September 26, 2024 – December 29, 2024

Rhythms of Work brings together artifacts of Wharton Esherick’s studio practice to highlight his approach to furniture making as fundamentally collaborative and open to modern technologies. Best known for his sculptural wood furniture, Esherick practiced handicraft without idealizing it, frequently relying on the skill sets of others to realize his creative vision.

Drawn from WEM collections, Rhythms of Work includes a selection of Esherick’s tools, works-in-progress, and personal papers. The exhibition also features rare moving-image footage of Esherick, excerpted from an amateur film made in 1958 by Robert Laurer, who was then the Assistant Director of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York (now the Museum of Arts and Design). The tools that are on view belonged to Esherick at the end of his life, after which time they went to his employee, woodworker Horace Hartshaw. The Museum is grateful to Eric Hartshaw, Horace’s son, for his recent gift of these tools to WEM.

This installation will be on view in our Visitor Center, which is open during our current tour hours. Please note, guests wishing to enter the Studio must make advance reservations for a tour.

What does it mean to build furniture as an artist? This line of thinking runs through the career of Wharton Esherick (1887-1970). Best known for his wood furnishings that marry function and expressiveness, Esherick innovated new rhythms of work as he crafted his sculptural designs. Hand wrought details are a signature element of Esherick’s functional artworks, yet he never idealized handicraft. Esherick embraced the speed and heft of power tools at the same time as he kept his kept his axe blade sharp for the body-driven work of hewing sculptural forms.

This exhibition brings together a selection of artifacts that bear witness to the rhythms of Esherick’s practice—in his hand-built Studio where he worked alone, in his nearby Workshop where highly skilled cabinetmakers collaborated with him to realize his designs, and in the world beyond, where he teamed together with museum curators and exhibit builders to bring his creative vision to national and international audiences.

Many of the objects on view in this room belonged to Horace Hartshaw, a furniture maker and building contractor who worked for Esherick in the 1960s. Hartshaw was one of several cabinetmakers whom Esherick employed to build his designs, but was the only person entrusted to execute Esherick’s unique sculptural details, such as fluid curves and and rounded, tactile forms. After Esherick died, his family gave most of the tools in his shop to Hartshaw and another of his workers, Bill McIntyre. The Wharton Esherick Museum is grateful to Eric Hartshaw, Horace’s son, for his recent gift of tools and other objects that his father had acquired from the Esherick Workshop.

Pictured right: Hand Saws (circa 1910-20 and 1940s)

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Eric Hartshaw

Mine can hardly be termed an “industrial operation.” I am a sculptor, who makes sculpture and commissioned sculptural furniture and crafts—original pieces, which are made one or only a few at a time. I work in my studio, and the 2 employees are my helpers. I am known as an artist.

-Wharton Esherick

Stanley “Everlasting” Chisels

20th century

Stanley Tools

Steel, wood

As with all of the tools hanging on the wall, these chisels belonged to Wharton Esherick. Horace Hartshaw, who worked for Esherick from 1960 on, acquired them after Esherick’s passing in 1970.

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Eric Hartshaw

Right:

Hand Saw

Circa 1940s

Diston Company

Steel, wood

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Eric Hartshaw

Left:

Hand Saw

Circa 1910-20

Sargent Company

Steel, wood

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Eric Hartshaw

Broadaxe

Circa 20th century

Manufacturer unknown

Steel, wood

The metal head of this broadaxe belonged to Wharton Esherick. The wood handle is a later addition, made by Horace Hartshaw in the 1980s. The broadaxe was one of several types of axes that Esherick used to shape his sculptures and sculptural furnishings.

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Eric Hartshaw

Two-Step Ladder, unfinished

Designed 1962, built circa 1960s

Wharton Esherick, designer; Horace Hartshaw, builder

Walnut, cherry

Horace Hartshaw created the components for this partially complete rendition of Esherick’s Two-Step Ladder. The design was one that Esherick’s shop produced as a limited edition–a scenario in which the furniture makers often created spare parts to ensure the job was completed economically. The reasons that this Two-Step Ladder was never finished are unknown. But it is possible that the ladder on view–which Museum staff have dry assembled without any glue–is made entirely of spare parts.

In its design and construction, Two-Step Ladder resembles Esherick’s Wishbone Chair (displayed beside it on the platform). Thus, this unfinished piece gives clues to the process of making the completed Wishbone Chair.

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Eric Hartshaw

Wishbone Chair

1959

Wharton Esherick, designer

Cherry, painted fabric

Wharton Esherick designed Wishbone Chair in 1958 as part of a dining set for his patrons Dena and Jim Dannenberg, who lived in the Philadelphia neighborhood of Mt. Airy. The piece was a variant of his earlier S-K Chair (1942), which he had created for a corporate boardroom.

