March 2, 2023 – May 14, 2023

Throughout 2023, our programs, exhibitions, and events will showcase the important role storytelling played in Esherick’s life – and the fuller picture these stories can offer about who Esherick was in the varied aspects of his life – as artist, father, friend, and more. Each object in the collection of the Wharton Esherick Museum (WEM) – from major pieces of sculpture and furniture to the unassuming ephemera hidden in drawers and cabinets – holds within it myriad stories. Some of the stories these objects hold center around making and designing. Others may highlight the ways in which these pieces were used and viewed by the people who came into contact with them. Once an object becomes part of a collection, to be viewed by the public, it tells yet another story.

This installation will be on view in our Visitor Center, which is open during our current tour hours. Please note, guests wishing to enter the Studio must make advance reservations for a tour.

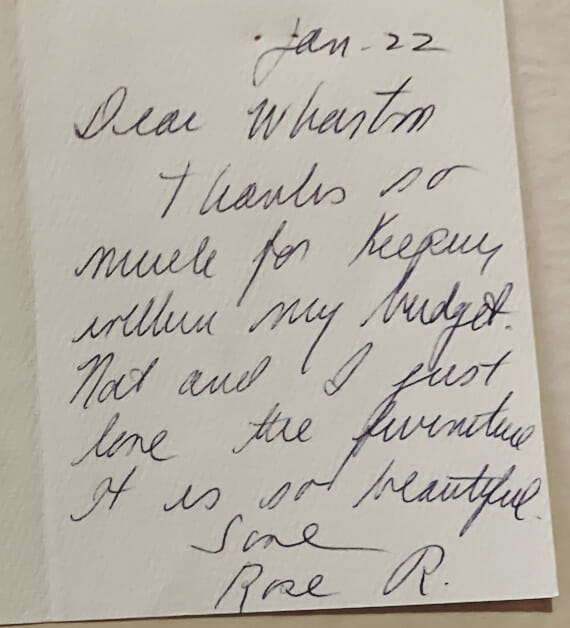

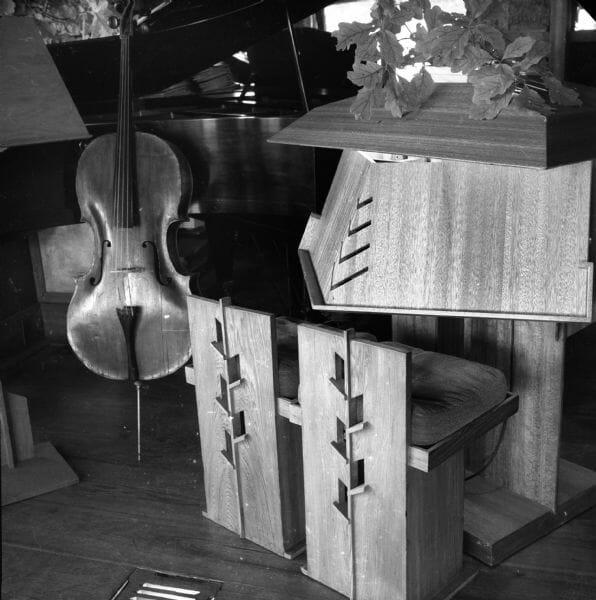

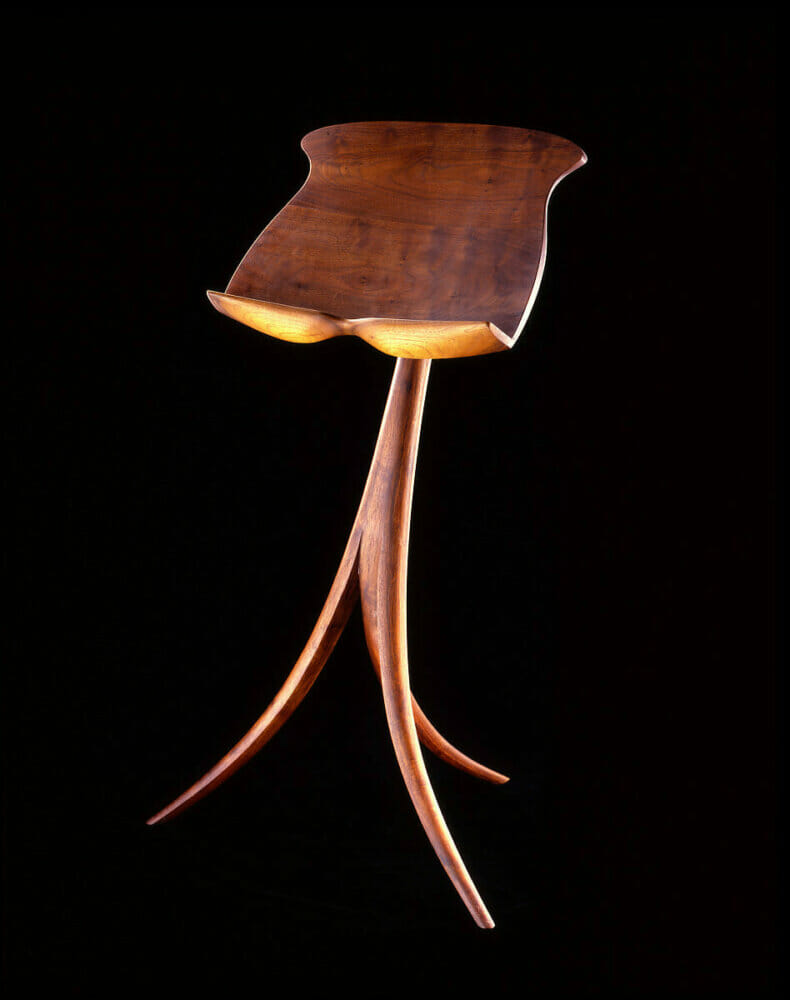

One Object, Many Stories offers a deep dive into one of Esherick’s most well known sculptural furniture forms: the music stand. This particular music stand was built for Rose Rubinson who, along with her husband Nathan (Nat), was one of Esherick’s most significant patrons in the 1950s and 1960s. They commissioned Esherick to produce a household’s worth of furnishings for their residence, beginning with this music stand for Rose, a cellist.

Esherick and the Rubinsons’ friendship lasted for three decades. That friendship is just one of the narratives that examining the Rubinson’s music stand offers to us as viewers. Others include Esherick’s stylistic language, influences, process, and context at mid-century; how Rose Rubinson’s music stand became the impetus for new designs for Esherick; and the use of this object in several exhibitions, both domestic and international, that would define Esherick’s career and legacy.

