The Diamond Rock Schoolhouse is a treasured Chester County landmark, enjoyed by local area residents as a touchstone to the past and to the families that once lived in this region. This modest little building tells the story not only of the people that built the schoolhouse and their children, it also tells the story of those that fought to preserve it generations later, and for a brief while, it tells a piece of Wharton Esherick’s story as well.

After decades of dedicated stewardship by volunteers operating as the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse Preservation Association, the Wharton Esherick Museum is excited to assume responsibility for this unique landmark. The schoolhouse has continued to survive by the care of its neighbors, and now the Museum will take its turn ensuring the preservation and care of this charming site.

Of course, our tie to the schoolhouse is more than just being neighborly – the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse tells a unique part of Esherick’s story as an early painting studio. In this month’s blog post, we hope to shed some light on the history of the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse and its rich connection to Esherick’s creative path.

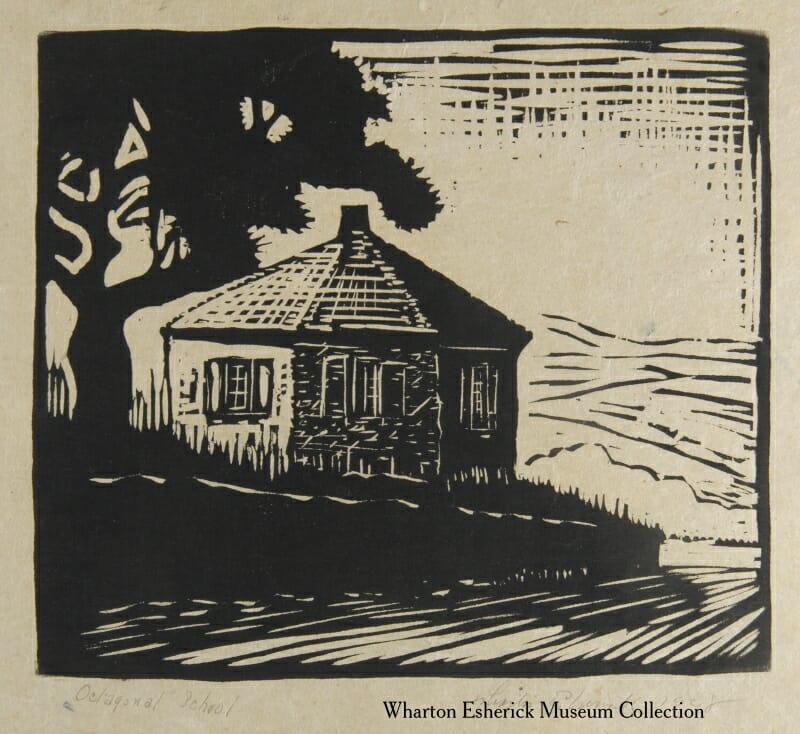

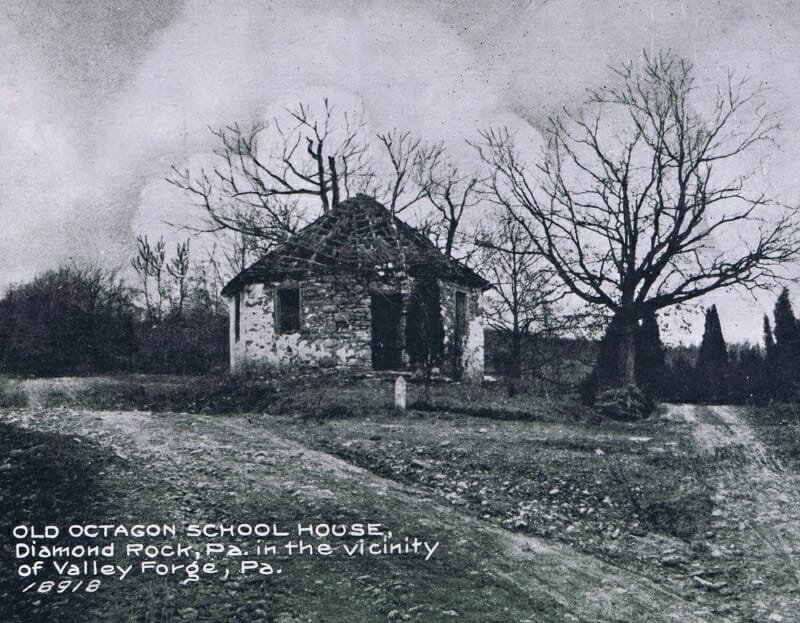

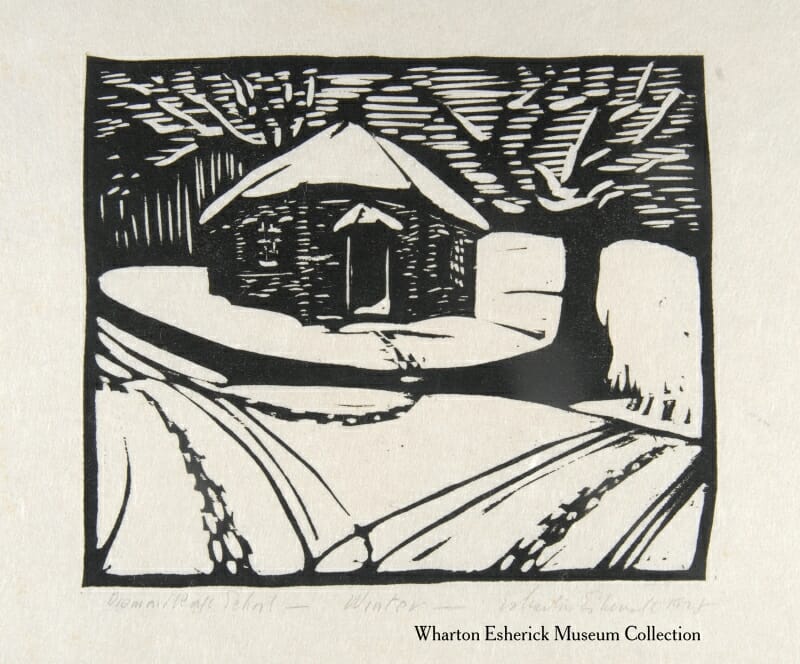

You may have spotted the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse on your last visit to Esherick’s Studio; it stands at the intersection of Diamond Rock Road and Yellow Springs Road, flanked closely by the two roadways and with great, old oak trees at its back. What catches most people’s attention is its form – the schoolhouse is octagonal. The local families who banded together to build the school in 1818 were accustomed to this architectural approach, believing it the most efficient and functional for their needs. In his ‘Diamond Rock Octagonal School’ booklet, Raymond A. Elliott recalls a statement in an architectural journal from 1853: “The nearer in form we can approach the circular the better… The octagonal form serves better than the square and is preferable in every way.”

