Unless otherwise noted, all quotes in this blog post were taken from oral history transcripts in the Wharton Esherick Museum archives. The interview of George and Gene Rochberg was conducted on June 5, 1987 by Susan Hinkel. Our oral histories are available to scholars and researchers by request. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

“Wharton had passed beyond just thinking or feeling or talking art; he was as much a part of what we call “art” as art was a part of him, like the trees that grow around this hilltop – naturally, unselfconsciously.”

The composer George Rochberg (1918-2005) spoke these words at our Museum’s Twentieth Anniversary Members’ Party nearly thirty years ago, articulating a quality about Wharton Esherick that resonates even with those of us who only know him through his work. Rochberg’s eloquent reflection prompted us to dive into the Museum’s oral histories this month to learn more about the relationship between the Rochbergs and Esherick. Gathered in the 1980s in preparation for writing Esherick’s biography, these conversations offer new perspectives on Esherick’s life and legacy.

George Rochberg and his wife Gene were friends of Esherick’s for some 30 years. Rochberg was an accomplished artist himself, completing over a hundred pieces of music, including six symphonies, seven string quartets, and an opera. He even dedicated one piece – the music for “The Alchemist,” a play by Ben Johnson performed at the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center in New York – “to my dear friends Wharton Esherick and Mima Phillips.”

The Studio with a packed earth floor. XX stands in the foreground, Love and/or Hate hangs on a chain hoist, and Adolescence stands in the distance. Photo by Consuelo Kanaga.

The ‘Mima,’ included in this dedication is Miriam Phillips, Wharton’s partner for the latter half of his life. It was through Miriam and Gene Rochberg that the two couples became friends; in the 1940s, Gene was a member of Miriam’s acting class. One class treat was a trip to Paoli to perform a play and enjoy a cookout at Esherick’s studio. Gene later recalled “the journey into the wilderness” back when the studio had a dirt floor and her awe of Esherick and his work.

