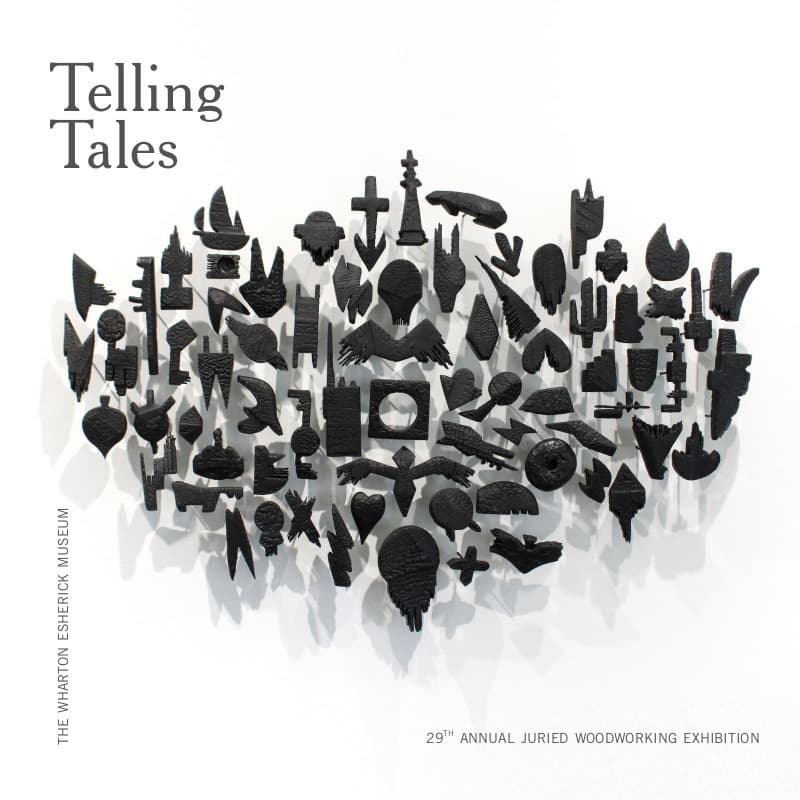

Telling Tales

29th Annual Juried Woodworking Exhibition

June 1, 2023 – August 27, 2023

Stories allow us to make sense of the world, find new perspectives, and explore how we want things to be, even if that is very far away from how they are. We understand ourselves through the stories of others. Everyone has an impactful story to tell.

Telling Tales, the Wharton Esherick Museum’s 29th Annual Juried Woodworking Exhibition, celebrates the importance of storytelling in Esherick’s life and career by featuring twenty-five artists whose work is a testament to the power of a well-told story. Across a wide array of artistic approaches, Telling Tales showcases how skillfully and effectively wood can be used to tell stories drawn from the expanse of human experience and feeling.

This virtual exhibition features the works of all 25 included artists. These works are also available for viewing in a publication which is available as a digital download or in hard copy. The artworks selected for First, Second, and Third place and Honorable Mention will also be on display in the Visitor Center through August 27th. Our Visitor Center is open during our current tour hours (Thurs – Sun 10am – 3pm). Please note, guests wishing to enter the Studio must make advance reservations for a tour. Be sure to visit the Wharton Esherick Museum Facebook page to cast your vote(s) for the Telling Tales Viewer’s Choice prizewinner– voting is open to the public through June 9th!

Many of the works showcased in Telling Tales are available for purchase and the WEM store also features new jewelry and home-goods made by artists featured in the exhibition, including Morgan Hill, Anna Hitchcock, and Colin Pezzano.

2023 Guest Jurors: BA Harrington and Adam John Manley

BA Harrington is a wood artist, Professor of Woodworking, and Director of the Wood Center at Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP). Adam John Manley is a wood artist, Assistant Professor of Furniture Design and Woodworking at San Diego State University, and the co-founder of the contemporary craft zine/journal, CRAFT DESERT.

