Bold and playful, this textile design by June Groff was acquired by Jack Lenor Larsen, Inc. as “Spice Garden.”

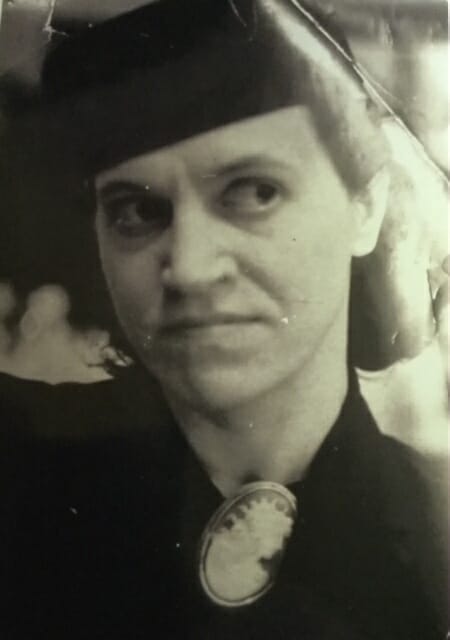

Wharton Esherick’s work is often described as having integrity, and an honesty that cuts through any art jargon one might try to apply. As his nephew, the architect Joseph Esherick put it, “In his work [Esherick] spoke as an individual, but not in a private language, with the result that he and his work speak to everyone.” One could make a similar claim, and some have, about the work of artist and textile designer June Groff. Her hand-painted and printed fabrics were “done with a dash,” as Barbara Barnes put it in a 1949 Philadelphia Bulletin, ”and with complete absence of artiness or affectation.” Like Esherick, Groff seamlessly merged the skills of academic training with the world of everyday objects. The result? Work that sings unselfconsciously with the pure, joyous energy of creating.

