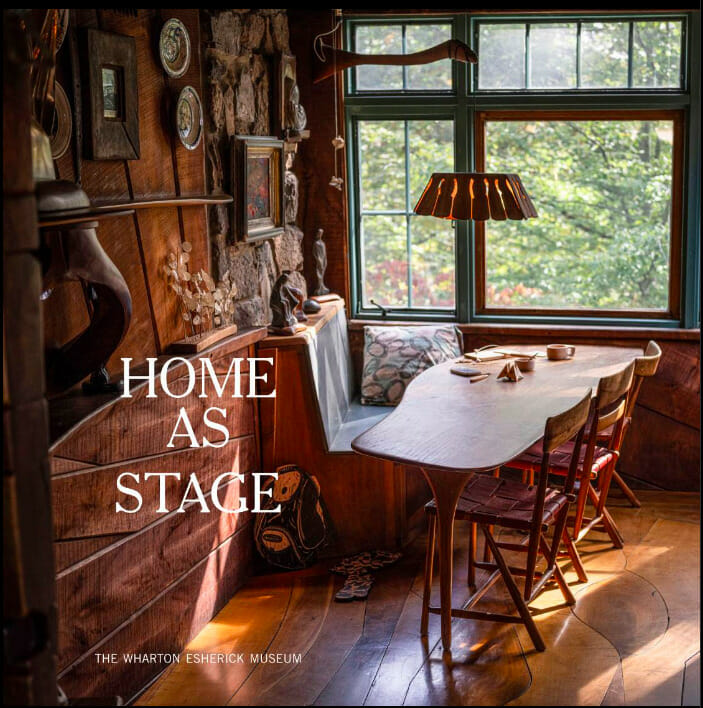

Home as Stage

September 15, 2022 – December 30, 2022

2022 marks the 50th Anniversary of the Wharton Esherick Museum, which opened to the public in the fall of 1972. Throughout this year, a series of installations and programs have explored the idea of “home” in order to celebrate WEM’s 50 year history and envision the next fifty years and beyond. Home as Stage is the final installment in this series. It asks visitors to consider Esherick’s home and Studio not only as the set on which the artist’s ambitions played out, but also as a stage that hosted players – often other artists – whose conversation, collaboration, and connection made Esherick’s life that much richer and more profound.

To honor that legacy and create new opportunities, WEM invited four Philadelphia-based contemporary artists – Emily Carris-Duncan, Kay Healy, Colin Pezzano, and Stacey Lee Webber – to use the space as a stage for their own creative practices exploring the world of objects through skilled engagement with wood, metal, and fiber. For this project, Carris-Duncan, Healy, Pezzano, and Weber spent time in the Studio and its archives, developing connections with aspects of Esherick’s life, the players in his story, and the physical nature of this place. The works selected for display in Esherick’s space exist as both material demonstrations of that connection across time as well as discreet works of art imbued with each artist’s distinctive voice and vision. In the text below you’ll find more about these four practitioners, often in their own words, about their backgrounds, outlooks, and how they were inspired by the opportunity to stage a work at WEM.

The contemporary artworks on view are complemented by a selection of textile objects on loan to WEM from the Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM). Produced by four artists and architects of Esherick’s era with compelling connections to the artist’s life, career, and experiences – Viola Frey, Toshiko Takaezu, Lenore Tawney, Robert Venturi – their placement in Esherick’s Studio explores ideas around the artist’s networks and connections on an intimate, inviting stage. Furthermore, the story of the FWM as a space that invites creatives who may not work with textiles to push beyond the assumed boundaries of their practice is one that resonates with Esherick’s own interdisciplinary approach to art making and collaboration.

Meet the Artists

Emily Carris-Duncan

I first encountered Esherick’s work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I stumbled on his Fireplace and Doorway from the Bok House, from 1938. I didn’t know much about him, but I loved the way his work was alive in the room. He imbued these mainstay objects with elegance and a playful personality in the asymmetrical symmetry of his carvings and copper work. My work as a textile artist has made me notice the way lines intersect and play off each other. The corners of Esherick’s Fireplace evoke traditional quilt patterns like the log cabin or house tops. It also brings to mind some of the improvisational quilt work by the Gee’s Bend Quilt Collective. I became fascinated with the work. I would find myself visiting it whenever I was in the building and raving to friends about how good the honey oak wood was to look at. When I got the invitation for this project, I jumped at the chance to participate.