This 1959 rendition of the design was likely built by his sole employee at the time, Bill McIntyre. A neighbor who lived on nearby Jug Hollow Road, McIntyre learned the trade of furniture making from an earlier collaborator of Esherick, the Hungarian American cabinetmaker John Schmidt.

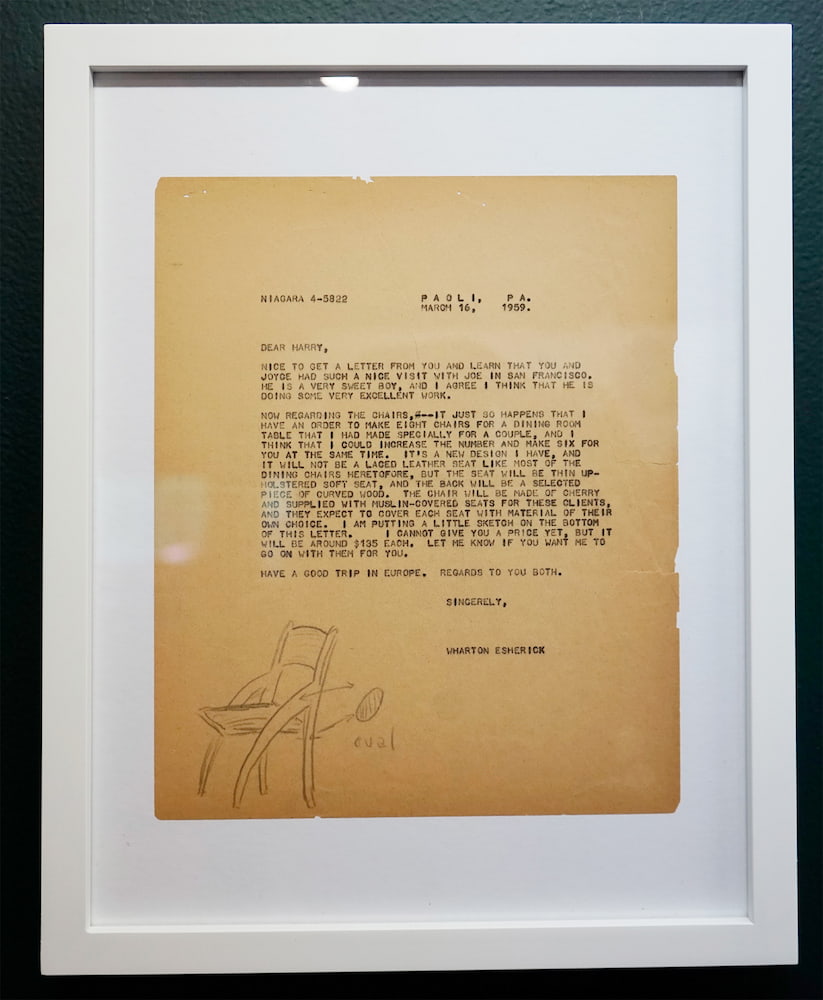

Carbon copy of a letter from Wharton Esherick to Harry De Silver

1958

Ink on paper

Esherick manufactured his furniture designs as one-of-a-kind objects or in limited runs of approximately ten to twenty pieces. With this letter, he sought to make the most of a new design by making two sets of identical chairs simultaneously, thereby increasing his efficiency.

Wharton Esherick Museum

The photograph reproduced at left (courtesy of Eric Hartshaw) shows Horace Hartshaw in his workshop in 2009.