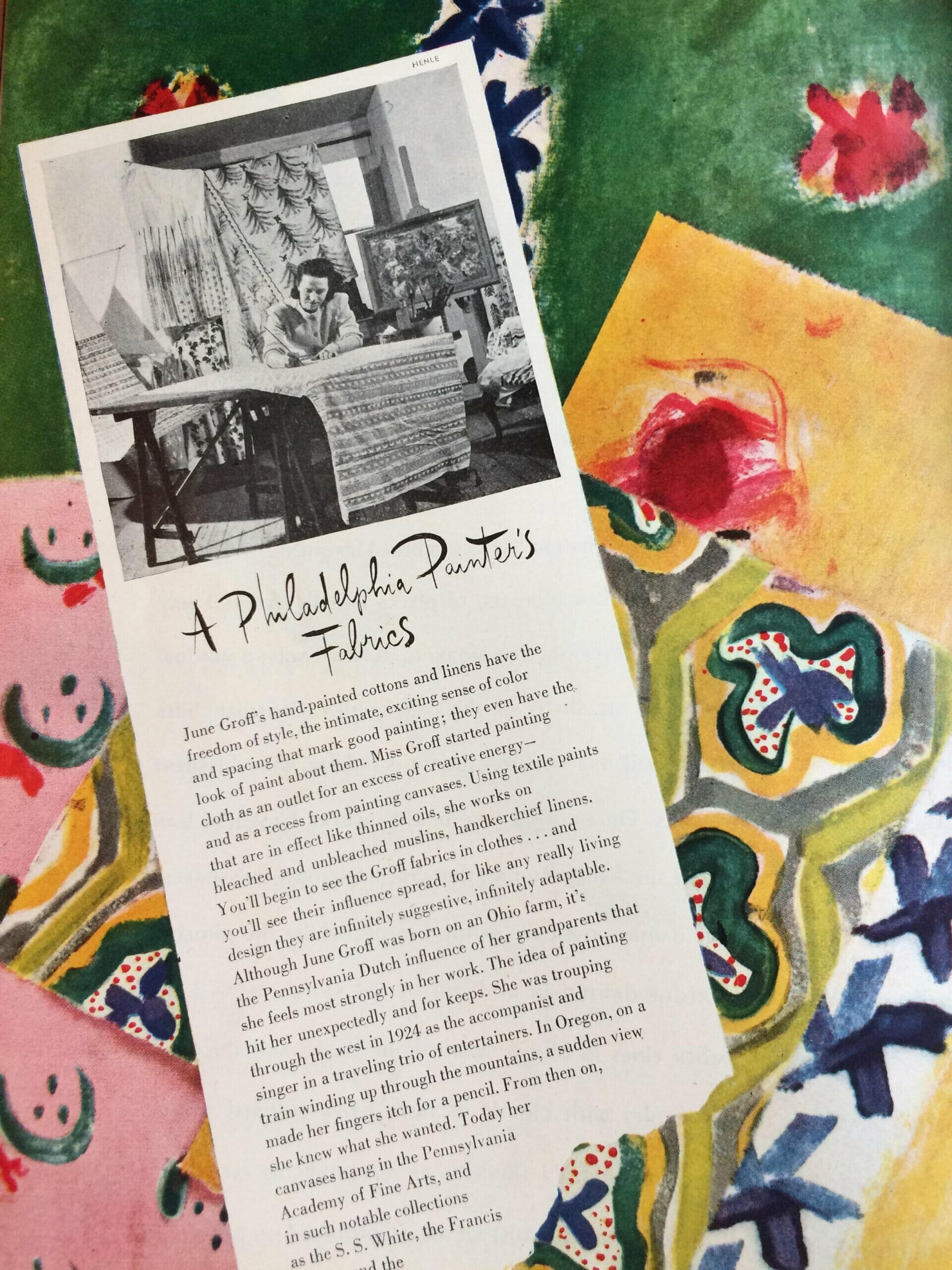

Born in Ohio, June Groff (1903-1974) was a farm girl of Pennsylvania Dutch heritage who later found great inspiration in returning to her childhood memories of barnyard animals, red schoolhouses and country scenes in her work. She would later recall admiring her sister’s watercolors as a child, but would not realize herself as an artist until much later. Her life took a more meandering path and her initial studies were in music and dramatics. For several years she traveled the west as an accompanist and singer, one in a trio of entertainers, when in 1924 she was struck by the inspiration to paint. By Groff’s own recollection, “It was an Oregon mountainside, with fuzzy dark spruces poking their heads up through blankets of snow that made me want to paint. Studying art became my dream from then on, but it was several years before I could afford the art studies.” When she did finally begin her training she worked prolifically and aptly in many mediums, including oil paintings, watercolors, embroidered “needle paintings,” stained glass and hand-painted and hand-printed fabrics (and poetry too!)

Groff’s first art courses were at New York University (1928-1929), followed by five years at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts including a Cresson Scholarship to study and travel throughout Europe. Upon returning, she spent two years studying at the Barnes Foundation, and within a year had a piece on display in second half the New York World’s Fair in 1940 in (you guessed it Esherick fans) the Pennsylvania Hillhouse exhibit. This interior domestic display well-known to Esherick fans was designed in part by architect George Howe and included primarily Esherick furnishings from his celebrated spiral staircase to the world’s fair table and chairs. Sprinkled among the furnishings was Groff’s Bull Over Spain, a decorative yarn panel hung on the wall.