My work for this exhibition was inspired by the links I found between Esherick work and textile design. I’ve found that Esherick’s woodwork is in an interesting conversation with textiles, sharing similar design elements as traditional and indigenous textiles. He appears to be heavily influenced by the textile world because of his association with his wife Letty. He employed the use of upholstery and weaving in his furniture and started his woodworking life while at the Marietta Johnson’s School for Organic Education, where the textiles were core to the institution’s teachings. Additionally, the African American quilt tradition that my work is rooted in sees improvisation as the ultimate form of expressive freedom. Esherick’s work is very much in the same vein. He responds to his materials, allowing them to reveal themselves at his hand. His practice is his own; it is in a dance with his collaborators like Letty Esherick, June Groff, and Ed Ray which informs the philosophical flow of the work.

I used all of these elements when crafting my piece. I wanted my quilt to embody Esherick’s work and relationships. I cross referenced the wood in his work with what was dyeable, and used woods from the Esherick campus to dye the quilt on view in the Studio. Having the opportunity to visit the studio and learn about Esherick, Letty, and their community taught me about the beauty of surrendering to the artist’s life. If you want a beautiful life, you have to craft it. Esherick left behind a beautifully expressed life that continues to impact the public’s fundamental understanding of art and nature.

Emily Carris-Duncan is an artist and educator. Her/Their work explores the materiality of trauma using textile techniques. Carris links the personal and cultural legacy of slavery while mulling the question of how trauma lives on after the act. They have recently exhibited at The Colored Girls Museum and Past Present Projects in Philadelphia, as well as EFA Project Space in New York. They were a 2020 fellow at The Center For Experimental Ethnography at the University of Pennsylvania and a 2021 Smithsonian African American Craft Summit participant. They currently live and work in Vermont and Philadelphia.

Kay Healy

I have visited the Wharton Esherick Museum several times and have always enjoyed the immersive experience of walking through this handcrafted space. Esherick turned mundane objects and spatial functions, like a chair or utensil drawer, into artistic experiences. I am similarly interested in mundane, everyday objects that tell a story about the owner or maker.

As I was walking through the Studio in preparation for this project, I felt strongly that I did not want to interfere too much with the environment. I like when my work is incorporated into the existing layout and the pieces are able to be discovered. I wanted to have a “soft touch” approach to installing the work so it is embedded seamlessly within the space, hopefully to surprise and delight viewers, and not be obtrusive to viewing Esherick’s work.

I was interested in learning more about Esherick’s wife Letty, because I often find that creators of spaces like this have other people that have done invisible labor. During the visit for this exhibition, I learned that Esherick’s partner since the 1940s, Miriam Phillips, lived on the site for 15 years after Esherick’s passing and even led the tours in the early days of the nonprofit. For this reason I created two toothbrushes to represent their cohabitation in the Studio. I had previously thought of the space as a lone artists’ abode, since only his clothing and personal objects are shown.

Through her life-sized drawn, painted, and screen-printed fabric installations, Kay Healy investigates themes of home, loss, displacement, and resilience with interview-based projects. Healy received a BA from Oberlin College, and a MFA from the University of the Arts. Her installation Coming Home was purchased by the Pennsylvania Convention Center, and her work was supported by the Independence Foundation’s Fellowship in the Arts. Healy has had solo exhibitions at Gallery Madison Park in New York City, Gallery Septima in Tokyo, Japan, the Windgate Gallery in Fort Smith, Arkansas, the Delaware Center for Contemporary Arts, and the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts and other galleries.

Colin Pezzano

In my home, I find I am often expanding out of the studio into other corners of the house, carving on the porch, drawing in bed, or painting at the table. In a cluttered stage setting that inhabits the dining room area of the museum, I expose aspects of process normally unseen. A disorganized pile of objects and material scattered across the dining room table. Utilizing several different techniques, I replicate a selection of objects in wood. The trompe l’oeil objects mimic tools important to my own practice. In these small favors, I connect the raw material directly to the process. This scene is charged by the studio it inhabits. The dining room becomes both a physical realm and symbol where Esherick and I occupy the same space.

