Wharton Esherick outside the Studio, 1961.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, Wharton Esherick created a small compound of sculptural buildings on Valley Forge Mountain. The centerpiece of this hillside campus was Esherick’s studio-residence. The building endures as an artifact of Esherick’s artful work, witnessing the care and imagination that he invested in everything he made. In this way, the Studio presents visitors with a declaration: if work is artful, it can be a home.

Fast-forward to today: the Covid-19 pandemic has upended many of the same work conventions that Esherick dispensed with a century ago—rush hour commutes, office space, and dress pants. But a work-from-home regimen as we know it was not Esherick’s plan. As his architecture shows, even in his idyllic respite from the daily grind, he found value in keeping separation between the spaces of home and the spaces of work.

When Esherick began constructing his Studio in 1926, he intended it as a sculptor’s workspace. By 1941, he was living in the building full-time, having expanded the original stone structure with a towering wood addition. For over forty years, Esherick modified, extended, furnished, sculpted, and painted the Studio into a unique, art-filled building that was, itself, an artwork.

The English novelist and poet, Ford Madox Ford, wrote an early account of the Esherick Studio in his book, The Great Trade Route (1937). Having visited Esherick at the Studio in 1934, Ford described the setting in reverential terms:

A dim studio in which blocks of rare woods, carver’s tools, medieval-looking carving gadgets, looms, printing presses, rise up like ghosts in the twilight while the slow fire dies in the brands…. Such a studio built by the craftsman’s own hands out of chunks of rock and great balks of timber, sinking back into the quiet woods on a quiet crag with, below its long windows, quiet fields parceled out by the string-courses of hedges and running to a quietly rising horizon…such a quiet spot is the best place to think in.

Ford’s writing captures the emotional draw that the Studio exerted—then and now—on visitors. But he left out a major detail regarding the creative work that Esherick was doing at the time. The 1930s were an era of extraordinary growth for Esherick’s career in furniture making. Despite the Great Depression, he connected with wealthy patrons who commissioned adventurous, sculptural furniture designs in wood. The place where Esherick was producing the vast majority of his furniture was not the Studio, but rather, the barn-workshop of his neighbor, cabinetmaker John Schmidt.

