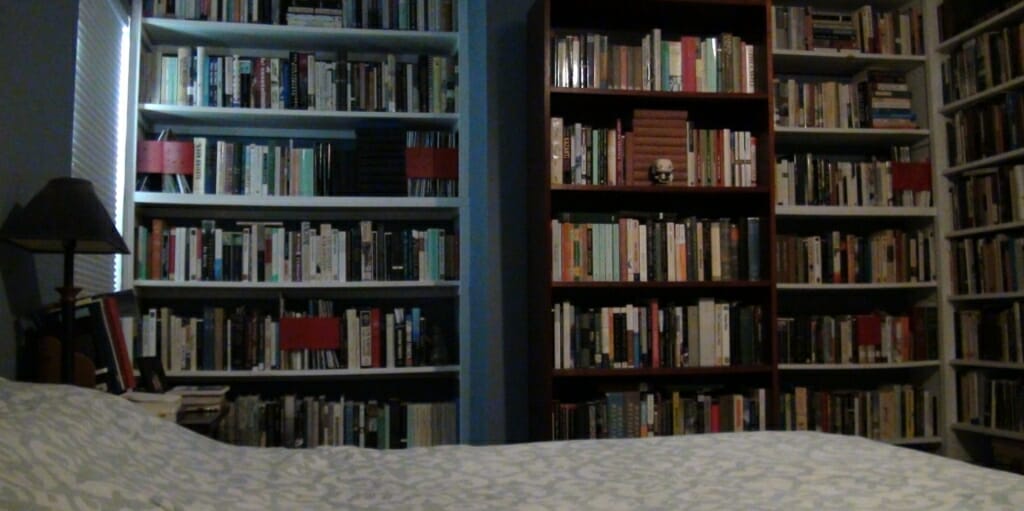

Solid wood — and sometimes curving — bookshelves line the walls of Wharton’s bedroom.

This month we are delighted to share the reflections of Ron McColl. Ron first visited the Wharton Esherick Museum more than twenty years ago. From then on, he was a devotee. In 2014, he became a docent; in 2017, he joined the Board of Directors. With a background in English literature, library science, and book history, Ron has volunteered with the Museum to deepen our understanding of Wharton’s library. He has spent countless hours leafing through the books on Wharton’s shelves. Ron is the Special Collections Librarian at West Chester University and lives in Schwenksville, PA with his son, Liam, and his wife and best friend, Lisa.

I have come to be in Wharton’s house many times; we know each other now, and so it too has come to be in me.

Inside, and up that tree of stairs—its railing like a rain smooth palm to take my own—I know the books on Wharton’s shelves. I see their earth tone spines, denuded of their glossy jackets and made to stay a while. They are all there, his friends. The life-worn Dreiser who never got ahead, or stayed ahead, or knew what it meant to be ahead when he was. The artful Anderson, who gave his gifts to lesser men who then made with them bigger names for themselves. The inward Toomer, so seeking he stepped outside his own race after giving issue to its renaissance. They were all pity-driven and reckless and aiming and faltering; and so they wrote beautiful books, denuded of the glossy world and here to stay a while. It did not show on paper, but all the while Wharton was writing, too.

He wrote the entire world into that house. I know because I have walked about it and it is in me now when I am not there. If you have ever been there, and perhaps long for it now, you will find it again in all the great books. In Melville, you see it in a storm, the neat set row of bedroom panes battered by a mountain hail; in Proust, you run your hands along the undulating edges of those kidney-shaped tables and taper into time and back again; in Ellison, you see Wharton himself, invisible in his hovel, jiving to his own Armstrong, blasting the light fantastic, and damning the fabricated world; in Fitzgerald, you see all the house repels; in Cather, you see just how it was meant to stake the land; in Thoreau, you realize that it is no house at all–just a man making something out of nothing of himself.

We know great writers when we read them. The joints are all hidden, the words have done the work of each of their neighbors, and the earnest paragraphs carry awful and beautiful truths in rhythmic step. Wharton worked this way, too. He ran the chain up to the rigging of the joists; he barked at Ed Ray’s flatbed truck until it stopped before those open eagle-bearing doors; he hoisted slabs of Chester County’s walnut, oak, and cherry into the mouth of that house. You can see for yourself what he did next; it is written everywhere you look. Like all else about the place, there is a poem in that desk of curly oak if you would open it. Even the always haunting receipt book he kept in it–and it is still there feverishly anticipating an account received–bows to the yawp of that desk’s art.

In Wharton’s house, dovetails abound, but must perform their prim purpose amid angles set against the grain. He swooped arcs in wood that only birds describe. He wrote a thousand stories in the colors, knots, and unplaned boards–a rich majesty of both the rough and the tumbled stone.

If you go to Wharton’s house, you may recognize someone you know in all that craft. I can even see my father there. He is still alive and with his own practical hands he too is fashioning something. It will be cruder than Wharton’s work, but it too will be literature. It will be honest, and it will last, and it will serve a purpose. And to think I never took him there; he just knew the same stories as Wharton.

I look at my own shelves and am heartened to see that I have many great books left to read, and many more to read again. And so I can always visit Wharton’s house.

But you should come and see it for yourself. They have tried to make a museum of the place, though I don’t know if they have actually succeeded or not. I doubt any vital soul can visit the place and not feel at home instead.

Mere museums are not made to do that kind of thing.

Like Wharton, Ron shares his bedroom with many books.

Post written by WEM devotee, docent, and Board Member, Ron McColl.

September 2020