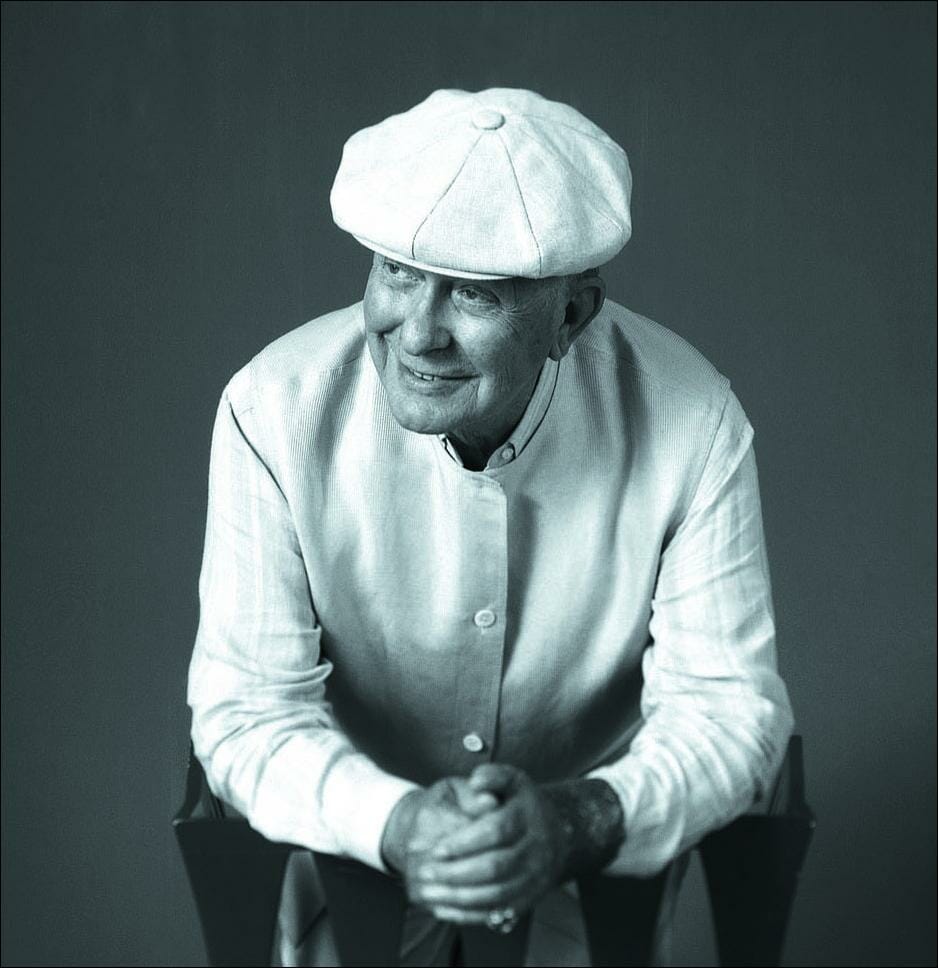

Photo by Paul Godwin

Last December we received the sad news that the internationally celebrated craft and textile icon Jack Lenor Larsen had passed at the age of 93. A giant in the field of craft, we have been thinking back on the legacy Larsen leaves behind as a creator, a collector of work by many including Esherick, and as a personal friend to Esherick and the Museum.

Born in Seattle, Larsen first pursued a degree in architecture at the University of Washington but was ultimately drawn to textiles and hand-weaving. At the encouragement of Cranbrook Academy of Art Alumnus Ed Rossbach, Larsen pursued an MFA in Fiber at Cranbrook, studying under the weaver Marianne Strengell. After graduating in 1951, he declined academic offers in favor of launching his own company and before long was at the forefront of textile design in America. Larsen grew to be a premier name in the field and was honored with numerous exhibitions and awards. His works can be found in major museum collections around the world. The New York Times wrote a wonderful tribute to his accomplishments which you can read here.