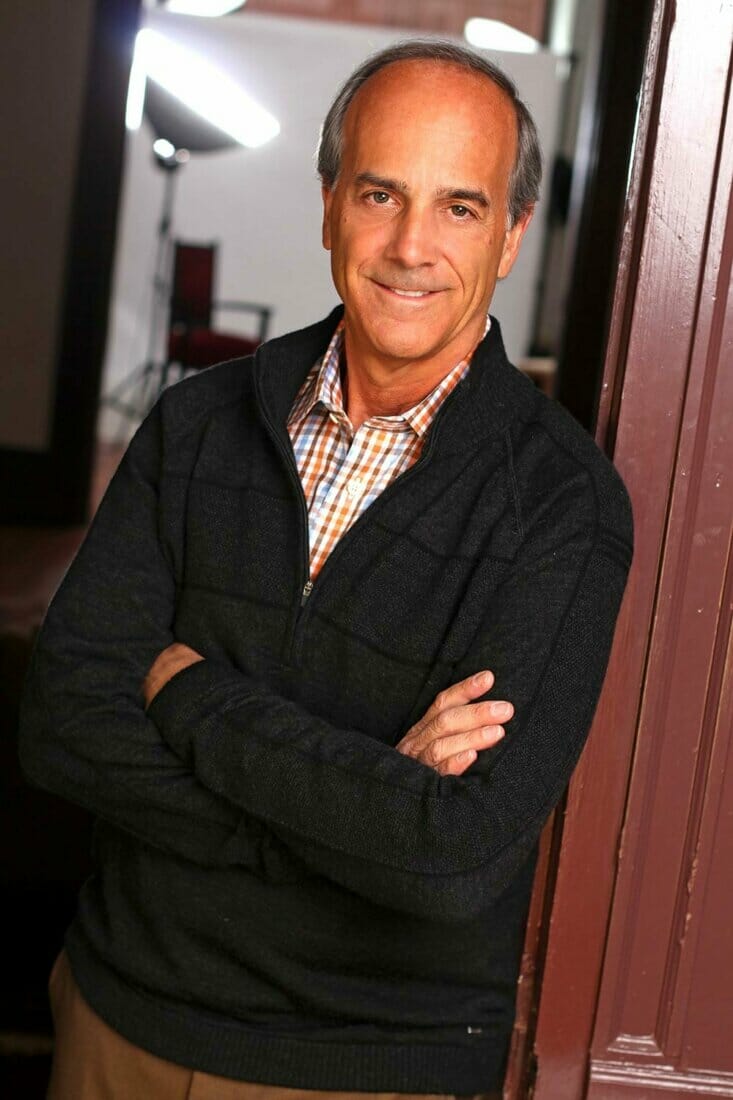

WEM is fortunate to have the prototype music stand made for Rose Rubinson on view in our Visitor Center through the generosity of Geoffrey Berwind, grandson of Nat and Rose and a member of the Museum’s Board of Directors. We are not only thrilled to have the opportunity to share this wonderful work with our visitors, but also to honor the continued involvement of the Rubinson/Berwind Family in preserving and celebrating Esherick’s legacy since the museum’s founding in 1972.

The Rubinson Home

Nat and Rose Rubinson’s journey with Wharton Esherick began with a salad bowl. In an oral history, Rose recounts a narrative of their first visit to the Studio:

And before we left that day, I said to Wharton we wanted a salad bowl and we’ll be back. Well, thirty years later with a houseful of furniture, we never got the salad bowl.

In the image of the Rubinson home pictured here, we can see just how thoroughly their collaboration with Wharton transformed their living spaces. At first, Nat and Rose wanted Esherick to make a piano. While this didn’t materialize, it did lead to a piano bench, followed by a commission for an organic dining room table. Custom sideboards, shelving and cabinets topped with Esherick’s sculptural works, and a sofa upholstered in the artist’s signature deep red color reflect only a portion of the works alongside which Nat and Rose lived their lives. An exhaustive collection of Esherick’s prints and other works on paper, including drawings that represent their deep friendship, were also a part of their collection.

Nat and Rose’s deep trust in Wharton guided their acquisition of and life with his work. As Rose recounted:

In fact, every time he made us something, Nat never asked. He was the artist and we thought he was the most wonderful artist in the world…