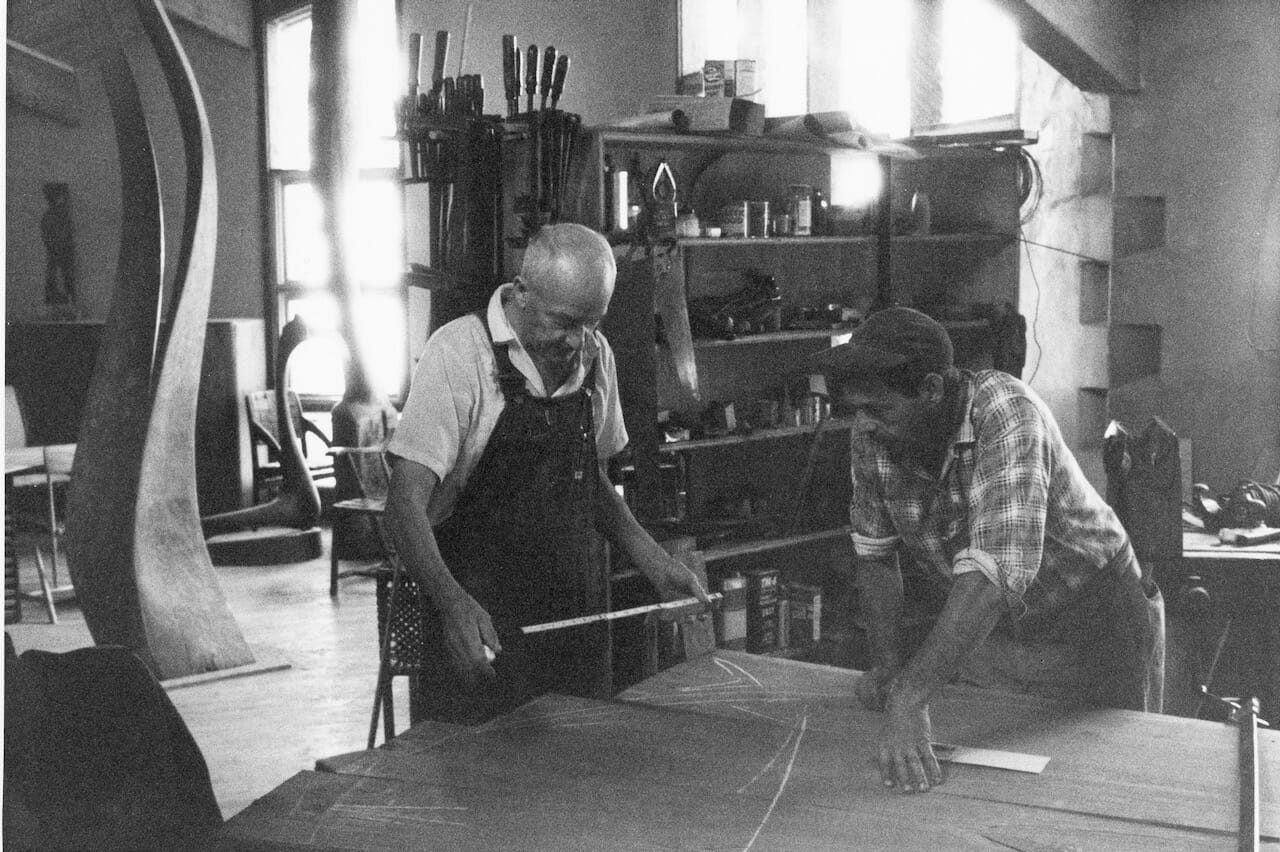

From the 1920s through the 1950s, Schmidt worked for Esherick on a steady basis. His cabinetmaking skill was critical to Esherick’s ability to realize his furniture, as was his shop space. The two men worked closely on Esherick’s projects in Schmidt’s workshop, using his machinery. When, in the 1950s, this work relationship ended, Esherick decided to move his furniture production to his own property. In 1956, he built a new workshop just steps away from the Studio. In this way, he brought his career as a recognized furniture maker in close proximity to his domestic life for the first time.

But this is not to say that Esherick was making furniture at his home. With the 1956 Workshop, he effectively walled off his living quarters from his furniture business. The Workshop, a collaboration between Esherick and the architecture office of Louis I. Kahn, is a concrete block and stucco building. Esherick was hands-on with the siting and design. This fact, taken together with his well-known protectiveness of his privacy, suggests that it was no accident that the walls facing the Studio have no windows.

Horace Hartshaw, a contractor who built the Workshop and later returned to work for Esherick building furniture, spoke about his experience in an interview of the 1980s. Hartshaw, along with Bill McIntyre, was one of two regular employees that Esherick had through the 1960s. Hartshaw’s recollections of his time in the Workshop indicate a space that was set apart from Esherick’s home and marked by the mundane details of employment: salary negotiations; coping with the idiosyncrasies of a co-worker (McIntyre’s smoking and swearing); and routines that included opening the shop at eight-o-clock each morning, cleaning up in preparation for the day’s work, and Esherick’s arrival around 8:30.

Hartshaw also related several reasons that he liked working for Esherick: he was never disgruntled, never talked down to anyone, and kept the Workshop orderly:

So many shops have so much junk around—scraps laying around and chips they never clean up. But Wharton kept his shop very neat and kept his wood stored on shelves and different things in bins. And we vacuumed the floor every Friday. It was a pleasant place to work, because of the windows that let the sunlight in there and gave a view.

