Installation view of Esherick’s 1958-1959 retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts. Featured in the image are Darling (1940); white oak; 84″ x 60″, and Spiral Staircase (1930); red oak, 124″ (height). Image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts.

The recent passing of celebrated craft curator and museum director Paul J. Smith got us thinking about the important role of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in sharing and celebrating Wharton Esherick’s work. Smith was an artist himself, drawn to woodworking in particular, though his curatorial interests ranged across all craft materials — even cookie dough. He began working with the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in 1957, curating traveling educational exhibitions including Design—Wood. The museum was founded just a year earlier by the great craft patron Aileen Osborn Webb as an extension of the American Craftsmen’s Council, now the American Craft Council. In his oral histories at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art and the Bard Graduate Center, Smith recalls the great opportunity Design—Wood provided him to meet Wharton Esherick and other “now-masters.” Smith would go on to become Director of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts from 1963 to 1987.

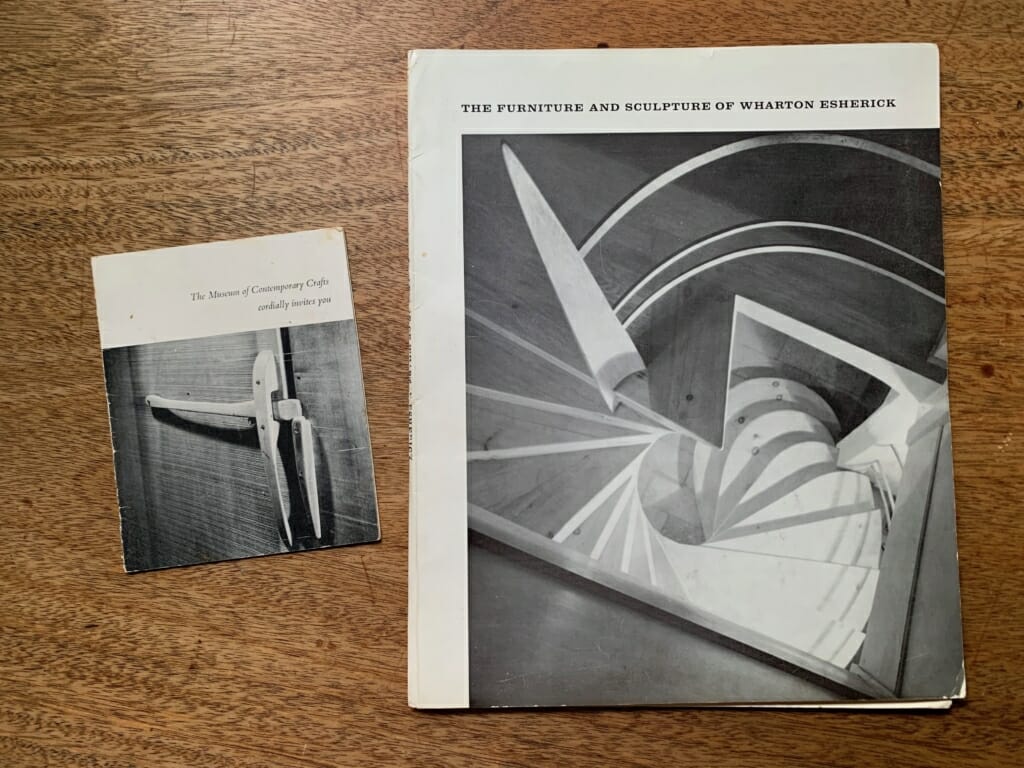

The opening reception invitation and exhibition catalog for Esherick’s 1958-1959 retrospective, The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick, held at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts.

The MCC played a major role in Esherick’s life, most significantly through his 1958 retrospective, The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick. The show ran from December 1958 through February 1959 and included ninety pieces, ranging from early carved works from the mid-1920s through to furnishings made the same year as the opening. It marked the museum’s first major solo retrospective of a living artist, an opportunity that arose from Esherick’s inclusion in the 1957 group exhibition, Furniture by Craftsmen. After a visit to the Studio to select a piece for the show, curators decided Esherick deserved an exhibition that highlighted the long arc of his career, contribution to the world of art and design, and as expressly stated in the exhibition catalog by Assistant Director Robert Laurer, Esherick’s conception of furniture as sculpture.

Installation view of The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick held at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York City from December 12, 1958 through February 15, 1959. Image courtesy of the American Craft Council Library & Archives.

About half of the ninety works in the exhibition were lent by clients and friends. The rest came from Esherick’s own holdings, including large works like his Spiral Staircase, on public display for the second time since its debut at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair. The exhibition also included chairs, benches, tables, stools, and cabinets, and smaller objects like serving trays, spoons, and cutting boards. Though not displayed in a domestic space, it was clear that Esherick expressed his design vision across all forms. Textiles and houseplants accented the installation of the exhibit, helping bridge the gap between the gallery and the domestic.

Installation view of Esherick’s retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, featuring Radio and Phonograph Cabinet and Fireside Stool. Radio and Phonograph Cabinet (ca. 1936-1937); cherry; 23″ x 30″ x 28″. Fireside Stool (1958); hickory with rawhide seat; 13″ x 23″ x 15.5″. Image Courtesy of the American Craft Council Library & Archives.

Installation view featuring Cabinet Desk (1958); curly oak, satinwood, walnut, fir plywood, painted plywood splines; 48″ x 106.7″ x 23.8″; Goslings (1927); boxwood, mahogany base; 13.5″ x 20.3″ x 3.8″; and Bedroom Chair (1932); maple, rawhide; 36″ x 18.1″ x 16.9″. Image courtesy of the American Craft Council Library & Archives.

