Ford Madox Ford, poet and novelist. Image c. 1905, in the public domain via Wikimedia.

In honor of National Poetry Month, we took a look at the poets found in Wharton’s library. On the shelves we found works by Walt Whitman, Robert Frost, Gavin Maxwell, Robinson Jeffers, William Carlos Williams and more. What stood out were two volumes of poetry by Wharton’s friend Ford Madox Ford — New Poems, and Collected Poems of Ford Madox Ford.

Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939), a native of Britain, was born Ford Hermann Hueffer on December 17, 1873 in Surrey. Early in WWI, Ford worked for the War Propaganda Bureau where he wrote two propaganda books. After their publication, he enlisted in the Welch Regiment and was deployed to France. His experiences on the war front and with the propaganda department inspired Parade’s End (1924-1928), which was recently made into a BBC mini-series starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Rebecca Hall. It was broadcast on HBO in the United States early this year. In his lifetime, Ford would write over 50 books and count among his friends many of the literary giants including James Joyce, Ernest Hemmingway, Gertrude Stein, Theodore Dreiser and Jean Rhys.

Wharton was introduced to Ford through Theodore Dreiser, who sent Ford and his lover Janice Biala, to visit Wharton after they had visited Dreiser at his home in Mount Kisco, NY in the fall of 1934. While they were there, Wharton taught Biala how to carve woodcuts, and she painted a study of Wharton’s daughter Mary that is currently on display in Wharton’s bedroom. While Biala painted and learned to carve, Ford worked on his novel Great Trade Route; he wrote sitting at Wharton’s 1929 Flat-Top Desk (the Sawhorse Desk). Ford included a description of his visit to Wharton’s studio in Great Trade Route:

“A dim studio in which blocks of rare woods, carver’s tools, medieval looking gadgets, looms, printing presses, rise up like ghosts in the twilight while the slow fire dies in the brands…Such a studio built by the craftsman’s own hands out of chunks of rock and great balks of timber, sinking back into the quiet wood on a quiet crag with, below its long windows, quiet fields parceled out by the string-courses of hedges and running to a quietly rising horizon…such a quiet spot is the best place to think in.” You can read more of his description from Great Trade Route in the front of Wharton Esherick Studio and Collection (available in our gift shop and online store).

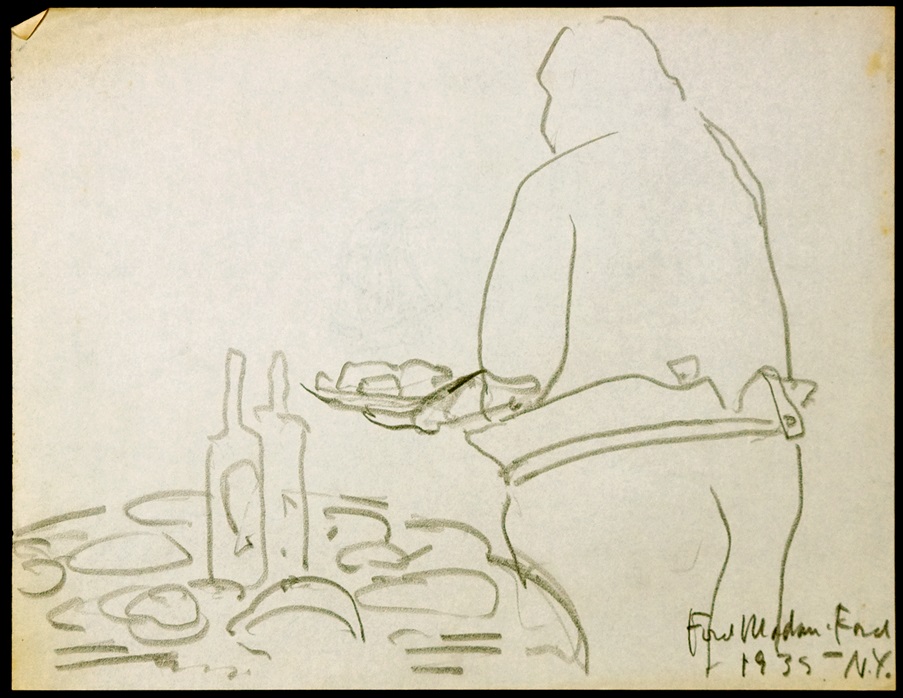

Wharton’s daughter Ruth remembers Ford’s visit. He was a gourmet cook, and her mother, Lettie, encourages her to learn from Ford. Wharton sketched Ford serving everyone.

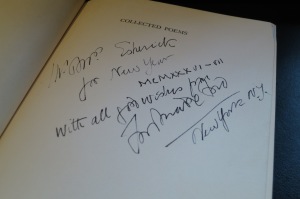

On the title page of Collected Poems of Ford Madox Ford, (printed in 1936), is an inscribed message: “Mr. Mrs. Esherick for New Year MCMXXXVI-VII with all good wishes from Ford Madox Ford New York, N.Y.”. The volume is made up of 112 of his poems, including quite a few he wrote while on active service during WWI. According to the introduction of Collected Poems, “Mr. Ford professes to be ill-read in English poetry and not to care much about it. This is partly an attitude. He is a born romancer.”

Perhaps his best known poem is called Antwerp, which was written in 1915 (before he changed his name) about why the Belgians resisted the invading German forces making their way to France during WWI; it is included in this volume. We discovered an original publication of the poem tucked in the front cover, perhaps by Wharton. T.S. Eliot said this poem was “the only good poem I have met on the subject of the war”, it is also Ford’s favorite poem written during active service.

Antwerp

I

Gloom!

An October like November;

August a hundred thousand hours,

And all September,

A hundred thousand, dragging sunlit days,

And half October, like a thousand years…

And doom!

That then was Antwerp…

In the name of God,

How could they do it?

Those souls that usually dived

Into the dirty caverns of mines;

Who usually hived

In whitened hovels; under ragged poplars;

Who dragged muddy shovels, over the grassy mud,

Lumbering to work over the greasy sods…

Those men there, with the appearances of clods

Were the bravest men that a usually listless priest of God

Ever shrived…

And it is not for us to make them an anthem.

If we found words there would come no wind that would

fan them

To a tune that the trumpets might blow it,

Shrill through the heaven that’s ours or yet Allah’s

Or the wide halls of any Valhallas.

We can make no such anthem. So that all that is our

For inditing in sonnets, pantoums, elegiacs, or lays

Is this:

‘In the name of God, how could they do it?’

Thanks for stopping by, continue Reading Antwerp here.

More poetry by Ford Madox Ford.

Post by Assistant Curator, Laura Heemer.