LongHouse Reserve, Larsen’s 16-acre reserve and sculpture garden located in East Hampton, New York includes outdoor sculptures by Yoko Ono, Buckminster Fuller, and Willem de Kooning, among others. Image courtesy of LongHouse Reserve.

Larsen produced both hand- and machine-woven textiles with global influences that were at once innovative and tied to tradition. He drew inspiration from both an admiration of historically-grounded craft forms and the latest technologies. Many of Larsen’s designs were created for a large-scale market — among his clients were Pan American and Braniff airlines – but his textiles for interiors can be found in conversation with iconic architecture like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and Louis Kahn’s First Unitarian Church in Rochester, New York. One of Larsen’s best-known fabrics, Magnum, was designed for the theatre curtain at the Phoenix Opera House and blended inspiration from Indian textiles with an unusual material: mylar.

At the start of PBS’s Craft in America: “Visionaries” episode, Jack Lenor Larsen’s voice is heard musing, “Convention is such a waste of time. If someone has already done it, why do that?” Larsen’s boundless curiosity and innovative drive – traits he certainly shared with Esherick — did not end at the edge of his own creative making. He was a supporter and champion of craft in myriad ways: as a teacher and thought leader, author of numerous books, collector, and curator. In 1992, Larsen established LongHouse Reserve at his home on Long Island. A public sculpture garden and home to his expansive collection of craft objects, the grounds exemplify Larsen’s drive to bring influences from beyond the world of textiles into the medium and, conversely, to incorporate the sensibilities found in textiles back into the garden and world around him.

The 2011 exhibition Wharton Esherick in LongHouse Collections curated by Jack Lenor Larsen included the 1940 World’s Fair Dining table and Chairs, and the archway from the Curtis Bok House seen here. LongHouse Reserve Collection, gift of Jack Lenor Larsen. Image courtesy of LongHouse Reserve.

Each visionaries in their respective mediums, Larsen and Esherick came to know each other in the 1950s, as the efforts to connect and celebrate the world of craft grew nationwide (thanks in large part to the efforts of patrons like Aileen Osborn Webb and the formation of the American Craft Council). When the opportunity arose Larsen began acquiring Esherick’s work. After Esherick’s death in 1970, Larsen continued to be a friend to the Museum, lending advice and support as a member of our advisory board.

Larsen was an avid collector of Esherick’s work, and his collections at LongHouse include a number of important Esherick pieces including both tables and multiple chairs featured in Esherick’s Pennsylvania Hill House exhibition at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair and an arch from the Curtis Bok house. The Bok House was Esherick’s largest commission, beginning in 1935, and an important early opportunity for him to explore Expressionist designs in a built environment. Other celebrated architectural elements, like the Fireplace and Doorway, and the Staircase, are also now in museum collections. The five-sided World’s Fair Table, was made in 1939, just after the Bok House project was completed. In it we can see a pinnacle moment of transition as Esherick moves from his Expressionist explorations to the organic forms of his work in the 50s and 60s. Also in the Longhouse collection is a painted bench, library ladder, music stand, and cubist mirror.

Jack Lenor Larsen and WEM Co-Founder Bob Bascom at the 2011 Annual Members’ Party.

These pieces, alongside loans from the Wharton Esherick Museum collection were included in an exhibition of Esherick’s work at Longhouse in 2011. Images from the exhibition, along with a statement by artist Martin Puryear, can be found on the Longhouse Reserve website. That same year we were honored to host Larsen as the guest speaker at our Annual Party, an event we hold every September as a celebration of Esherick and our community and which we are so grateful to say Larsen was a part of. We encourage you to explore more about Jack Lenor Larsen and his legacy at LongHouse Reserve and through his oral histories at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

Be sure to watch PBS’s Craft in America: “Visionaries” episode which features Larsen and highlights a few Esherick works in his collection.

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

February 2021