The Musician and the Music Stand

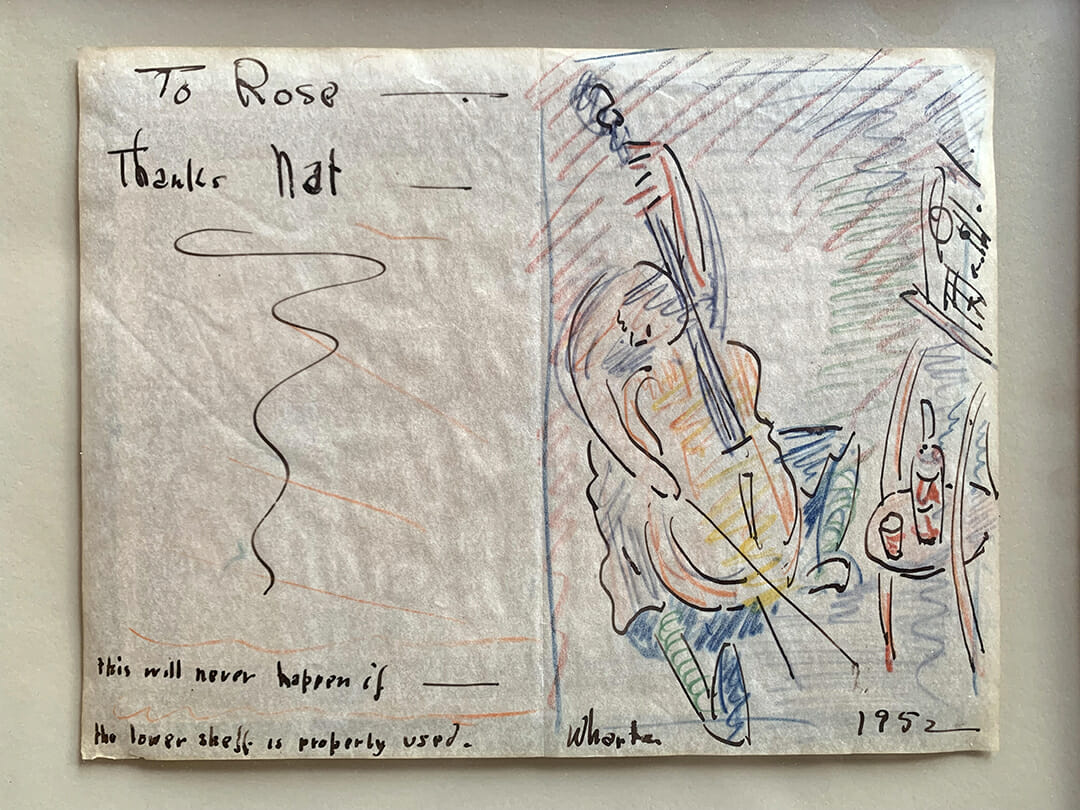

Rose Rubinson’s passion for music inspired the creation of one of Esherick’s best-known and most celebrated objects. Esherick’s framed cartoon of Rose playing is a testament to just how much her needs were central to his conception of this now-iconic form. The three legs of the stand are braced by a triangular shelf, included not to hold Rose’s musical paraphernalia, but “for a little snifter in case you feel faint during a performance.”

Rose’s music stand was such a success that, together, the three envisioned their potential to be made in a limited production run of 24 objects. However, the magic of the original was hard to recapture. Rose recounts in an oral history:

So we had 100 parts made up so you could assemble the music stands, and then I saw that one can never never duplicate creativity in an artistic endeavor into a commercial product with the artist. Nonetheless, Esherick’s design and voice remained strong, even when manufactured in a series. For example, works from this limited production run appear in major collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Other elements that Esherick later created for the Rubinson home reflect his interest in designing a space that supported Rose’s musical life. He produced two reposition-able swinging lights – similar to those in the Studio – after Rose told him that she was hosting string quartets in the middle of the room, and side lamps proved insufficient. Rose’s music governed their relationship from start to finish. The last element that Esherick created for the Rubinsons was an arm-like mount to hold Rose’s cello up on the wall, which he was working on when he passed away in 1970.

A Lasting Friendship

The relationship that Wharton Esherick had with Rose and Nat Rubinson went far beyond that which Esherick had with most of his clients. Theirs was a deep and intimate friendship, even outside of the remarkable trust that the Rubinsons placed in Esherick to build their world. Rose recounts in an oral history that while having a conversation at a party, she mentioned that Wharton Esherick was making a chest of drawers for the Rubinson home. Rose’s conversation partner responded by saying:

“Wharton Esherick? He must like you.”

I said, “Why do you say that?”

“He won’t make anything for anyone he doesn’t like.”

So the next time I saw Wharton I told him the story, and he said, “She’s right.”