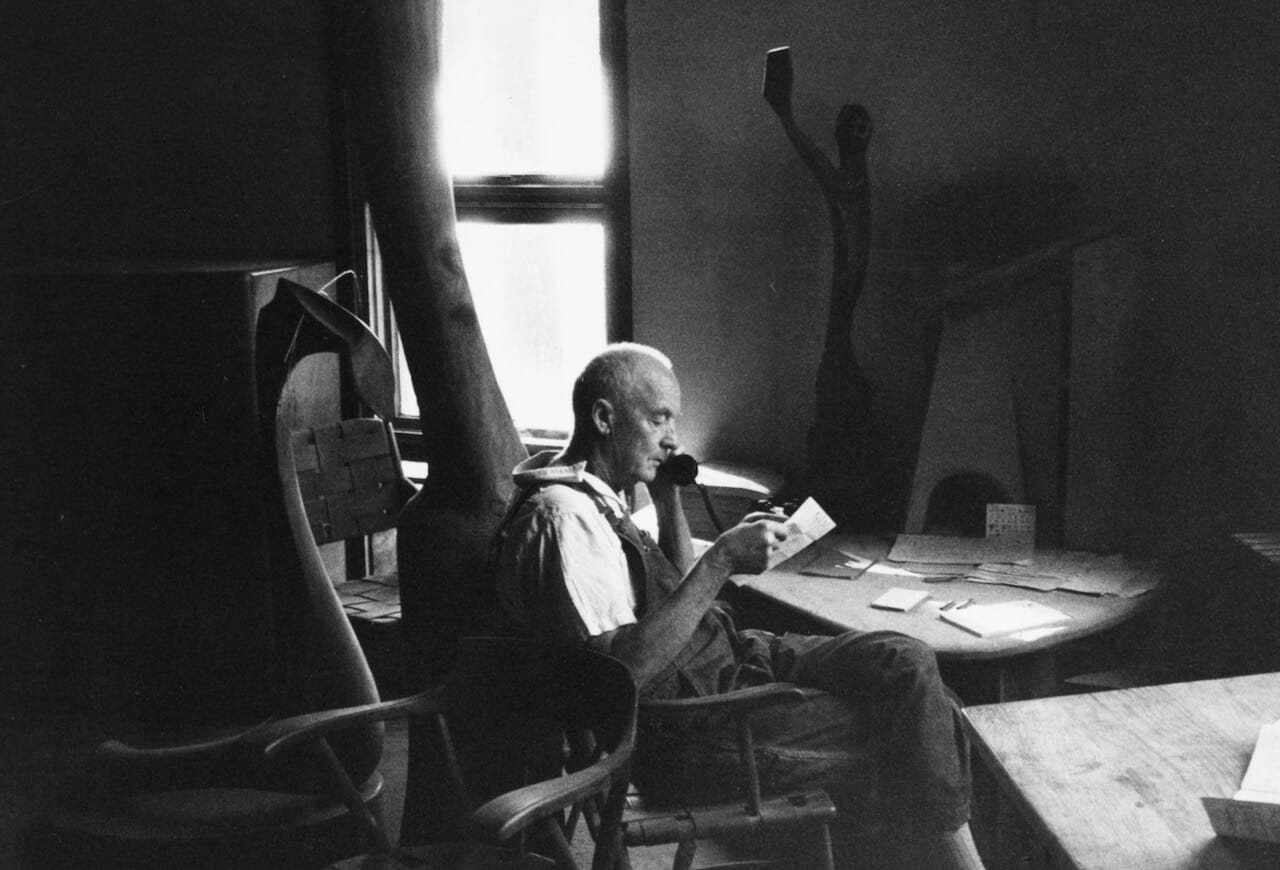

Wharton Esherick outside the Workshop, 1961. At right is his log cabin garage (1928), to which the Workshop abutted.

Archival photographs of Esherick in the Workshop support Hartshaw’s description. Furthermore, the images show that Esherick used the Workshop as a gallery, dedicating large swaths of floorspace to exhibiting his completed sculpture and furniture. This arrangement meant that Esherick could show his work to visitors without inviting them into his private living quarters within the Studio.

In the Studio, Esherick lived amidst his art, surrounded by his sculpture, furniture, prints, paintings, and ceramics. Because the building was itself an inhabitable artwork, it is possible to say without exaggeration that Esherick made his art his home. But his relationship to the business end of his furniture making was another story. The twenty-step walk from the Studio to the Workshop was a short commute, but a commute nonetheless. This physical separation, reinforced by a windowless concrete wall, suggests that Esherick found that work—with all its facets taken into consideration—was uninhabitable.

Written by Director of Interpretation and Research Holly Gore

April 2022