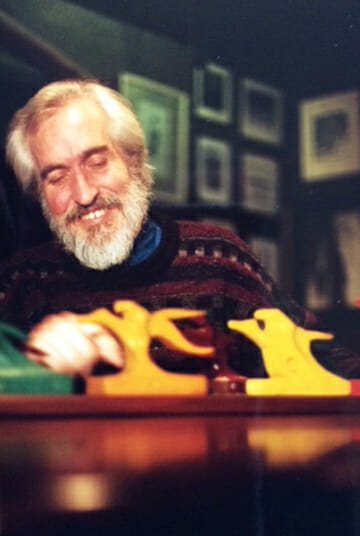

Rob Leonard admiring Esherick’s sense of play in ‘The Race,’ the horse and jockey game Esherick carved for his children. Photo by Lori Lighton.

I came to the Wharton Esherick Museum along the same path as most of our visitors. In the late ‘70s, the early years of the Museum, I would occasionally come across a brochure for the Museum. Intrigued, I put the brochure in my pile of “things I would like to do someday.” My first sense from a terse review was that this seemed to be the interesting home of some eccentric farmer and was worthy of a visit.

My initial visit to the Studio took place in December of 1989 in the form of an interview for the position of Museum Director. My interview began with an extensive tour of the Studio, presented by Mansfield ‘Bob’ Bascom, Esherick’s son-in-law and volunteer Museum Director. I absorbed every word of that tour, assuming that if I took the position I’d better know what this was all about. The tour was followed by an interview with Bob, Ruth Esherick Bascom and Board Member, Paul Modes. We talked for about two hours and I picked up on the passion invested in this seeming “Mom and Pop” operation. I came to understand the unwavering commitment with which Bob, Ruth and many others stewarded Esherick’s legacy, driven by the belief that the Studio must be preserved and shared with the public.

Nearly twenty years into their stewardship, Bob and Ruth were seeking someone who could apply full-time effort into running and promoting the Museum, with a focus on raising major endowment funds to enable the Museum to be more self-sufficient. I was immediately taken by the uniqueness of the place and felt the cause was a worthy one. I expressed my interest and we agreed – upon Board approval – to try each other for a year.

I started this adventure on January 1, 1990, just after a rare “Blue Moon” on New Year’s Eve. I determined that I needed to spend at least the first three months learning all I could about Wharton Esherick, the Museum’s history and operations, and the museum community before making any decisions on how to proceed. In those early days, I became concerned that the remoteness of the Studio and the difficulty in being able to tell such a complex story in a simple marketing format was a significant challenge. What I didn’t immediately realize was the passion of the community which surrounded the Museum – the family, volunteer board and docents. It was the dedication of our community, rallied around the warmth and ingenuity of Esherick’s legacy embodied in the Studio, that made our success possible.

Rob Leonard in his new role as Executive Director of the Museum. Photo from 1990, originally featured in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

It became evident each time I spoke with any of them and my enthusiasm increased. And It became clear just how transformative a trip to Esherick’s Studio was for so many of our guests. One experience, very early on, made me realize what a significant endeavor stewarding this place really was. The Studio is closed to visits during January and February but I would do impromptu tours if possible. That first January, a local person called and asked if they could bring a visitor over and I obliged them. As the tour finished, I asked them to please sign our guest book. (We did not have the visitors’ center yet; all our few sales items were placed on the dining room table.) After the people left, I looked at the guest book and discovered that our visitor was from East Germany! Just weeks after the Berlin Wall came down, this person sought out the Esherick Studio. That moment became the impetus for my determination that this place must be sustained and promoted – it needs to be here for future generations.

In the twenty years that I served as Executive Director – and the past ten years as a docent – that belief has been reinforced hundreds of times. The responses of visitors have made that clear:

The woman who broke into a massive grin upon seeing the dining room floor, the opera singer who likened the tour to “walking through a violin,” and the pottery craftswoman who almost fainted in the Studio – overwhelmed by “all this creativity.”

The craftsman who was juried into two of our annual woodworking competitions, winning an award the second time. At the Members’ Party show opening his parents told me they brought him to the Museum as a teenager and he remarked, “This is what I want to do.”

The man who seemed relatively passive – almost bored – during a tour. As he was leaving the building, he shook my hand and said, “This is the most remarkable experience I’ve had in a long time!” Looking into his eyes, I am certain that he made some significant life change as a result.

There are many such experiences that each of the Museum’s docents could share. The impact on visitors is clear. Esherick, by living true to himself, created a space where we can all share in the richness of our human connections, our aspirations and trials, our ingenuity and spirit. Esherick’s life and story, culminating in his Studio, truly touches lives and is vital in all senses of the word. It has been my joy and privilege to be a part of it, and to help it live on.

There are many such experiences that each of the Museum’s docents could share. The impact on visitors is clear. Esherick, by living true to himself, created a space where we can all share in the richness of our human connections, our aspirations and trials, our ingenuity and spirit. Esherick’s life and story, culminating in his Studio, truly touches lives and is vital in all senses of the word. It has been my joy and privilege to be a part of it, and to help it live on.

Post written by former Executive Director, Rob Leonard.

April 2020

As a donor-dependent organization, we’re deeply grateful for the ongoing support and dedication of our Museum family. Learn more about how you can support the Studio.