Photograph from Esherick family photo albums of Wharton and Letty under the grape arbor at Sunekrest. Date unknown, likely 1915-1916.

Photograph from Esherick family photo albums of Wharton and Letty under the grape arbor at Sunekrest. Date unknown, likely 1915-1916.

The beginning of Wharton Esherick’s career as a woodworker is typically dated to the time that he, his young wife Letty, and their 3-year-old daughter Mary spent in Fairhope, Alabama in 1919. While in Fairhope – a utopian, experimental single-tax community which was home to Marietta Johnson’s School of Organic Education, and which attracted progressive thinkers and creative people from across the United States – Wharton was given a set of wood carving tools and began carving frames to house the paintings he was otherwise struggling to sell. When the hand carved frames started generating more interest than his reserved, impressionistic paintings, he apparently realized his penchant for wood, which he would spend the rest of his career exploring – and the rest is understood as history. However, the young Esherick family’s visit to Fairhope, while pivotal for Wharton’s work, was spurred on by Letty’s interest in progressive education and creative, alternative lifestyles and communities. After hearing a lecture by Marietta Johnson, it was Letty’s desire to study under her that spurred on the young family’s decision to set sail for Alabama.

Earlier this year, two suitcases were discovered in a closet in the 1956 Workshop building on the campus of the Wharton Esherick Museum. These suitcases were packed full of woven, printed, and embroidered textiles and clothing made by Letty Nofer Esherick. Letty married Wharton Esherick in 1912. The couple separated in 1938, though they never divorced. While Letty has typically been understood as Wharton’s wife and something of a side narrative in the story of his life, she was also an artist and educator with an interesting life and story of her own.

The two suitcases of Letty’s weavings and other textiles that were discovered in a closet of Wharton’s 1956 Workshop, which was home to Ruth and Bob Bascom until last year and is now being used for staff of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

This group of newly-discovered textiles – which include completed and in-process garments, as well as many weaving samples, all of which were likely made between the 1950s and her death in 1975 – complement Letty’s correspondence and other materials in the Wharton Esherick Museum’s archives. They help to flesh out our understanding of Letty and her creative ambitions, bringing to life her story after her separation from Wharton and showing the extent of her skill and drive as a weaver, seamstress, and craftsperson. At the same time, these textiles also offer an opportunity to enrich and expand the way we interpret Wharton Esherick’s life and work, as well as the stories we can tell at the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Matching skirt and halter-top made by Letty Nofer Esherick. Date unknown. Letty likely created these garments from yardage she wove herself.

Aspects of Letty’s story and artistic life from around 1940 onwards are revealed in a number of letters written to Wharton and Mary, which are held in the WEM archives. While Letty maintained the progressive, artistic interests as a young woman and newlywed that brought the Eshericks into contact with people and ideas that had a profound impact on Wharton, Letty’s correspondence reveals creative frustration and mixed emotions about where her attention was being pulled over the course of her marriage. While Wharton was wholeheartedly devoted to his art but was not yet selling much of his work, Letty was not only the primary caretaker of their children but was also doing what she could to support the family financially – primarily growing and selling flowers and taking care of the children of friends and neighbors. As a result, she did not have the time or flexibility to weave as much as she wanted. In a letter to Mary from February 26, 1936, Letty writes,

Got my warp on and now have the job of threading. Am keen to get at it… Get sort of stewed up when I think of all I want to do with my hands and don’t do anything but necessities. And then I think well Wharton is doing it and I guess two in the same house can’t. Am sure glad one of us is…

After her separation from Wharton, however, her perspective and tone shift, as her letters begin to reveal her newfound creative freedom. Letty and Wharton maintained a friendly relationship and a fairly active correspondence even after they were living apart. A letter that Letty wrote to Wharton from Barnegat City (undated, but likely 1947) offers important insight into the creative world and networks which she would explore and embed herself in over the next several years.