First Place: Lucia Garzón

Lucia Garzón, Dad’s Cart, 2019. Wooden janitor’s cart, caution sign, broom, video, 42” x 30” x 42”

“Dad’s Cart is a wooden replica of the janitor’s cart that my dad uses to clean buildings at night. When I was a kid, I would go to the office buildings with my dad to help clean. I have fond memories of these times and I wanted to recreate them out of wood, which has a tough and raw materiality that relates to the subjects of my work.

I often show Dad’s Cart alongside a video of my dad cleaning an office bathroom with wooden cleaning supplies that I made, including a wooden spray bottle, plunger, and duster.

My work investigates the intersection between my personal experiences growing up in a multicultural immigrant household and the many different customs, traditions, and stories that my family has passed on to me. Through an interdisciplinary practice including installation, textiles, wood, and video, I address the complexities of trying to honor and navigate the dense histories of my family. Immigration, labor, and personal identity are some central themes present in my work which aims to celebrate my family’s resilience and reveal the many futilities of living and working under a capitalist society.“

Lucia Garzón is an interdisciplinary artist working in a range of media including wood, textiles, print, and video. Lucia graduated from Tyler School of Art in 2018 with a BFA in printmaking. The main themes in Lucia’s work focuses on the intersection between personal identity and the immigrant values and histories passed on through her family. Lucia was awarded the Joseph Roberts Foundation grant in 2019 along with a solo show at Da Vinci Art Alliance. Lucia has been an apprentice at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, attended Acre Residency, and was an artist in residence at University of the Arts ILab. Lucia currently lives and works in Philadelphia.

Second Place: Suzi Fox

Suzi Fox, Gentle Persuaders, 2012. Assorted hammers, 34″ x 2″ x 12″.

“With Gentle Persuaders, I found an assortment of hammers that were about to be discarded. The history of use was visible on each hammer. I kept it very simple and carved them into fingers. The title is a humorous take on the idea that if you cannot get something to conform to your will, hit it hard enough with a hammer.

My work explores connections between the object, tool, and maker. It examines the action of making and my ideas of identity expanded through tools and the objects they create. The maker transfers something of themselves into the work through their labor. These objects are personalized by subverting their function or by adding autobiographical elements. In some pieces, a tool is no longer just an implement of function invisible to the viewer, but the primary focus to be engaged as an object of contemplation.

I am interested in the process as a way to develop ideas. Responding to a material’s inherent characteristics and discovering how to manipulate or emphasize those qualities is my catalyst for art making. At the start of each of my projects, the concept is unformed. The choice of objects and materials I use influences me because they have a history, or a specific memory associated with them. Only when I engage in the cycle of constructing am I able to understand the materials and develop ideas about potential interpretations. This rhythm of physical work and mental comprehension allows my focus to shift to find deeper conceptual relationships in a specific piece or body of work. Ultimately my work explores connections between the process of manipulating material, form, and the potential play of meaning.”