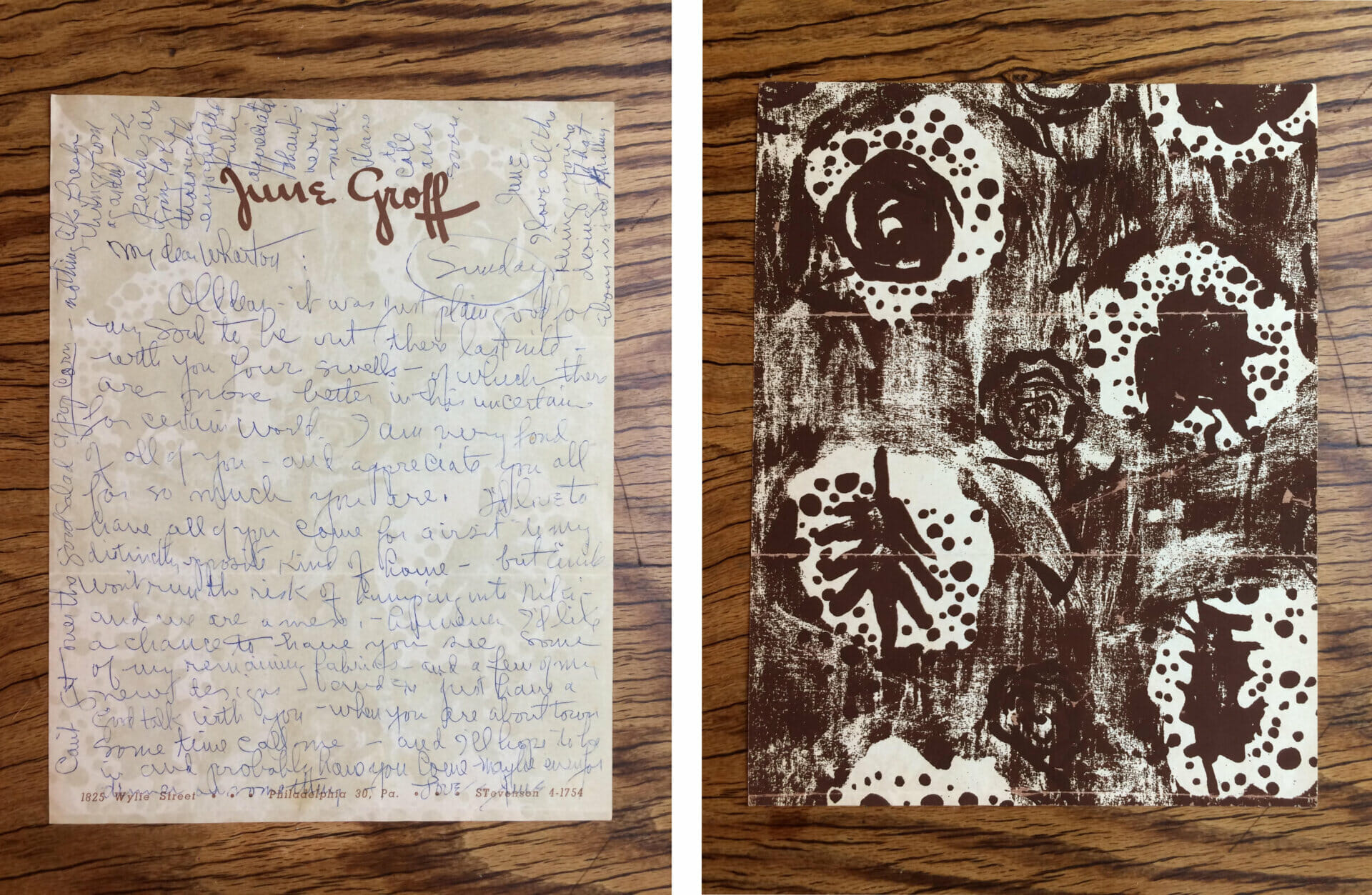

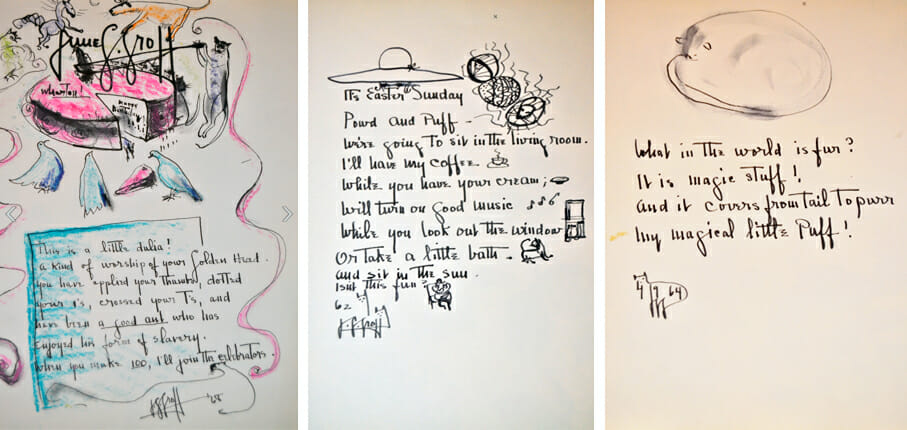

It’s hard to know when June Groff and Wharton Esherick first met. They would come to show together many times over the years, but surely this exhibit would have put them in touch. As two artist living and working around Philadelphia, their lives overlapped in other ways, too. One of Groff’s good friends, Bess Hurwitz and her husband Nathan, were also Esherick’s friends and collectors (buying his Five-Sided Table from the World’s Fair when no one else would). Groff was a driven and independent spirit; it’s easy to imagine she and Wharton getting on well together. In one letter to Wharton, apparently after a visit to his studio, June begins (in her exuberant handwriting): “My Dear Wharton, Old Dear – it was just plain good for my soul to be out there last nite … I am very fond of you all – and appreciate you all for so much you are,” going on to insist he visit her to see her new designs, and thanking him emphatically for delicious popcorn and peaches from the previous evening.

Esherick owned several fabrics designed by Groff, a few of which are seen regularly by visitors to the Studio. Two pillows made with her fabrics rest on the Bok sofa in his bedroom, one a printed motif of continuous trees, the other a heavier fabric with a basketweave design of loose blue and green brushstrokes. It is likely the colors have worn away considerably on this basketweave design, as decades ago this fabric covered Esherick’s rail sofa across from the fireplace downstairs. After so much use the sofa was reupholstered with the blue cover seen now, but not before saving a section for a pillow.

In the dining room, another pillow of Groff fabric is on display, featuring large, loose and confident oval brushstrokes with hints of turquoise and faint pink. On the wall behind the bench where the pillow sits (a favorite spot of Esherick’s) a June Groff oil painting entitled Horseplay shows her fauvist color palette which favored vivid over representational hues.