Through craft, we connect our actions and memories to the traditions of woodworking, and contribute to its continued conversation. In the dialogue, I add my own perspectives and experiences to the medium. Through the objects and tools, we are able to communicate with the past, present, and future. Connections through cultural tradition are created and solidified through spaces and objects we all interact with. In an accumulation of objects and tools, the vision becomes clearer.

Accumulated Objects, 2022

Poplar, basswood, heart pine, maple, plywood, walnut, white oak, cane, acrylic paint, felt

Collection of the Artist

Colin Pezzano is a woodworker and craft artist based in South Philadelphia. His practice is defined by utilizing digital and hand processes to pass along humor, pathos, and memory into his chosen materials. Colin graduated from University of the Arts in 2014 with a BFA in Crafts and shortly after received the Windgate Fellowship Award. In 2022, he received the Windgate-Lamar Fellowship Award, given to awardees who have continued to evolve their practice post graduation. Colin has had two solo shows, “Contain You” and “Still Life With Dead Game” at Bridgette Mayer Gallery and the Allens Lane Art Center, respectively. His most recent project is a series of site-specific installations which will be presented around Philadelphia which will coincide with the release of Colin’s book Soma, a graphic novel in woodcuts. During his career Pezzano has participated in group shows and juried exhibitions, and attended residencies in the USA and Sweden. He maintains his practice in his basement studio.

Stacey Lee Webber

When I was invited to do this project, I was loosely familiar with Wharton Esherick – mostly his furniture in museum collections and in Helen Drutt’s collection. The exhibition scouting tour was my first time on the property, and I am now enamored with his creativity and lifestyle. I am a full time artist and can relate to that aspect of his life, but the oasis that he built is much more tucked away. It definitely gave me ideas about how my factory live-in studio could transition into a woodlands studio one day. The city chaos is exciting and keeps me on my toes, but there are times when I long for many quiet days… although thinking about the endless projects Esherick must have taken on to make his home and studio functional is daunting!

The penny Chainsaw on view at WEM continues the penny tool series I started in 2008 to question the value of labor: what is one’s hand-work worth? As this series has continued, the tools have become more aggressive and more complex. I started making basic hand tools, such as a hammer and screwdrivers, and now make more aggressive tools such as circular saws and, most recently, this chainsaw. As a contemporary metalsmith, I cherish working with found materials whose history is physically evident. I strive to make artwork that interests a broad range of viewers and challenges their preconceived notions of the objects that surround them.

Envisioning the penny Chainsaw on Esherick’s Flat Top Desk was exciting! First, what struck me was the warmth of the copper penny sculpture and the warmth of his wood furniture and sculpture, along with the beams of daylight in his space. The chainsaw fits in his studio, which was once his primary workspace, surrounded by the forest. During my tour, men were in trees working on cutting down tree limbs as we discussed the chainsaw vision and it seemed very appropriate. This chainsaw has been a huge undertaking for me. I am often working on commissions or smaller pieces to make a living. The chainsaw has been a passion project that started four years ago. It was an undertaking that I was not sure I could accomplish technically and find the time for financially. I loved the idea of an aggressive penny tool that is masculine and life threatening. I am thrilled to have figured out how to make the sculpture – and more thrilled that I have found the time to make it and to have WEM’s incredible space in which to show!

Stacey Lee Webber received her BFA from Ball State University and an MFA at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. In 2011, Webber moved to Philadelphia to pursue her dream of being a full time artist. After four bustling years teaching at Tyler School of Art, the University of the Arts, and Rowan University while also working as a production jeweler, she made her dream come to fruition in 2015. Webber is currently working and living on the northeast side of Philadelphia, where she has made a career of making and selling artwork and jewelry. Webber has exhibited her work around the world including the Cheongju International Craft Biennale in the Republic of Korea, Gallery Okariya in Tokyo, and Sophie Lachaert Gallery in Belgium. Her work has been curated into the permanent collections of The Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington DC, the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton Massachusetts, the fine art collection of Wells Fargo Bank, the Kamm Teapot Foundation collection, and numerous private art collections around the world.

