The Trylon and Perisphere at the center of the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair.

Image source: New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York World’s Fair 1939-1940 Records.

Few events leave such a legacy of wonder and spectacle on the national psyche as a World’s Fair. A beacon of hope and potential, 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair undoubtedly left its mark on America and we are excited to highlight Wharton’s contribution to this iconic exposition in this month’s post. To say the fair was expansive would be an understatement. Pavilions sprawled across Flushing Meadows Corona Park covering over 1,200 acres, effectively erecting a temporary city dedicated to the future. Nestled in between the Great Depression and the start of World War II, the fair was themed “The World of Tomorrow” and trumpeted the promise and potential of American ingenuity.

A map of the fair. “America at Home” can be seen next to the information booth (owl icon) circled here in red.

The fair included themed zones and attractions too numerous to list here, including everything from international exhibits at the ‘Lagoon of Nations’ to American industry giants like General Motors and RCA. Over 44 million visitors would attend, marveling at the Trylon and Perisphere (the great spire and orb at the fair center) and all the wonders of technology that surrounded them.

However, it soon became apparent that for all the electricity and aerodynamic cars the fair offered, it neglected to represent the future of domestic spaces. What would our daily lives look like? The “America at Home” pavilion, added to the 1940 season would correct that – and that’s where Wharton comes in!

“A Pennsylvania Hill House” included architecture by George Howe and furnishings by Wharton Esherick. Photo by Richard Garrison.

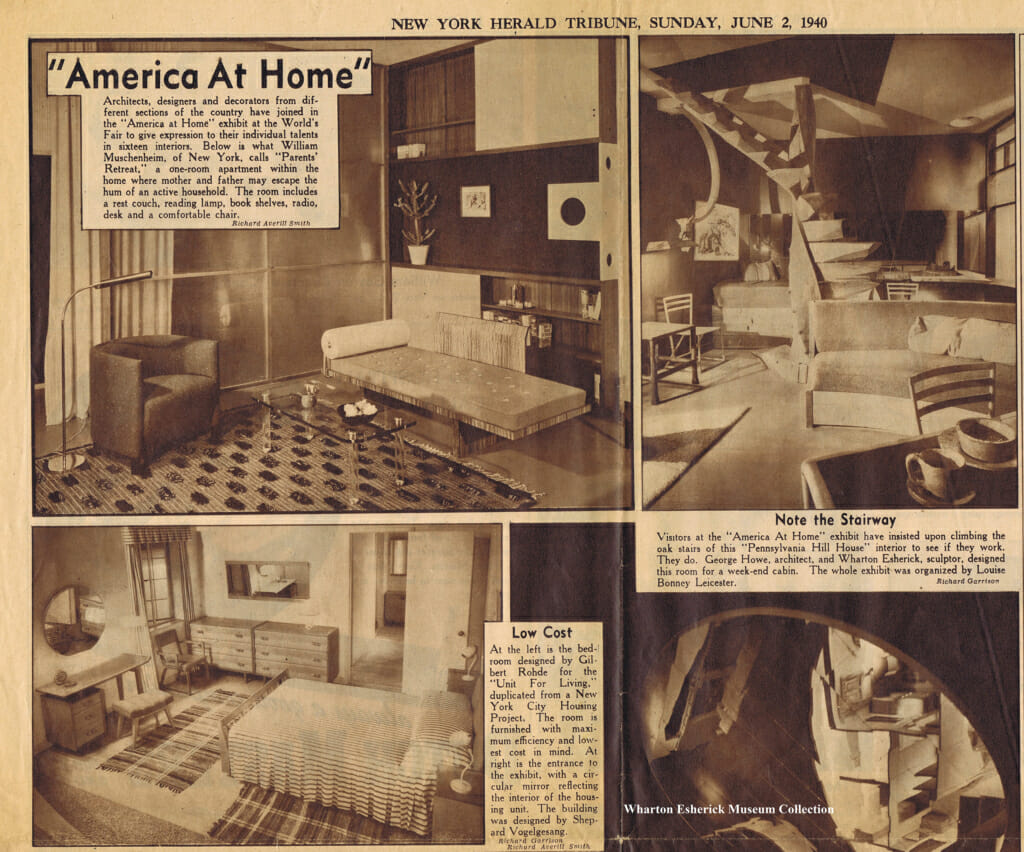

A total of 16 architects and designers were commissioned for this exhibit, each producing a distinct room. One such architect was George Howe, who took the opportunity to collaborate with Wharton. (Perhaps Howe’s most well-known building is the PSFS – Philadelphia Saving Fund Society, the first International style skyscraper in the U.S.) For the fair, Howe designed the surrounding structure, while Wharton created a room display both modernist and rugged, which they called “A Pennsylvania Hill House.”

The display included some particularly iconic pieces, many of which you see on our tour here at the museum – the oak spiral stairs, the Curtis Bok sofa (now in Wharton’s bedroom) and the cherry walls that now surround the dining room, to name just a few. One of Wharton’s newest designs on display at the fair was a five-sided hickory table with black phenol top and a set of chairs derived from his earlier hammer handle designs. These marked a new direction in Wharton’s work, shifting from expressionist lines to lighter, curving forms. As a whole, Wharton’s arrangement was strikingly theatrical, especially when compared to the neighboring rooms. The images that remain reveal a layered, textural space heightened by dramatic light and shadow, and a sense for the warmth and emotional richness possible in design.

Wharton also took the opportunity to include other artist’s work (June Groff and Hannah Fischer are among the names that may be familiar to Esherick fans) and books on consignment from the Centaur Book Shop. A price list Wharton submitted to the fair provides us with a thorough inventory of the room – notably, Sock, the wooden dog footstool which Wharton made for his daughter Ruth on her eleventh birthday, was “Not for Sale.”

The World’s Fair was the first exhibition of Wharton’s work to reach a national and international audience, and seems to have been well received (although the advent of WWII turned America’s focus on things other than art buying). In a letter to Wharton from the America at Home Publicity Director, Lousie V. Sloane, she remarked that, “The ‘Pennsylvania Hill House’ is a very popular room with visitors… and the stairway continues to bring forth exclamations, questions and comments from those who go through the building.” (Sounds pretty familiar to those of us introducing the spiral stairs to visitors today!) Elizabeth Rae Boykin, writing for the Philidelphia Bulliten in 1940, noted how the room recalled Pennsylvania’s “pioneer tradition that translates well into a modern idiom.” It certainly seems to have stood apart in its simultaneous representation of a rugged past and a modernist future, asserting the enduring relevance of the handmade.

Howe and Esherick featured alongside contemporaries from “America At Home” in the New York Herald Tribune.

Check out these sites for more information about the 1939-1940 World’s Fair:

http://www.1939nyworldsfair.com/index.htm

http://exhibitions.nypl.org/treasures/items/show/162

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.