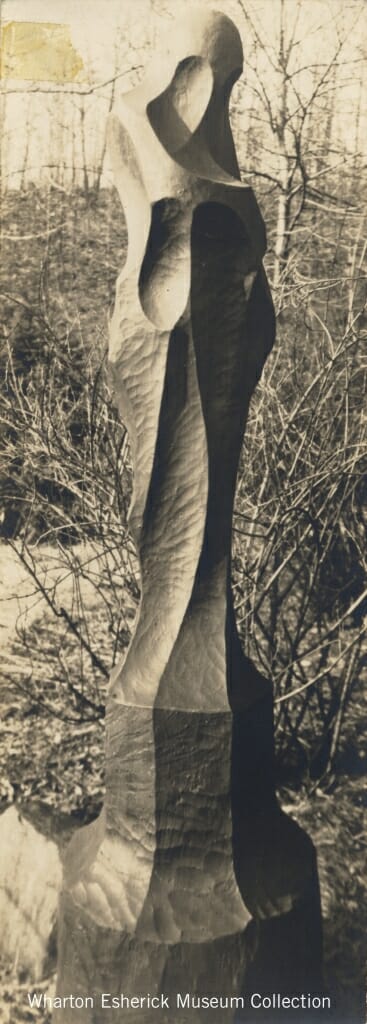

The captivating and sorrowful sculpture, Nocturne, made by Esherick in 1927 memorializing Letty’s heartbreak at the loss of their infant daughter.

Light plays an integral part in the experience of sculpture, as light cast over a form is what reveals a sculpture’s dimensionality. Of course, at the Wharton Esherick Museum visitors are invited to reach out and feel the curves and angles of our surroundings, but we can see also how Esherick used the visual impact of lighting to accentuate his sculptures, built-ins, and architectural elements. Esherick famously incorporated lights into the literal form and function of some pieces, though the effect of light over the angles and concave curves of a sculpture like Nocturne as it seems to sorrowfully turn away from our view is equally essential to the success of the artwork.

Esherick’s use of light has ranged significantly throughout his career, as his approaches drew anywhere from the dramatic to the pragmatic. Among the earliest examples of Esherick’s lighting design in our collection are a set of Expressionist style lamps. In Table Lamps, from 1931 and 1932, the bulb is nested at the base of the form with four spires surrounding it, combining the starkness of bare-bulb light shaded only by the wood spires.

Many of Esherick’s earlier explorations in lighting borrow from the vocabulary of theatre sets and German Expressionist films – highly dramatic and at times downright spooky. He was a fan of theatre, taking in plays regularly at the Hedgerow and even designing a few sets at Hedgerow around 1930. Esherick’s appreciation for the 1920 German Expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is well-known, and seminal works of his like the Curtis Bok House fireplace and doorway from 1935 seem to exemplify the heightened theatricality in his furnishings. The doorway came first, inspired by the drapery of fabric, but through a “prismatic” lens – a motif he continued in the fireplace that followed. The repeated accordion-like angles on the fireplace and door create a vivid series of alternating light and shadow stripes. One can just imagine these exaggerated angles flickering and dancing around a crackling fire. Esherick also added recessed lighting in the fireplace mantel to illuminate objects from below – which any kid with a flashlight knows is the most unnerving option!