Esherick’s 1958 Cabinet Desk with built-in lighting was brand new at the time and included in the exhibit along with a walnut and ebony-detailed cabinet and desk unit from 1926, one of his first efforts as a furniture maker. Several sculptures and prints were also part of the show, displaying both large scale pieces including Reverence, Twin Twist, and Adolescence and smaller busts like Portrait of Theodore Dreiser and Head of Mary. A complete list of the works on display can be viewed in the exhibition catalog along with an essay by Robert Laurer and a selection of photographs.

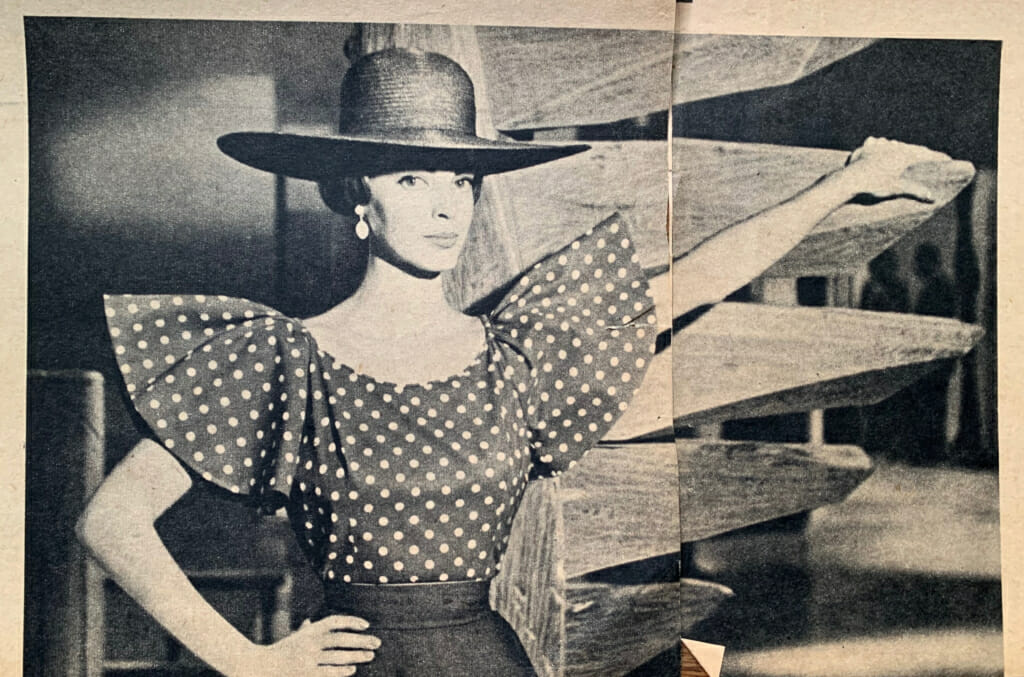

A fashion spread in The New York Times Magazine featured Esherick’s retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts as a backdrop.

The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick received press attention, and our archives include articles from Interiors magazine, The Christian Science Monitor in Boston, and Craft Horizons (the print publication of the American Craft Council), among others. We even came across a fashion feature, ‘Accent on Sleeves,’ in The New York Times Magazine which used the show as a backdrop.

These articles provide insights into the reception of Esherick’s work in his own time, and often include direct quotes – a rarity, since Esherick did not speak frequently about his own art. In her article, “Wharton Esherick” in Craft Horizons (Jan/Feb 1959 pp. 33-37), Gertrude Benson captures a glimpse of Esherick’s process.

“ ‘Look at the wonderful grain in this poplar,’ he said of a mantel he was working on. ‘Did I know it was going to be there? Certainly not, but I am going to make the most of it. Hope I can hold this color. It’s almost like flesh, isn’t it?’ ”

Esherick went on to reveal his need for artistic freedom within his commissions:

“People have to trust me. I work for fun. When I stop enjoying it, I’m through. I don’t want huge jobs that get out of my hands. I want to know everything that happens. I don’t want too many people to worry about. Nor will I work with anyone who keeps trying to pin me down too much. I work best with clients who become my friends.”

We also hear from renowned architect Louis Kahn in Benson’s article, with whom Esherick co-designed his second workshop in 1956. Kahn reflects, “Architects try to learn from nature, searching for a definable, buildable geometry. Wharton works through his feelings. He is as much aware of the captivating beauty of nature in repose as anyone I know.”

In his own letter to Museum of Contemporary Crafts Director Thomas Tibbs after the close of the exhibition, Esherick comments reflect a mixture of self-deprecating humor and gratitude:

“I’m glad that it came at this time in my life, instead of 25 years ago. At that time I would have been so twisted out of shape I wonder if I would have been able to go on in my quiet relaxed way. I’m conceited now; then I would have been impossible.”

Esherick’s 1926 drop-leaf desk and cabinet unit, on view at his 1958-1959 Museum of Contemporary Crafts retrospective, The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick. Image courtesy of the American Craft Council Library & Archives.

Installation images from The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick, the exhibition catalog, Esherick’s letter to Thomas Tibbs, and Gertrude Benson’s article in Craft Horizons, can all be viewed at the American Craft Council Library Digital Collections. Several images noted above were included with permission from the American Craft Council Library & Archives. We’re grateful for their resources, and their continued contribution to the preservation and celebration of America’s craft history. Explore the ACC Library Digital Collections.

Post written by Communications & Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

July 2020