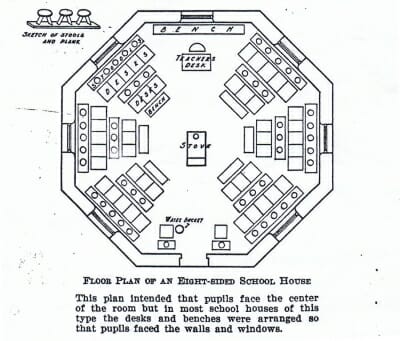

Diagram showing a similar seating arrangement for students. From the Pennsylvania Department of Public Instruction, 100 Years of Free Public Schools.

At the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse, the children were grouped by subject or lesson to each section of the octagon and seated on benches facing the wall. With one wall for the door, and one wall across from it for the teacher, that left room for six distinct groups of students. As the teacher addressed a certain section, that group would all turn to the center to face the teacher. It is said girls were seated at the ends of the bench so they could turn without lifting their knees and skirts. The building had no electricity, of course, but with a window in each section of wall, light poured in from all directions. A singular, small wood-burning stove kept them warm from the center of the room.

This efficient octagonal design could accommodate 60 to 65 students – though it’s likely attendance fluctuated throughout the year. The founding families of the schoolhouse were “folks of but moderate means” as Raymond A. Elliott puts it, and could have pulled children away from school for periods of time, not out of apathy towards their education, but for the seasonal duties that farm work and early 19th-century life required. Indeed these early families made a strong commitment to the betterment that education could bring their children. Some pupils of the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse went on to be teachers, doctors, and ministers, even a congressman had his start here. The 32 families who funded the school to varying degrees can be seen on a copy of the original agreement which hangs in the schoolhouse today, along with other artifacts. While these founders underwrote the schoolhouse, it was indeed open to all, the first ‘free’ or public school in the area, unassociated with any specific church, religion or other organization.