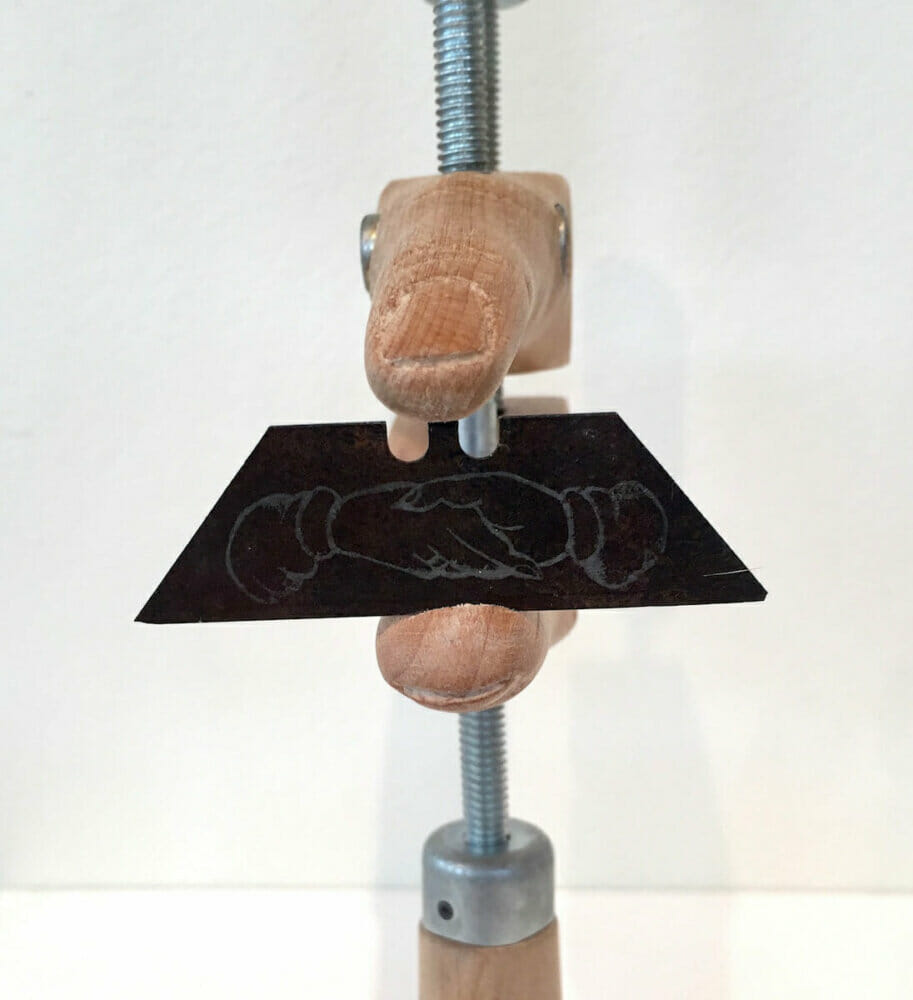

Suzi Fox, How to win friends and influence people, 2016. Jorgensen handscrew clamp, utility blade, 2” x 4” x 10 1/4”.

“How to win friends and influence people gets its title from the Dale Carnegie book. It relates to my personal experiences and observations of how people interact with one another. The Jorgensen clamp, carved into fingers, holds a utility knife blade. On the surface of the utility blade is an etched image of a handshake, a symbol of greeting or agreement. The piece suggests that if someone was to tighten down the clamp, the blade could cut deeper into the wood. The parts are minimal and quick to read, but when connected with the title it introduces an element of humor and irony.”

Suzi Fox is a sculptor based in Virginia; she has exhibited in several national and regional exhibitions. She transforms pre-existing objects into sculptures that playfully allude to navigating interpersonal encounters or that mine her life’s cross-cultural experiences.

Fox received her education from the Rhode Island School of Design with an MFA in Sculpture and from Virginia Commonwealth University with a BFA in Sculpture. She currently works at American University in Washington D.C.

