Portrait of Theodore Dreiser, 1933 by Carl Van Vechten. Courtesy the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division. Carl Van Vechten Collection, XV E 11

Few things inspired Esherick like his closest friends, one of which was American author Theodore Dreiser. This month, we re-illuminate this friendship with an article from our Spring 1991 Quarterly Newsletter. At that time, an Esherick and Dreiser exhibit, “A Local Connection”, was on display at the People’s Light and Theater Company.

“The Dreiser-Esherick Camaraderie”

Theodore Dreiser, author of Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy, two truly American novels that broke new ground in literature, is considered one of America’s literary giants.

Dreiser and Wharton Esherick first met at the Hedgerow Theatre in 1924 when Dreiser drove over from New York to see a young woman friend perform there. Arrangements had been made for Dreiser to spend the night at Esherick’s house in Paoli. Esherick, who was seated directly behind Dreiser in the theatre, introduced himself as Dreiser’s host for the night; he was given a once over and then ignored for the rest of the evening as Dreiser concentrated his attentions on the performance and his aspiring friend. However, the two hit it off and became good friends, each respecting and enjoying the other’s genius.

Dreiser, like Ford Maddox Ford and Sherwood Anderson, prominent writers of their times, found a certain combination of solace and intellectual stimulation at the Eshericks.’ Between visits they corresponded, and they each saved the other’s letters.

Within a year after their first meeting, Esherick made a cane in snakewood for Dreiser, carving the handle with a caricature of him. In the summer of 1927 he carved two busts of Dreiser – a sketch in pine, which we have at the Studio, and a finished piece in mahogany, which he gave to Dreiser. It would have been one of the first pieces made in his new studio.

September 1st, ‘27

Dear Dreiser,

Your letter received. We expect to go to Barnegat on the 10th. Will you join us even just for a night?

I want to see the Mount Kisco place very much, I know I could help you with the material end of it, construction I mean. I am conceited enough to feel that you should see my new studio before you make any very large alterations or extensions to your place. It will be an inspiration to you.

Drive down for the night, bring your household – I want to show you the head in wood of T.D. before I exhibit it elsewhere – Someday I will take your offer for a book, at present books are not very close to me.

Many thanks.

Wharton Esherick

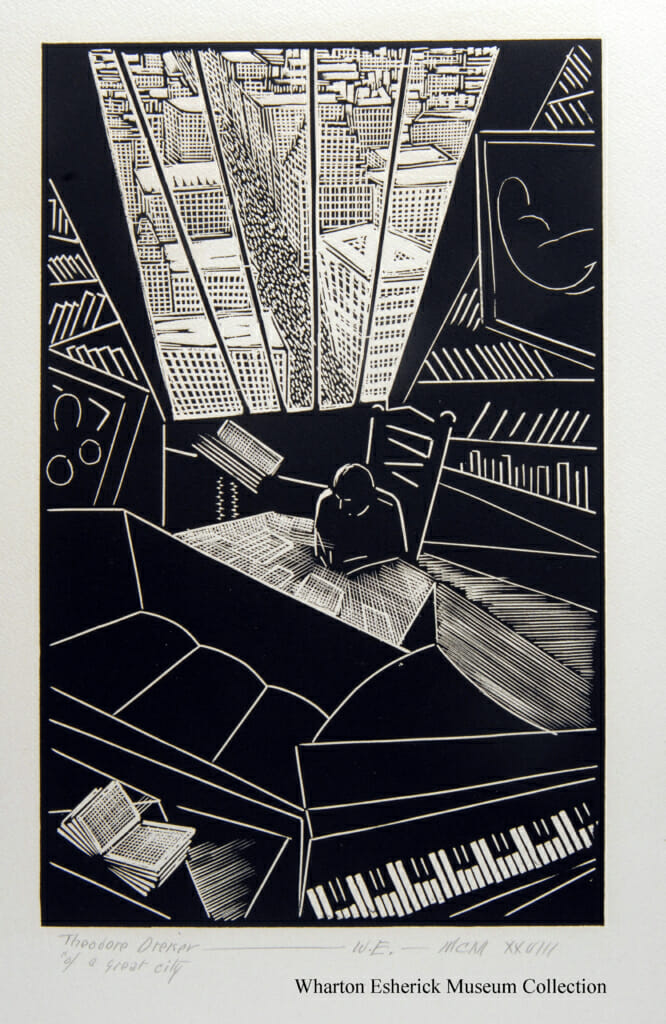

A few months earlier Esherick had carved a woodcut depicting Dreiser at work in his New York studio. On September 9, 1927, he wrote,

… It delights me to hear how you feel about the woodcut “Of a Great City” – I had intended to send a print to a magazine but not until you, the subject, saw it. I am sending it to Vanity Fair.

In the mid-1920s Esherick made a series of trestle tables, each a little more refined and sculptural than the last. In 1928 Dreiser commissioned one with a raised lip around the perimeter in the manner of shipboard tables.