Wharton Esherick’s part to play comes quite a bit later. When Wharton and his wife Letty moved to this area, purchasing the farmhouse they called Sunekrest just up the hill, the school was in considerable disrepair. After providing nearly 50 years of service the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse closed in 1864 and the students were divided between the Walker and Salem Village Schools. The building remained abandoned for decades until local neighbors took up the call to restore the structure. Emma W. Wersler, whose mother and older sister attended the school as children, led the effort along with other former pupils and neighbors beginning in 1909. They called themselves the Diamond Rock Old Scholars’ Association. In the years to come, this organization would become the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse Preservation Association.

Wharton and Letty moved into the farmhouse in 1913. At that time Wharton was still trying to make his way as a painter, and had set up the southern bedroom of their farmhouse as his studio. With the birth of his daughter Mary in 1916 however, he relocated to the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse, renting it from Miss Wersler. He helped with the renovations, adding a new door, new shutters with diamond shapes carved into them (perfect for a school on Diamond Rock Hill!), and poured the concrete floor in a radial “sun” pattern. It is also believed Wharton created the ironwork for the shutters to provide some security for the newly restored building.

Wharton remembered how “Emma Wersler [the owner] was a school teacher and used to always stop in and see me when she came home in the afternoon at the schoolhouse there. She used to stop in and want to see what I was painting and all that sort of thing. Quite a brainy woman. Country woman, but a marvelous teacher.”

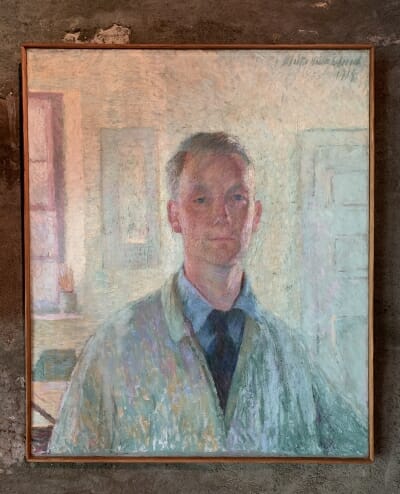

Wharton used the schoolhouse as his painting studio for about four years. He depicted the building many times in his work, particularly in woodcuts and paintings. Wharton was in the schoolhouse when he painted The Octagonal Schoolhouse and his 1919 Self Portrait, which is seen regularly on tours through the Museum today. Just a quarter mile walk from Sunekrest, the schoolhouse was an ideal location for Wharton to remain close to home and family. Bob Bascom, Wharton’s son-in-law, recalls how young Mary would sometimes go down to the schoolhouse with Wharton, charged with carrying a single piece of firewood down for the small schoolhouse stove (a big job for a young child!).

In the winter of 1919, the Eshericks made their life-changing trip to Fairhope, Alabama, where they developed friendships with progressive thinkers of the day and Wharton began his explorations in woodworking. Upon their return from Fairhope, Wharton began converting the farmhouse barn into a painting studio and woodworking shop. In the seminal biography, Wharton Esherick: The Journey of a Creative Mind, Bascom reflects on the distinctive style of Wharton’s paintings completed while in the schoolhouse. “The earlier paintings [before the schoolhouse studio] were made with flat, smooth brushstrokes, while the later ones have great texture, bolder colors, and more asymmetric compositions.”

The Octagonal Schoolhouse, 1918, Oil on canvas, Wharton Esherick. Courtesy of a friend of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

“That’s when I painted the pictures of the 8-cornered school house and the tree out back.” Wharton once retold, “The tree’s still standing there… It’s a nice painting. I think it’s a good painting.”

While it’s often hard to measure the effect or influence on an artist’s mind, it seems fair to wonder about Wharton’s time in his octagonal studio. The cluster of three hexagons that is Wharton’s 1956 Workshop (co-designed with Louis Kahn, and with likely input from Anne Tyng) shares a brilliant efficiency of form with the octagonal schoolhouse. The floorplan of the workshop is even described as simulating a cluster of diamond crystals – as well suited for Diamond Rock Hill as the diamond carved shutters of the schoolhouse below.

All of us at the Wharton Esherick Museum are excited to assume responsibility for this special piece of our community history and look forward to sharing the warm spirit of the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse with future generations. The schoolhouse will be open during our Second Sunday events this summer in July and August. Details can be found at whartonesherickmuseum.org/events.

A huge thank you to Susanna Baum, President of the Diamond Rock Schoolhouse Association, and all their volunteers for stewarding and sharing the schoolhouse, its history, and its archives – the principal source of the history captured above! A great article on the history of the Diamond Rock Octagonal Schoolhouse by Susanna Baum can be found in the December 2013 issue of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly (Vol. 50 N. 4) published by the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society. https://www.tehistory.org/index.html

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

June 2019