Third Place: John R.G. Roth

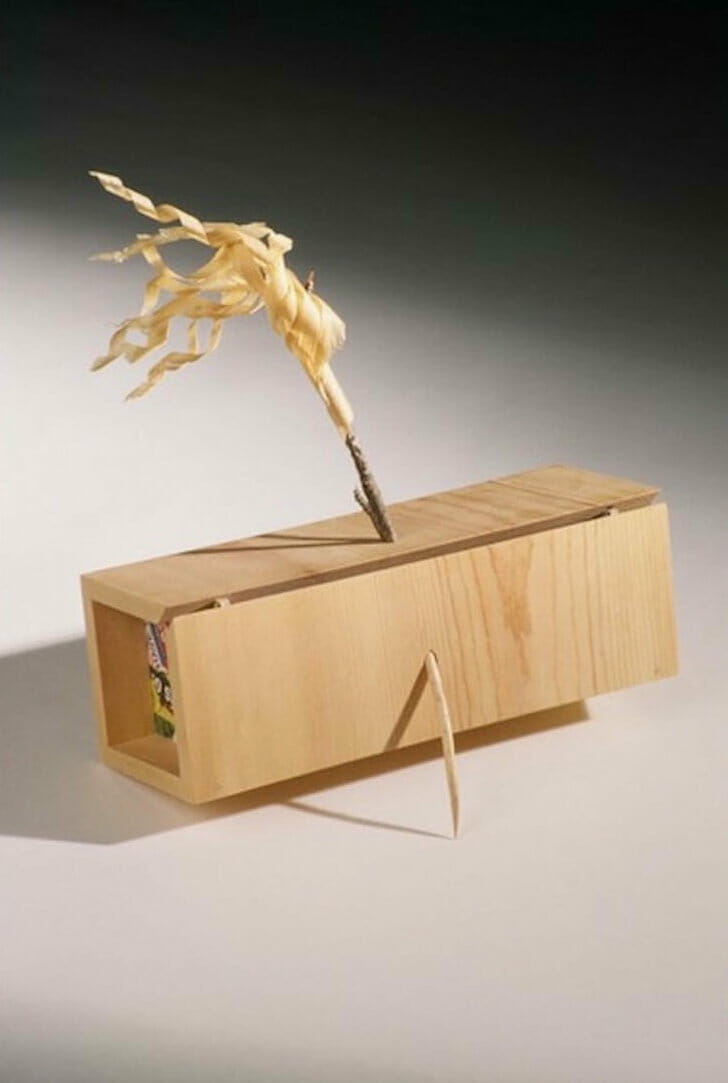

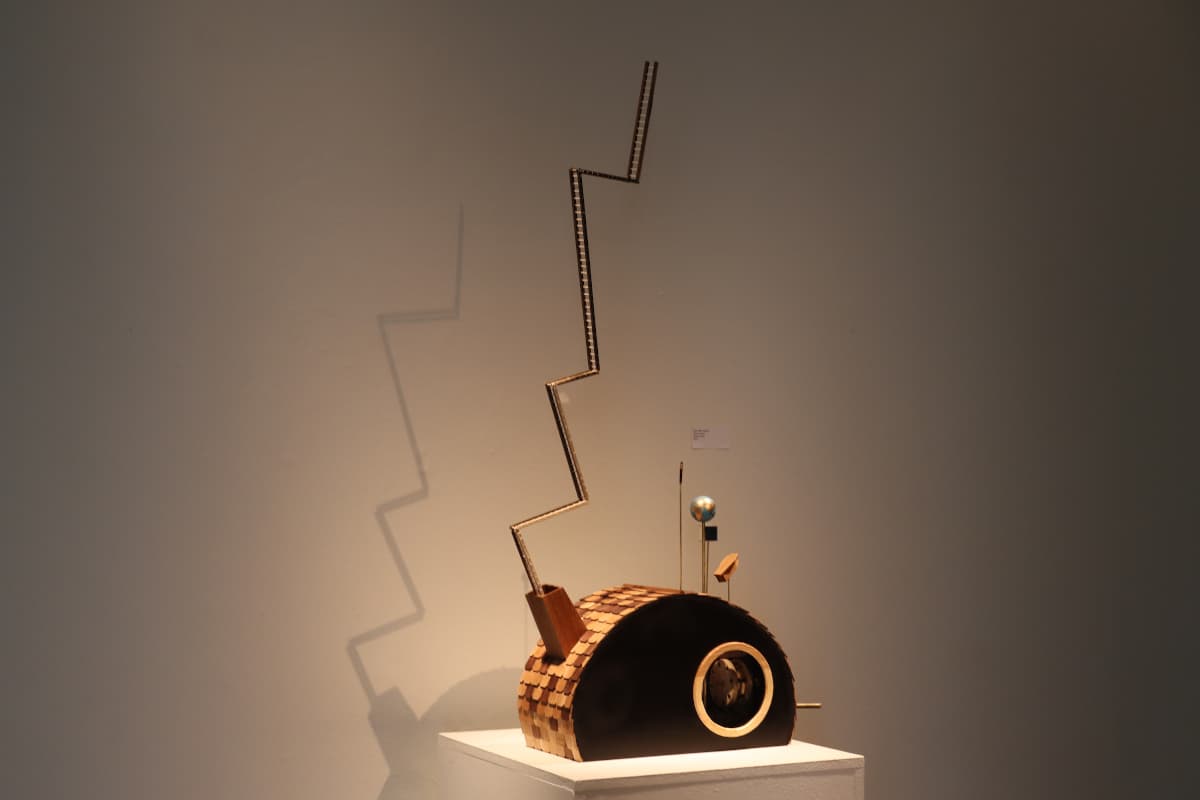

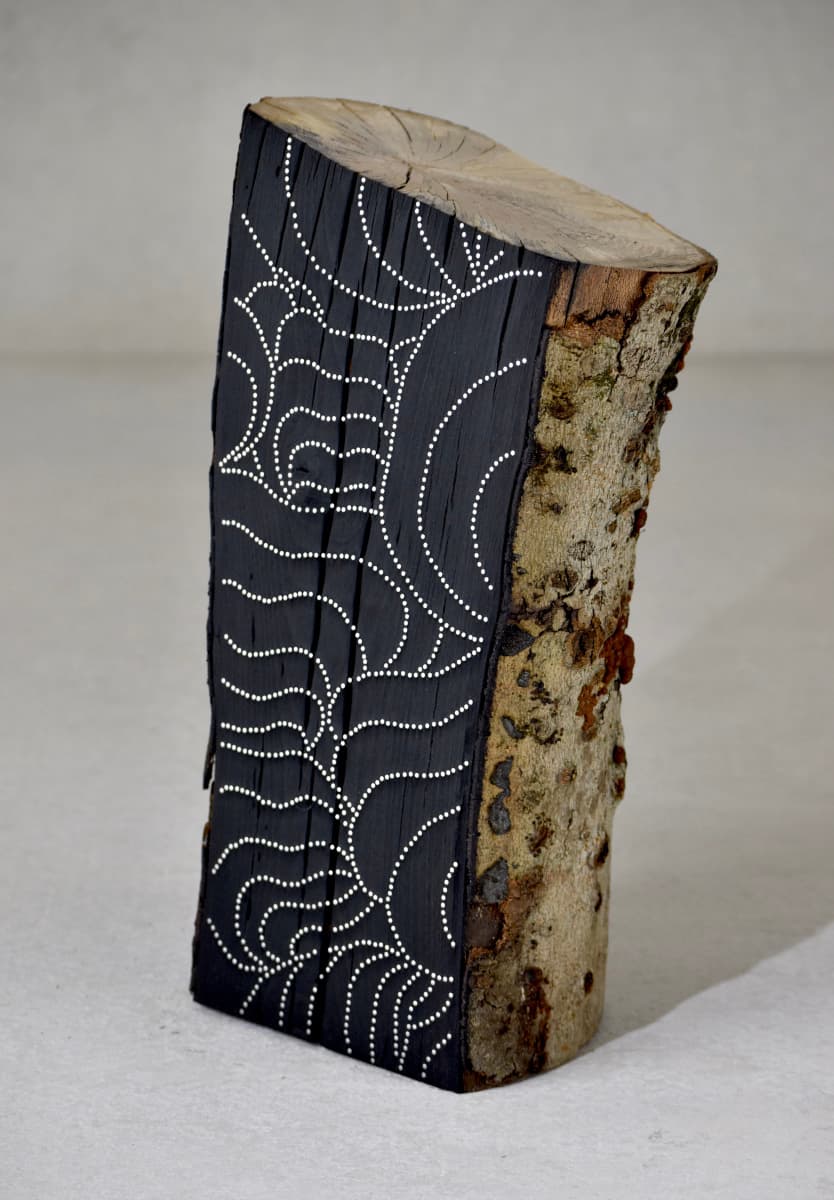

John R.G. Roth, Cenotaph for the Blithely Alacritous, 2020. Cherry, digital image, model scenery, epoxy clay, 20” x 10” x 30”. (top)

John R.G. Roth, Anthropocene Reliquary, 2021. Ebonized ash, digital photo, model scenery, found bone, 21” x 11” x 32”. (bottom)

“These works represent an account of myself as a maker and my very early interest in miniature worlds.

The people of Iceland are making an effort to replace trees that were harvested since the year 1000. This forestry/tree farming was very thought provoking to me during and after my visit. Cenotaph for the Blithely Alacritous is the memorial for the forests harvested in an unsustainable fashion. Anthropocene Reliquary obliquely references the effects of human-kind’s extractive economic model on our life support system. This “reliquary” is both a memento and evidence of past activity.