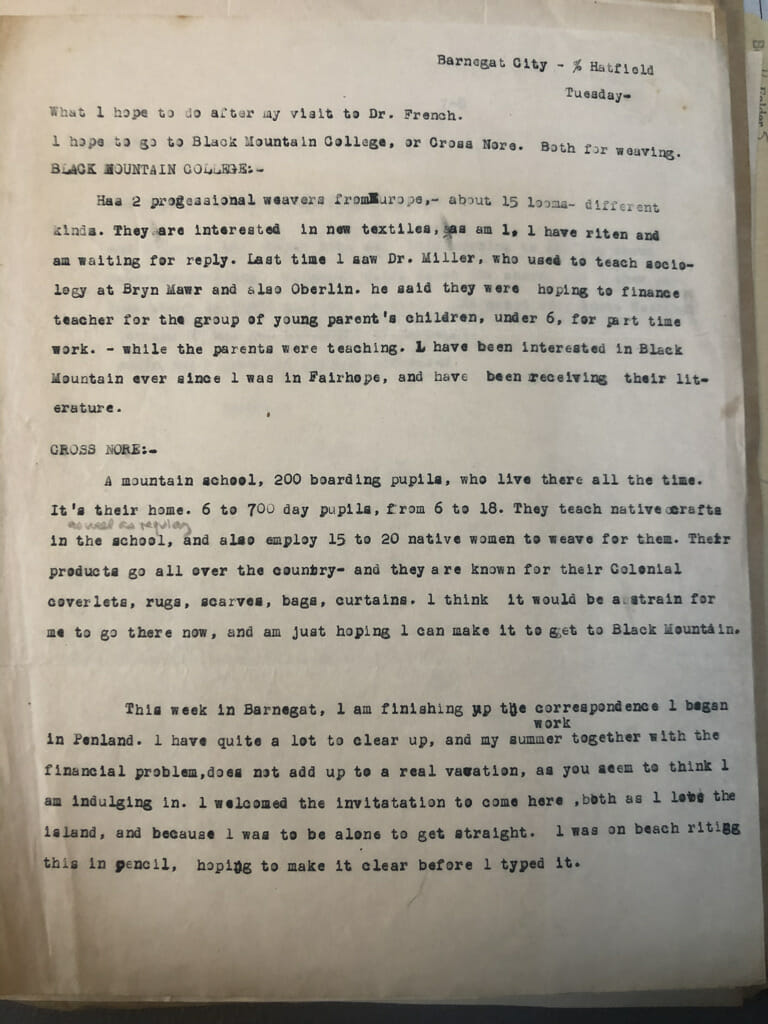

Section of a letter from Letty to Wharton from Barnegat City, possibly in 1947-48.

Section of a letter from Letty to Wharton from Barnegat City, possibly in 1947-48.

Letty mentions a desire to visit Black Mountain College and the Crossnore School, as well as a visit to Penland School of Crafts – all places where she hoped to practice and teach weaving, and each of which had strong weaving programs with reputations in the American craft community at the time. She would end up spending time in the weaving studio at Penland (likely in 1947-1948) and from there would extend her stay in North Carolina by teaching weaving at Crossnore and at Camp Yohnalossee in Blowing Rock. Letty’s presence in the Southern Highlands region of North Carolina during the blossoming of the Appalachian Craft Revival attests to her awareness of and connection to this international hub of craftwork and artistic and social innovation.

Weaving samples by Letty that were found in a manilla envelope with a return address belonging to the Kutztown location of the magazine Handweaver & Craftsman. The sample in the top left closely resembles a pillow on the Bok sofa in Wharton’s bedroom upstairs in the Studio, which is the only known weaving made by Letty that is on display in the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Weaving samples by Letty that were found in a manilla envelope with a return address belonging to the Kutztown location of the magazine Handweaver & Craftsman. The sample in the top left closely resembles a pillow on the Bok sofa in Wharton’s bedroom upstairs in the Studio, which is the only known weaving made by Letty that is on display in the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Additionally, correspondence from late 1948 also reveals Letty residing at Letchworth Village in Thiells, New York – a residential institution for physically and mentally disabled children and adults – where she taught weaving as part of the institute’s occupational therapy program. By the mid-1950s, it seems that Letty was mostly settled back in Pennsylvania, teaching weaving and doing weaving demonstrations at the Fort Hunter Museum in Harrisburg though in letters to Wharton from 1956 she also mentions traveling to Mexico to attend a craft school outside of Mexico City.

Clipping from December 14, 1952, issue of the Sunday Patriot-News showing Letty giving a demonstration on one of the looms at the Fort Hunter Museum in Harrisburg, PA.

Clipping from December 14, 1952, issue of the Sunday Patriot-News showing Letty giving a demonstration on one of the looms at the Fort Hunter Museum in Harrisburg, PA.

These materials in the archives at the Wharton Esherick Museum show Letty exploring and pursuing a life as a weaver and educator in a number of progressive communities and institutions throughout the decades after her marital separation and her recovery from encephalitis. Throughout this period, Letty discusses in her letters a desire to devote herself to weaving, and to find ways of supporting herself through her craft. While we know that she continued to struggle financially, it is clear that she was active and traveling widely, interacting with communities of artists, and exploring a world of relative creative freedom. While there is still much to be discovered about Letty and her experience pursuing a career as a professional weaver, her story clearly continued and remained interesting and full of exploration after her separation from Wharton.

Chain stitch embroidery on a linen tunic found in one of the suitcases. Embroidery and garment sewn by Letty, though the linen textile that the tunic is made from is likely store-bought.

Chain stitch embroidery on a linen tunic found in one of the suitcases. Embroidery and garment sewn by Letty, though the linen textile that the tunic is made from is likely store-bought.

The newly discovered weavings at the Wharton Esherick Museum – paired with Letty’s correspondence and placed within the context of her life and the networks and communities of artists and craftspeople in which she embedded herself – offer an entry point into an under-appreciated aspect of the Esherick story. While the Wharton Esherick Museum exists to highlight and celebrate the life, work, and legacy of Wharton Esherick, Wharton himself lived and worked in a manner that may have looked quite different were it not for Letty and her own interests and ambitions. These materials help us to better understand Letty, who lived in Sunekrest for many years and was, for a time, a crucial part of Wharton’s life and yet has not received the attention she deserves. At the same time, they also assist us in expanding the scope of the stories we can tell at the WEM, offering insight that allows us to position Letty as an important influence on Wharton, and slightly reframing the trajectory of his career as the “dean of American craftsmen.” Finally, they offer an opportunity to consider Letty within the broader landscape defined by female craftspeople around mid-century, allowing us to better understand when and how women experienced and accessed professional creative lives at this moment in time.

Blog post by Jena Gilbert Merrill, Curatorial & Interpretation Intern at the Wharton Esherick Museum and MA candidate in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware.

May 2022