The Eshericks spent the winter of 1929-1930 at Fairhope, Alabama, a “single-tax” community based on the economic philosophies of Henry George and a winter gathering place for artists, writers and other “free-thinkers” of the time. On January 27 Esherick wrote Dreiser,

… This is a full town, full of all kinds of isms, the philosophical kind, you know. On Sunday mornings a group of 30 or 40 meet to discuss open subjects at each other’s house. Breakfast is served and then a chatter. When they met here I opened up with the Bible (Good Samaritan passage). The crowd was surprised as it was the first time the Bible was brought into the meter. Even these intellectuals are scared. I didn’t do it for a joke either. I followed it with Anderson’s mountain girl story in Vanity Fair – a “good Samaritan” act which didn’t work out. Then the crowd tore Anderson apart as only these parlor intellects can do it, missing the point of the tale. After that I brought forth your Forum article, “What I Believe.” It was read by Judge Totten and it was grand to see them scratch and fight like chicks over a worm, not knowing what to do with it after they got it. There was one, a young actress from New York, who cut your head off with one swipe, says you say the obvious, whatever she means … She did apologize after the meeting. A young single-taxer was much impressed and the article brought from him some good honest statements. It is an interesting group if you like groups, but they seem to be trying too hard to find out how to have fun.

Esherick was encouraging Jasper Deeter at Hedgerow Theatre to produce a dramatization of Sister Carrie. On May 8, 1931, he wrote:

I would like you to see Deeter’s production of “Pinwheel” by Faragoh. A strong exciting piece of directing and so simple and economical both materially and actingly. They play it Wed. 13th … Deeter is doing some excellent things and I am anxious to see what he does with your Sister Carrie.

Although “Sister Carrie” never came to fruition, Hedgerow did perform a dramatization of An American Tragedy in 1935.

Esherick suggested that Dreiser try his hand at painting, and Dreiser, in turn, nurtured Esherick’s trial efforts in writing. Esherick wrote Dreiser September 16, 1932:

It’s good of you – encouraging to think my thoughts worth putting down on paper. I recall that time in a little Italian restaurant in lower New York when you, Helen and I sat over the last of a meal, table cleared, and you took the salt shaker and piled the white grain on the white cloth, spread it with your hand like dry sand we play with by the sea. I watched you while we talked, making patterns, designs. I said you should paint or draw pictures if for no reason but to just amuse yourself. You said, “Don’t be a fool, Esherick. I know I can’t do it; I express myself in other ways.” … If I saw a pot of golf in writing I feel I would go into it, even though I often have stated that I would never go after a living – no, after money through art. I would rather push a plow than a pen or brush for money. But – what are our rules and statements for but to be twisted in a cyclone? When does the new magazine come out? Do you need any drawings for it?

In response to a letter from Dreiser requesting an article about the building of the studio for his new magazine, Esherick wrote on October 27, 1932,

Your persistent flattery and praise has forced it out – I’m thrilled to have such a man as you believing in me. I was at the shop alone the other day working on a new stool when suddenly I went to my desk and wrote off the ‘building” article, and the very next day I get a letter from Helen asking me to write an article – What a power you are! Here I am stuck away on a lonely hill – running away from people with my few talents, trying to keep them polished. It almost seems like weakness not to stand up and fight, but yet I see it as useless to buck against the mob. Most of my effort goes into a chunk of wood. Deeter once said to me you should be happy that you are working with oak instead of people. But words, people, or oak have their qualities which must be directed…

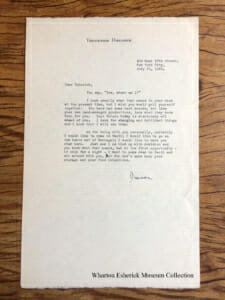

The article was never published and Esherick abandoned hopes of finding any gold at the end of the writing rainbow. Dreiser never risked rejection in painting. But the friendship continued. On February 1, 1941, Dreiser, who by then had moved to Hollywood, wrote:

Fairest Wharton:

I’m to speak in Philadelphia for the Friends of Soviet Russia on March 5 next. My plans and obligations are a little uncertain as yet, – certain peace and civil liberties groups being after me to go here and there. Just the same, with your consent and invitation, I’d like to come out and spend a night or two. I love that place so much and you know how I feel about you…

On May 4, 1942, a year after Sherwood Anderson’s untimely death, Esherick wrote:

Dear Dreiser,

Sherwood’s memoirs are out, and I had great joy reading them. I felt as if I was walking the roads of Virginia listening and in many places I find myself telling. You didn’t know Ripshin, I wish you had, Sherwood would say often “it would be good if Teddy were here now.” I feel that if he could have edited his book he would have left the father part out, it’s been said so often by him. Anyhow it’s a sweet book. I meet many friends in it. Don’t you like how he did you?

I have a friend here, Emil Gauguin the son of Paul Gauguin the painter – he tells me Hollywood is thinking of making a movie of his father, founded as he informs me on Maugham’s Moon & Sixpence which he says is not his father.

David Loew & Levin are to do it – he is objecting & they have offered him $25,000 to assist – but he does not want his father’s life botched with a sex movie. I told him I would write you, maybe with your experience with movies you could put him on the right track to get a good biography of Gauguin. It seems to me it would make a good movie even if they did stick to the truth. What say[?]

I’m still working at woods, sculpture and furniture trying to forget this mess the world is in, hoping they all will not gang up on Russia.

How are you?

Wharton

Emil Gauguin had come to know Esherick through Pricilla Buntin, whom he married, who in the late 1930s had cataloged Esherick’s oeuvre and kept his records for the work on the Curtis Bok House.

Dreiser died on December 28, 1945, at his Hollywood home. He was 75. Esherick was 58.

For more on Dreiser and other authors in Wharton’s library check out our previous post, Wharton Esherick–Reader of Banned Books?, written by Lynne Farrington, Curator of Printed Books at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of the University of Pennsylvania.