My most recent works represent a transition that is occurring in my studio practice. Earlier concerns with polymorphic hybrid forms have progressed to include speculative environments to create context. These early forms originated from an interest in anthropomorphism and were partially informed by Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel, Oryx and Crake. Her novel is a vivid depiction of genetic manipulation gone wrong. These new contexts originate from a long-time interest in the interactions of human activity on the landscape and the use of model landscape materials I’ve used for model trains since my middle school years.

In 2016, I spent September at the Gullkistan artist residency in Iceland. That location was a jumping off point for exploring and photographing the various natural features that in many cases serve as the backdrops for my latest diorama works. With this format, I’m working on the nexus of the photograph/model that has emerged from a variant of the film technique of rear screen projection. In these works I hope to invite viewers into a space for contemplation that provokes questions about simulation, display, perception and the human impact on our natural world.”

John R.G. Roth was raised in the Chicago area. He earned a BS Art Education and Industrial Arts Education from Northern Michigan University, and an MFA in Sculpture and Painting from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Before entering university, Roth worked in construction, on dairy farms, in retail management, in a lumber mill, and as a maintenance mechanic in a foundry, furniture factory, and chemical plant. He also taught K-6th grade art in a four-room schoolhouse in rural Michigan. During graduate school, he was employed as a technician in a contract industrial research laboratory where he fabricated laboratory apparatus, models, prototypes and performed destructive testing.

Roth has shown his sculpture in New York, London, Ottawa ON, Chicago, Miami, and Los Angeles. He’s been teaching sculpture for the past 27 years and currently holds the position of Associate Professor and Chair of the Art Department at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.

Honorable Mention: Anna Hitchcock

Anna Hitchcock, These Hands Are Getting Heavy, 2022. Basswood, 16″ x 5″ x 12″. Photography by Mark Juliana.