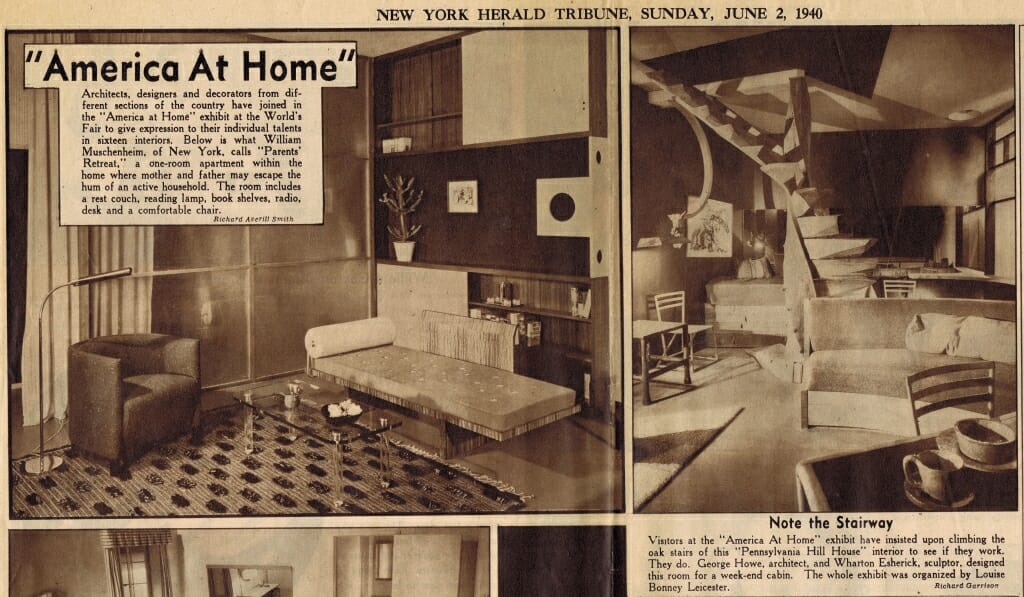

A look at the Pennsylvania Hill House exhibit from 1940, Esherick’s contribution to the New York World’s Fair thanks to an invitation from George Howe, reveals a strikingly unique approach to lighting in an interior domestic space. Compared with others on display Esherick’s space was complex and active. One can imagine moving through the space – over, under, behind, around, obscured, spotlit – with the depth of light and shadow playing an enhancing role to the sculptural surroundings.

Wharton Esherick’s comparably active and angular space, “A Pennsylvania Hill House” at the New York World’s Fair in 1940.

Esherick is also celebrated for integrating lighting directly into his sculptural furniture. Among the earliest examples of this is his Walnut Burl End Table with Lap Light from 1932, which incorporates a lamp specifically intended for needlework projects. Esherick continued exploring the potential of built-in lighting in the Fischer Hall Bench (1938), which has a series of drawers underneath the seating intended for record storage. Each drawer was equipped with recessed tube lights, which automatically turned on for easy reading. Esherick added this handy feature to many future drawers and cabinets, including those in his own home like the 1958 Cabinet Desk. This integrated lighting is brilliantly pragmatic but also has a theatricality to it. Any guest invited to operate the Cabinet Desk could tell you the delightful moment of magic he has introduced to the act of operating the furniture, heightening the joy and discovery of the piece.

For those lights throughout Esherick’s Studio not housed within a certain piece of furniture, they all serve to enhance the warmth and intimacy of the space. Using many peripheral lights over a central “chandelier”, the lighting draws you into the Studio’s various nooks and crannies, like the telephone “desk” under the stairs, or the three-shelved Expressionist style bookcase at the top of the spiral steps. Several swinging lights in the Studio, with arms that reached out over desks and tables allowed Esherick to position them as needed. Walnut slats make up the shades for these swinging lights, while other bulbs in the Studio are shaded in even more unexpected ways. Paper, rawhide, a wooden board, even a pot lid, are all used by Esherick to defuse and direct light. These quick solutions to a bare bulb seem to embody Esherick’s unconventional approach to his Studio, creating a space of playful pragmatism (if it works, it works!), and the welcoming warmth of a light among dramatic shadows.

Be sure to visit Leave a Light On: The 26th Annual Juried Woodworking Exhibition on display in our Visitor Center now through December 29, 2019.

You can also learn more about Wharton Esherick’s World’s Fair Exhibit, “A Pennsylvania Hill House” in our previous post: Wharton at the World’s Fair

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

October 2019