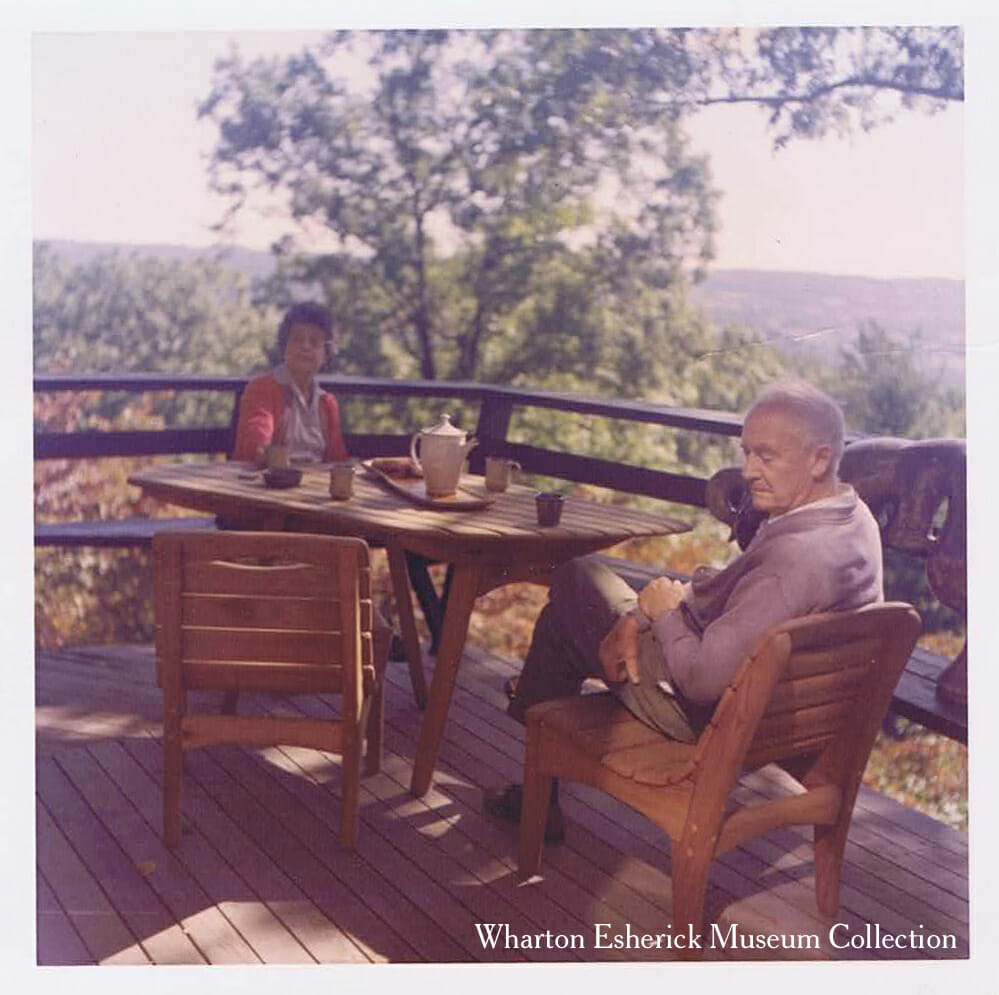

The two couples hit it off. One of their rowdier stories involved a steady flow of Jim Beam and Miriam shrieking as Wharton dragged the broiler and bloody steaks from the fireplace, where he had cooked them, upstairs to the dining room. Other visits were spent sitting out on the deck, the Rochbergs keenly aware of Esherick’s kinship with his surroundings.

Though they came from different generations, the unorthodoxy of their creative lives drew them together. Esherick was also an avid fan of classical music and deeply interested in the process of composing. The younger couple seemed to learn a great deal from Esherick’s modesty and unfettered pursuit of his art. As Gene reflected, “We learned a lot about what happens to an artist who lives a long time. We could see that he had been famous, forgotten, famous again, shelved …and he did very little to advance his own cause. Whatever came to him was the result of the beauty and excellence of his work.”

George felt the same, “[Wharton] was not your typical self-ballyhooing artist… He struck me as totally integrated as a human being. He may have had his private neuroses but they were not evident, because he had a wonderful attitude toward existence. He could joke and make light of a lot of serious things and yet you knew that underneath all that joking was great seriousness… It was really a lesson in more ways than I can even articulate to be with a man who was unselfconscious about his relation to his work and so far from self-promoting himself.” These sentiments ring true with Esherick’s nephew and celebrated architect Joseph Esherick’s statement at another Annual Members’ Party: [Wharton] had no axe to grind for any movement other than honesty.

In the oral history, Rochberg is careful not to suggest that he achieved an Esherick-like way about his own life. Conversely, many of Rochberg’s stories revolved around how much he would espouse his ideas, considering himself a great arguer and eager to engage in rigorous conversation, to which Esherick would tease, “You’re either the bravest or the most foolish man I ever met!”

Rochberg was known for bucking expectations in his field, willing to go against the grain in pursuit of his self-expression. He was criticized for abandoning the modernism of his earlier works – which were in line with avant-garde mid-century movements – and returning to more traditional approaches in the 1960s after the death of his teenage son. For Rochberg, the atonal qualities of his earlier style were too limiting and lacked the expressiveness he desired. However his music hits your ear, it is clear that Rochberg was on an earnest search for authenticity, and that seems like a trait Esherick would have admired. It was certainly part of what Rochberg admired in Esherick.

“[Wharton] had a kind of cleanliness of spirit, mind, and person which is pretty rare… He refused to remain attached to anything that he felt for any reason did not belong to him. So whether it was religion or New York or whatever it was, when the time came after a crucial experience, he would shed, and in that way he didn’t drag baggage with him through his days… he stayed an airy spirit.”

Learn more about our archives.

Listen to George Rochberg’s String Quartet No. 3 – Part C

Written by Communications & Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

February 2020