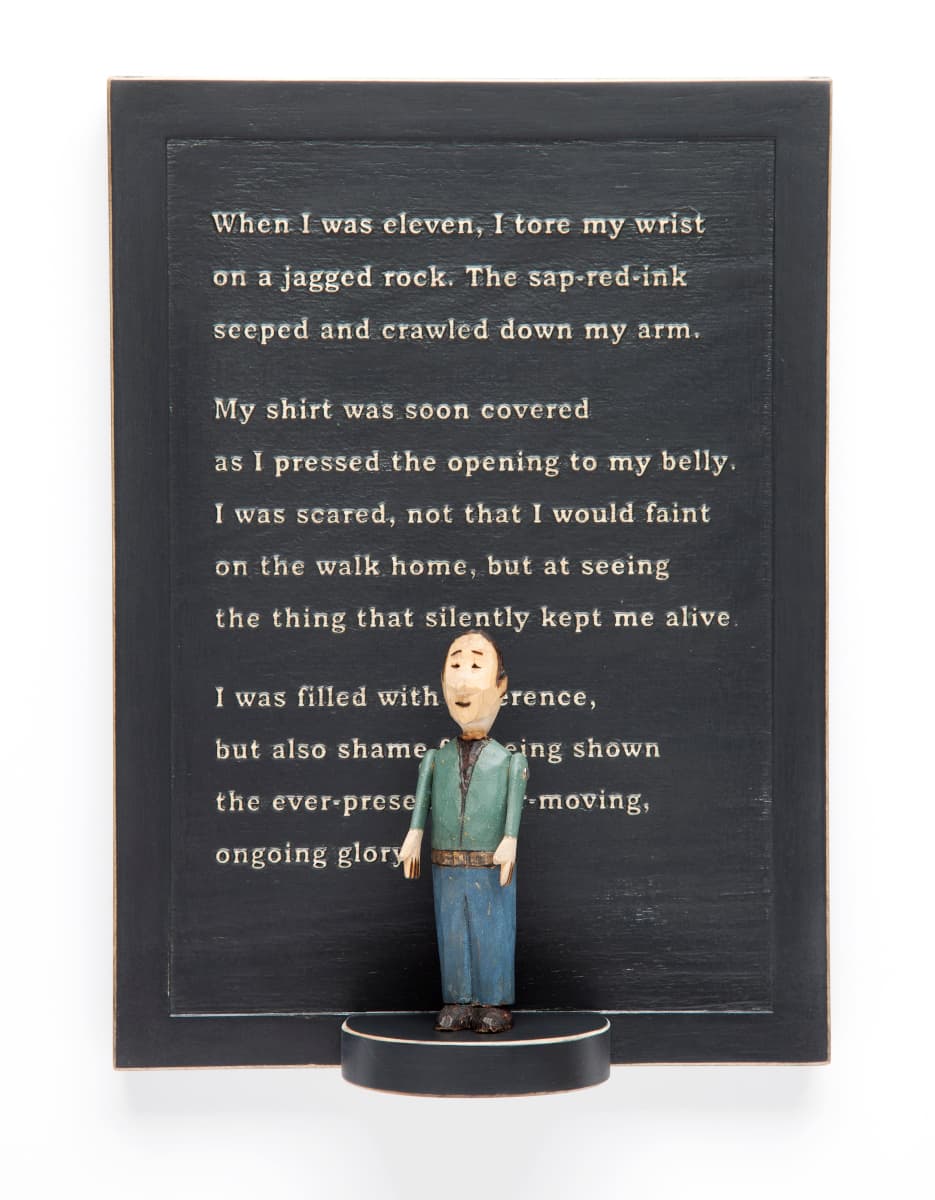

“My work contends with the pressure to fill expectations of vulnerability as a survivor of sexual violence. Through sculptural self-portraiture, I explore the practices of emotional display and concealment as motivated by personal desire and societal coercion.

In the past, I have used graphic figurative imagery to engage viewers’ attention and empathy, opening my story up to emotional voyeurism. This experience has driven me to seek a visual language that will balance my desire for honest vulnerability with protective anonymity.

These Hands Are Getting Heavy consists of a pair of carved hands emerging from the wall. Their position suggests they are carrying something weighty yet unseen, the only proof of their struggle being their strained pose.

The hands’ open posture and raw carving-marks display honest vulnerability and emotion. They are boldly visible with the pain of trauma. Yet, the hands are just a segment of the body they belong to, and their interaction with the wall draws attention to the concealment of the rest of the figure. By denying the audience the spectacle of the entire body, the piece questions the neutrality of its viewers and of the gallery wall.

Although the carved hands show pain and struggle through their texture and position, this sculpture cannot fully convey the story of the trauma within it. Instead, it speaks to the complexities of storytelling in the context of sexual violence. Its focus on concealment highlights the role that deliberate anonymity can play in maintaining resilience and navigating public vulnerability.

Through this work, I hope to expose the complications of relying heavily on stories of individual trauma to catalyze social change. This practice places an expectation of vulnerability on survivors of sexual violence but does little to help carry its weight or defend against emotional voyeurism.“

Anna Hitchcock is an artist and woodworker. Her work focuses on sculptural self-portraiture as a means of engaging with vulnerability. Anna studied art at Macalester College and woodworking at Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Rockport, ME, where she recently returned for an Endowed Fellowship. Her artwork has been exhibited across the country and was included in the 2022 Newport Biennial. She currently lives and works in Rhode Island.

Juried Selections

Learn More

Click on the tabs below to learn more about each artist featured in the 29th Annual Juried Woodworking Exhibition.

Upcoming and Related Events

Spotlight Talk: Telling Tales Artist Lucia Garzón

Spotlight Talk: Telling Tales Artist Suzi Fox

Spotlight Talk: Telling Tales Artist John RG Roth

Telling Tales Catalog

This 70-page, full-color catalog is a comprehensive look at Telling Tales, the Wharton Esherick Museum’s 29th Annual Juried Woodworking Exhibition. This publication captures the innovative works of art, craft, and design by twenty-five artists whose work is a testament to the power of a well-told story. Each artwork in this year’s show is represented through imagery alongside artist statements and biographical information. The catalog also includes a welcome from WEM Executive Director Julie Siglin and an introduction from Emily Zilber, WEM Director of Curatorial Affairs and Strategic Partnerships.