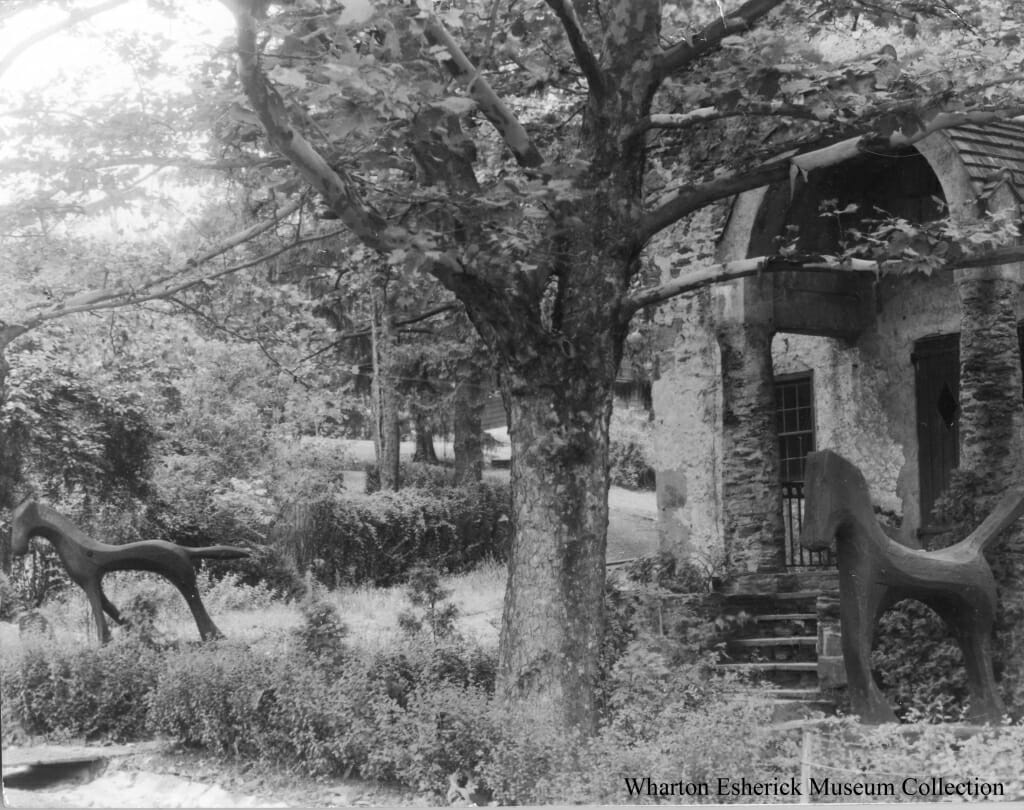

The green room, where the audience gathered before and during intermission, soon became Esherick’s personal gallery where he could exhibit his sculpture in hope of attracting customers. His Finale exhibited there in 1928, was immediately acquired by Mrs. Fischer. Many of the pieces in the Studio were first exhibited there. The larger pieces such as Darling and the two Hedgerow Horses Cheeter and Jeeter stood outside.

The horses were there for many years and to protect them from the weather Esherick would send paint to Ruth for application – sometimes plum, blue or yellow, but never an ordinary horse color. When Cheeter finally moved back to the Studio the alumni of Rose Valley School, who had played on the horses as youngsters, had a bronze casting made and installed in the school grounds for future generations of children to ride.

Esherick also tried acting, appearing in several plays under the pseudonym “John Henry.” His woodcut The Sacristy includes his self-portrait as the milkman in Nichols, “Hickory Dickory.”

“Cheeter” and “Jeeter” outside the Hedgerow Theatre.