Selections from The Fabric Workshop and Museum

The loan of these objects from the Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM) demonstrates just some of the ways that other artists in the contemporary art, craft, and architecture spheres are connected to Esherick’s life and work. Notably, each of these artists belong to the generation after Esherick, who was born in 1887, and are linked to Esherick during his latter decades, when he was both prolific and seen as an elder statesman of the expanding Studio Craft movement by other artists. Esherick’s place in the creative ecosystems of his time is strengthened when we shine light onto the stories of these connections, whether intimate, professional, or somewhere in between. WEM is excited to have the opportunity to partner with FWM to place domestic-scaled works by Frey, Takaezu, Tawney, and Venturi within Esherick’s Studio to approach these conversations in new ways.

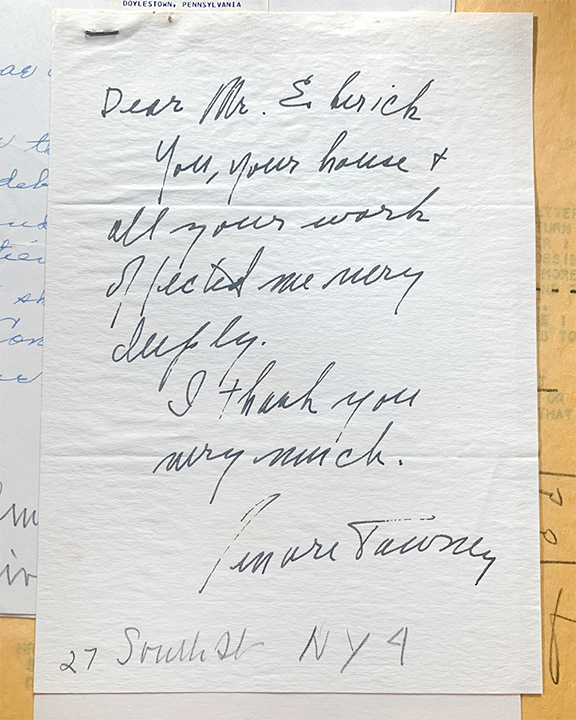

Letter to Esherick from Lenore Tawney.

Venturi is often considered the father of Postmodern architecture. His motto “less is a bore” riffs off the famous Modernist dictum, and in turn, seems in keeping with the proliferation of artwork and ephemera in Esherick’s home and studio. For many years, Venturi, along with his partner and wife architect Denise Scott Brown, resided in the Chestnut Hill home previously belonging to Helene Fischer. Fischer, head of the Schutte-Koenig Company, was one of Esherick’s most important patrons beginning in the late 1920s and commissioned some of his best known works. The home that she and Venturi both resided in was depicted by Esherick in his well-known print The Lane (1931). This is not Venturi’s only Esherick connection, however. Venturi worked for the architect Louis I. Kahn – Esherick’s collaborator in creating his purpose-built workshop – between 1956, when the workshop was finally realized, and 1958.

Just as Esherick pushed at the boundaries of furniture, Tawney, Takaezu, and Frey expanded those of fiber and ceramics. As documents from WEM’s archives demonstrate, Tawney visited Esherick’s studio on January 18, 1961 and was deeply impacted by her time here. The purchases she made during that visit, including the bowl and three of the stools mentioned in an invoice, were later gifted to the collection of the John Michael Kohler Art Center as a part of Tawney’s larger estate. Esherick shared many important stages and networks with Tawney, Takaezu, and Frey, including leadership roles at the first conference of the American Craft Council at Asilomar; exhibitions such as The Brussels World’s Fair (1958), The American Craftsman (1964), and Collector: Object/Environment (1965); and colleagues like Henry Varnum Poor, a close personal friend of both Esherick and Takaezu. Frey’s print from her FWM collaboration is titled Artist’s Mind/Studio/World, perhaps an ideal summation of what a visit to WEM truly feels like.

All artwork produced in collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia.

Courtesy of the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia.

Home as Stage Catalog

This catalog to accompanies the exhibition “Home as Stage,” the final exhibition in a series of three installations exploring ideas of “home” in celebrations of the museum’s 50th anniversary.

Featuring the work of four Philadelphia-based contemporary artists – Emily Carris-Duncan, Kay Healy, Colin Pezzano, and Stacey Lee Webber – complemented by a selection of textile objects on loan to WEM from The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Home as Stage asked visitors to consider Esherick’s home and Studio not only as the set on which the artist’s ambitions played out, but also as a stage that hosted players – often other artists – whose conversation, collaboration, and connection made Esherick’s life that much richer and more profound.

You can purchase a 24 page softcover copy or view it free online!