Our Museum collection also includes yardage of Groff’s kept in storage including two variations of a printed design that would eventually be acquired by Jack Lenor Larsen. Larsen later recalled Spice Garden, as it was named, as being one of the first printed fabrics sold by his company and an extremely successful one at that. Drawing inspiration from nature, this design combines her signature bold, energetic brushstrokes with a masterful sense of color and visual balance. The seemingly scattered pattern (depicting flowers, birds, and butterflies) is held together by a lively visual rhythm of complimentary colors – her vibrant personality coming through with each mark. Over the years Spice Garden was produced in a variety of palettes and materials, including pastel hues on velvet, also in our collection.

June Groff textiles were highly sought after in the 1940’s and 50’s. What began as a singular artist’s studio grew to as many as 30 employees working to produce around 1,000 yards a day from her Philadelphia factory. She sold fabrics to major fashion designers like Hattie Carnegie and Clare Potter and had work featured in Harper’s Bazaar and Paris Vogue. Her work, both textiles and paintings, were collected by major institutions including the Philadelphia Museum of Art (who has her exuberant “Spice Garden” fabric currently on view in their current Modern Times exhibit), the Barnes Foundation, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts as well as private collectors like Emile Gauguin, Francis Biddle, and Vera and Samuel White.

Yet somehow, June Groff managed to fall into obscurity in the later years of her life. She passed away in 1974, and despite the acclaim, she reached in her own lifetime, had come to be somewhat of a recluse in her Philadelphia home, shared with 10 cats and 90 pigeons. Her name seems to be bubbling to the surface again in more recent years, with textiles going on display in Philly restaurants several years ago, or her recent inclusion in the PMA’s Modern Times exhibition, and we can only hope for more. It’s a curious thing, who is remembered and who is forgotten from the history books. June Groff’s role in the Philadelphia art world and beyond should not be forgotten – her quick gestures on fabric, too joyful and genuine to be pretentious, are just one aspect of her work, leaving paintings, embroidery, stained glass and more to be rediscovered. Time and art keep marching forward and we should certainly bring June Groff, her work, and her instantiable energy to create along with us!

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.