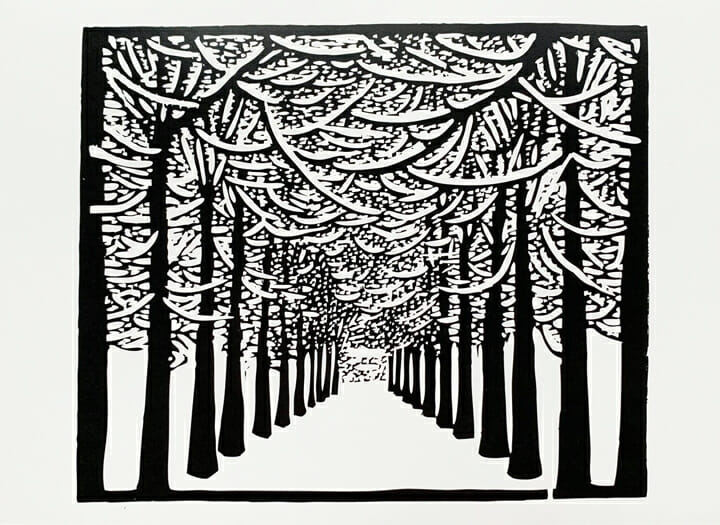

A tree-lined drive, simple and clean in it’s balanced symmetry creates the scene of Wharton Esherick’s woodcut print The Lane. This print is a favorite among guests to the Wharton Esherick Museum, and it’s easy to see why. The frontal composition is a welcome, open invitation into the scene, with the rhythm of tree trunks and the graceful swoops of snow-covered branches above leading your eye into the distance. We issued The Lane as a notecard in our museum store this year (chosen by popular vote on our Facebook page!) and to celebrate we’d like to share some deeper insights into this celebrated woodcut.

There are a few figures that come up again and again in Esherick’s story, and one of them, Helene Koerting Fischer, lived with her husband at the end of the tree-lined drive depicted in The Lane. Fischer was one of Esherick’s greatest patrons. She supported his work through several commissions, first for her home in the Chestnut Hill neighborhood of Philadelphia and later for the office of her company, Schutte-Koerting.

Helene Fischer’s first purchase of Esherick’s work was a 1929 sculpture of a reclining dancer, Finale, which she saw on display at the Hedgerow Theatre. Esherick, who was very close with Hedgerow Theatre’s founder, Jasper Deeter, often displayed work there in the 1920’s and 30’s in hopes of finding buyers for his work. In the case of Helene Fischer, he found a true believer in his talents. Before long she commisioned Esherick to design a pedestal for the sculpture, which quickly evolved into an expressionist-style Victrola cabinet. Fischer had a particular passion for expressionist work and among her many commissions are some of Esherick’s most celebrated designs in this period, including the Fischer Corner Desk and Fischer Hall Bench.

Helene Fischer served as the President of the Schutte-Koerting Company in Philadelphia for several years, which designed and manufactured precision machine parts. She proved to be a determined and confident leader for the company, after which she was elected Chairman of the Board of Directors. While in charge of Schutte-Koerting, Fischer commissioned Esherick to design a new boardroom that would embody the dynamic nature of the company under her leadership. The set included a desk, chair, and wastebasket for Fischer, as well as a board table with several chairs, and a door, radiator cover and overhead light for the room.

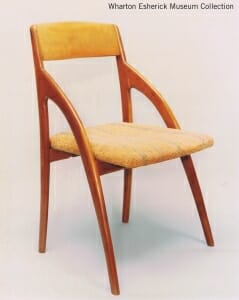

The SK Chairs Esherick designed for this boardroom set (so named for the Schutte-Koerting company) were groundbreaking, introducing a new form of chair construction. The front legs arch gracefully to meet the back of the chair well above the seat for this design, a style that future furniture makers continue to adapt and explore. When the company sold in 1971, Helene Fischer gave the boardroom furnishings to the Philadelphia Museum of Art which used them in their own boardroom for several years.

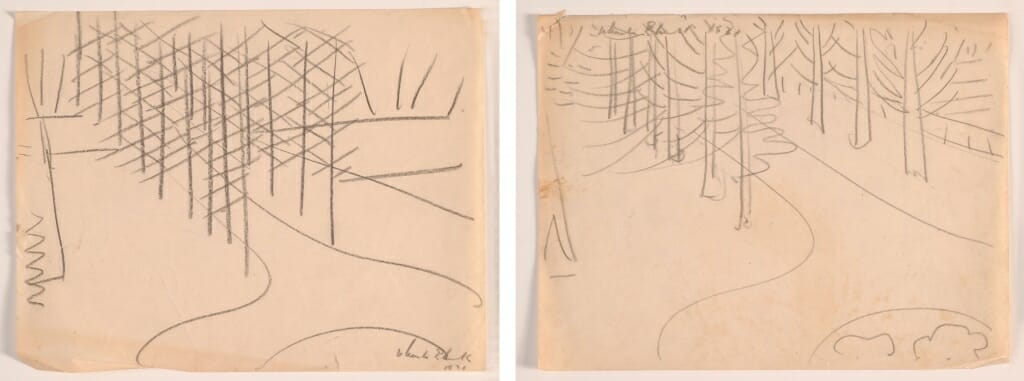

As was common for Esherick, the client relationship was a friendship as well, and Helene (or ‘Ma Fischer’ as he often called her) was one that he visited often. Perhaps The Lane‘s success is due in part to Wharton knowing the subject well and drawing it many times beforehand on these visits. Drawings by Esherick from 1931 seem to show the view from the house. The turn-around, which is in front of the actual house, is seen in the bottom right of both sketches. It’s likely that Wharton spent a good deal of time visiting with the Fischers, perhaps even staying in a guest bedroom with such a view. Through the photos and drawings, we can see the inspiration for The Lane and appreciate the choices Esherick made to achieve the stylized effectiveness of the print.

This painting on paper by Wharton depicts a baker and a carpenter (Helene and Wharton) among the trees of the lane again. Text along the top reads “A carpenter and baker enters on New Year’s Eve 1931”. Private Collection. Photo courtesy of Mark Sfirri.

It would be hard to overstate the importance of Helene Fischer as an early supporter of Wharton Esherick’s work, providing much-needed income, but also enthusiasm and vision for what his work could be. She was even instrumental in connecting him with the Bavarian sculptor, Hannah Weil, which afforded him the chance see first hand the work of the German Expressionists. Esherick himself gifted Fischer small pieces and sculptures over time, tokens of friendship that show his appreciation for the opportunities she had provided him. In this way, it’s fitting that her home and drive (which would later be owned by the architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown) be captured and immortalized in this beautiful print.

Thank you to Mark Sfirri for sharing his research and resources for this article. Sfirri has written several articles on Esherick’s work including “Anatomy of a Masterpiece” for Woodwork Magazine, which discusses in depth the Fischer Corner Desk.

More on Wharton Esherick’s commissions for Helene Fischer can also be found in “Wharton Esherick: Journey of a Creative Mind” by Mansfield Bascom.

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.