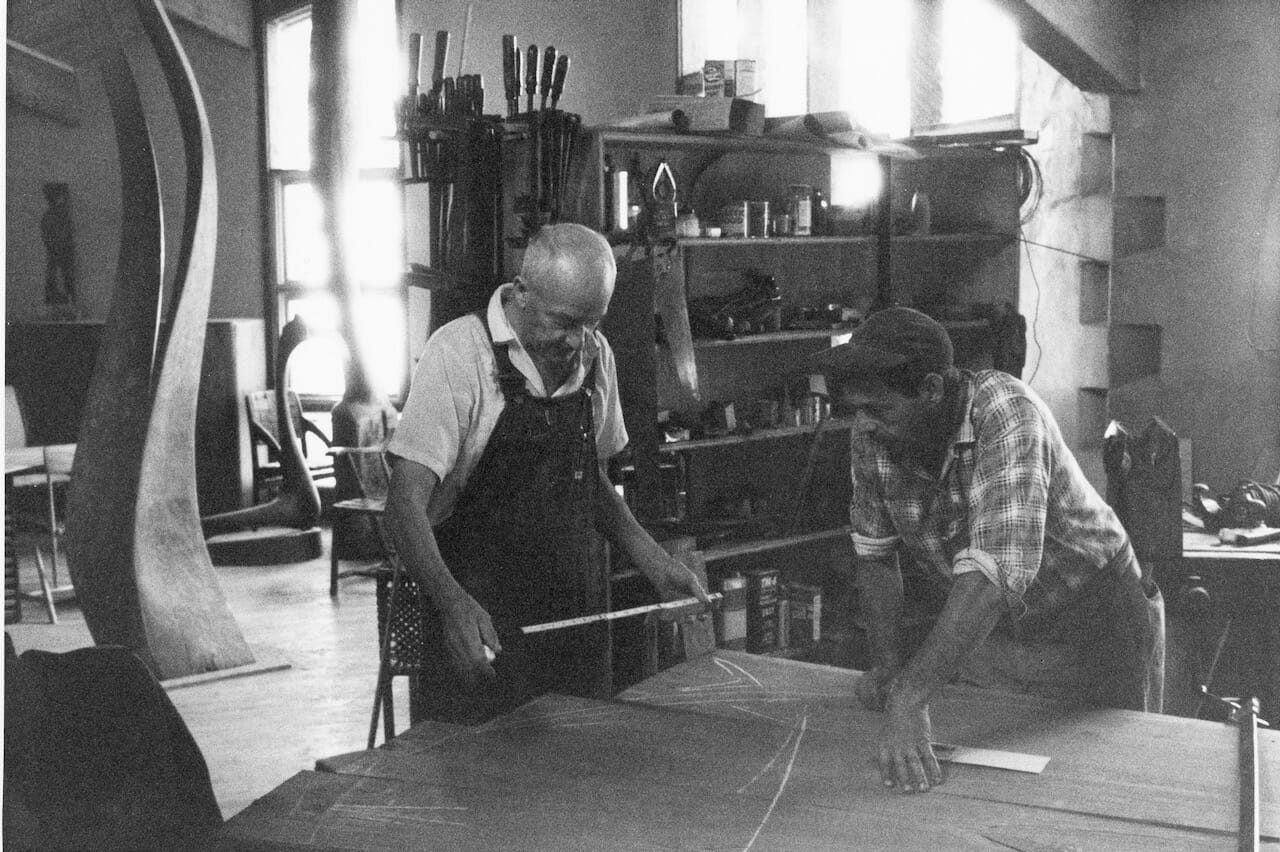

The photograph reproduced above shows Esherick and Bill McIntyre at work on the Dannenberg dining table in 1958.

Skil Drill

Circa 1950s

Skilsaw, Inc., Chicago

Metal, electronics

Power tools, such as this heavy-duty drill, quickened the flow of Esherick’s furniture production. Horace Hartshaw remembered that when he began working in Esherick’s shop in 1960, Esherick had some power tools: a router, jointer, and two bandsaws. Hartshaw, with a background in home building and a mind for efficiency, recommended to Esherick that he buy more machinery. Subsequent power tool purchases included a table saw, planer, radial arm saw, belt sanders, and a chainsaw.

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Eric Hartshaw

Stair Tread

1963

Wharton Esherick, designer

White oak

This stair tread is a spare part from a spiral staircase that Wharton Esherick built for a home in Pittsford, New York. The homeowner, Michael Watson, visited the Esherick Studio, fell in love with Esherick’s iconic 1930 Red Oak Spiral Staircase, and asked the artist to build him a copy for his house. Esherick agreed to make a staircase that was similar. The resulting piece had smoother contours than the original. But the overall geometry was near-identical. Watson disliked the new design and only reluctantly accepted it.

The video below, which documents the assembly of the 1930 Red Oak Spiral Staircase, sheds light on the way in which this individual component would have fit within the whole of the staircase.

Wharton Esherick Museum, bequest of Mansfield Bascom

Installing “The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick” at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York

1958

Robert Laurer

Digitized 8mm film

This film is a seven-minute-long silent movie that curator Robert Laurer made during the installation of Esherick’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (MCC), “The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick.” The focal point of the film is the installation of Esherick’s Red Oak Spiral Staircase, which Esherick built for his Studio in 1930. For the exhibition, the staircase was disassembled, shipped to New York, and reassembled at the MCC.

In the film, Esherick (the tall man in the dark suit with close-cropped hair) works alongside curators and other museum employees to install the staircase. Intermittently, the camera cuts to other workers in the room, including carpenters, exhibit fabricators, curators, an art critic, and MCC founder Aileen Osborn Webb (in the fur coat).

The Laurer film is the only extant moving image footage of Wharton Esherick.

Wharton Esherick Museum, gift of Robert Laurer