Rose and Nat invited Esherick to travel with them but he declined, noting that he hadn’t “fully explored his woods yet.” The Rubinsons instead spent a great deal of time with Esherick at his Studio, at his behest. The two rarely initiated social visits with Esherick but instead waited for his calls, which often came when he was between projects and ready to socialize.

Nat and Rose often joined Esherick for meals up on the mountain. They ate steaks on plates and bowls made by another member of the inner circle, the ceramist Franz Wildenhain. Esherick’s memorial service coincided with another special meal, a dinner made by his daughter Ruth.

Nat and Rose recount the evening in an oral history that both speaks to that melancholy moment, but also to the many gatherings they held with Wharton at the Studio:

We all sat out on the porch, and we all told different anecdotes that happened to us with Wharton: charming stories. And then they opened a bottle of champagne and passed it around and we all took our glasses and toasted, “To Wharton,” lifting them to the sky. And it was dusk. And it was the most beautiful memorial service. And it was very gay, because we knew that was what Wharton would have wanted. There were no tears.

The Music Stand Meets the World

While the original home for Esherick’s music stand was with the Rubinsons, its display became more expansive and public. In the late 1950s and 1960s, there were several ways to encounter the music stand besides procuring an invitation to one of Rose’s in- home recitals. Aileen Osborne Webb, the philanthropist who founded the American Craft Council (ACC), invited Esherick to participate in the American Pavilion at Expo 58 in Brussels. As the first World’s Fair following the Second World War, the Expo was themed around the “evaluation of the world for a more humane world” and attracted over 41 million visitors to 45 national pavilions. The American pavilion featured a section organized and promoted by the ACC that marked the first time American crafts were included at a World’s Fair.

Esherick’s music stand was one of 130 pieces by 75 American craft artists on display representing the power of craft and craftsmanship in shaping a new and more humane world after the terrors of the previous decade. As Webb wrote in her invitation to Esherick, which is now part of WEM’s archival collections:

In this age of Sputniks, the humanistic values of a country’s craft culture are more important than ever. The finest possible work must be made available for foreign showings. The ACC is confident that the craftsmen of the U.S.A. in cooperation with our government agencies will meet this challenge.

While the Expo represents the most exposure the music stand received, it is not the only way it met the world shortly after its making. For example, the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) included the music stand in the retrospective exhibition The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick (1958-1959).

The Music Stand in Context

The music stand has a long and rich history against which Esherick could position his efforts. While the earliest evidence of music stands can be found in China as early as 200 BCE, they emerged in Europe significantly later; musicians there typically improvised or played from memory, and machine-printed music was only available starting in the 15th century, about 20 years after the invention of the printing press. The first music stands used in Europe were table-top versions, followed by floor-standing examples in the 17th century. Just as Esherick created a highly specific form to meet the needs of his client, so too did French designers and furniture makers, who created music stands that were adjustable, had extending arms intended to hold candles for illumination, or had lavish decorations so that the stand would integrate into its larger environment. Later, artist and architect contemporaries of Esherick’s such as Frank Lloyd Wright designed their own versions of the form. Wright’s quartet stands feature a removable tray with a space to show a small artwork or vase of flowers.

In 1951, when Esherick produced his first music stand, he was also hard at work on his prototype for his version of a traditional Captain’s Chair. This became one of Esherick’s most marketable pieces, aimed at the increasing number of people interested in furnishing their homes with contemporary, artist-made objects. Esherick also made these chairs in a limited production run, with much greater success. The Captain’s Chair possesses a more constrained energy than the music stand, whose design lyrically embodies music itself. Esherick’s style in the 1960s ultimately had more in common with the music stand’s organic and biomorphic composition.

Influence and Legacy

While this music stand was Esherick’s first, it was far from his last. Instead, it became a signature form and had an outsized influence on other furniture makers seeking to intertwine function and artistry. Other musicians commissioned Esherick to produce music stands for their own personal use. He produced versions of the single music stand for practitioners including Sol Sumergrad, a jazz musician, and his dear friend George Rochberg, a composer of contemporary classical music who also chaired the Music Department at the University of Pennsylvania. Rochberg and Nat Rubinson were both instrumental to the foundation of WEM as two of the five original directors noted on the museum’s articles of incorporation. Esherick also created a double version of the music stand for Herbert Koslow – an insurance industry professional as well as a flutist and classical singer – to use while playing alongside his wife.

This elegant variation on a theme was featured in WoodenWorks, the inaugural exhibition of the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1972. In that show, Esherick posthumously shared the stage with artists of a younger generation, including Art Carpenter, Wendell Castle, and Sam Maloof, whose own versions of the music stand form visually resonate with his earlier example. Castle, for example, visited Esherick at his Studio in 1958 shortly after learning about his work and credits him with opening his eyes to the potential of furniture to be art. His version of the music stand demonstrates Esherick’s influence clearly in its tactile curves and attenuated legs.

Geoffrey’s Story

Geoffrey Berwind’s memories of his grandparents Nat and Rose feature the music stand in a starring role. After Sunday afternoon lunches filled with laughter and capped with decadent sticky buns, Geoffrey and Rose would play along to her vast collection of classical LPs. With sincerity and passion – if not expertise – Rose played the cello and Geoffrey the viola. Maybe Schubert’s Trout Quintet was on the stereo, or perhaps a slow movement by Beethoven, who “was her God.” Geoffrey recalls that Rose rarely used the music stand but it was a constant presence in the house and deeply cherished.

Largely raised by his grandparents, Rose and Nat’s home was Geoffrey’s safe haven. For him, the music stand became an ongoing symbol of their love and support. “If I’m looking at the music stand,” says Geoffrey, “I’m looking at the people who gave me my life.” The piece has also become an embodiment of some of the core personal values – beauty, friendship, nature, connection – that Geoffrey developed against a backdrop of Esherick works. When Nat and Rose were looking to part with the Esherick works in their home, they were pleasantly surprised by Geoffrey’s desire to give them a second life. The music stand is the last piece that Geoffrey has parted with because it is so personal.

Geoffrey sees WEM as the work’s natural home, and its return as a homecoming to the site where it was made as well as to one of his own “heart homes.” For Geoffrey, the music stand is “so much greater than its label.” It is not just a functional piece of furniture. It’s a lyrical sculpture, an embodiment of grace, a representation of his grandparents, and a teller of tales.