Left: Library Ladder, Wharton Esherick, 1969, walnut. Photo by Eoin O’Neill. Right: Doris, Wharton Esherick, 1920, plaster.

In the publication Wharton Esherick Studio & Collection, former WEM Curator Paul Eisenhauer draws a connection from Esherick’s iconic Library Ladder back to Doris, a small plaster sculpture. Eisenhauer describes Doris as Esherick’s “1920 Steiner-influenced sculpture, a dancer, her gown spiraling about her, one arm bent at the waist, the other raised to the sky with fingers pulling the power of heaven to Earth.” The subject of this small study, the dancer Doris Canfield, is in a spiraling pose born out of eurythmy, the expressive dance form based on the philosophies of Rudolph Steiner. Though made some forty years apart, Library Ladder and Doris share an essential gesture that was critical to Steiner’s philosophy — the spiral or twist — that highlights the relationship between the figure and Esherick’s furniture.

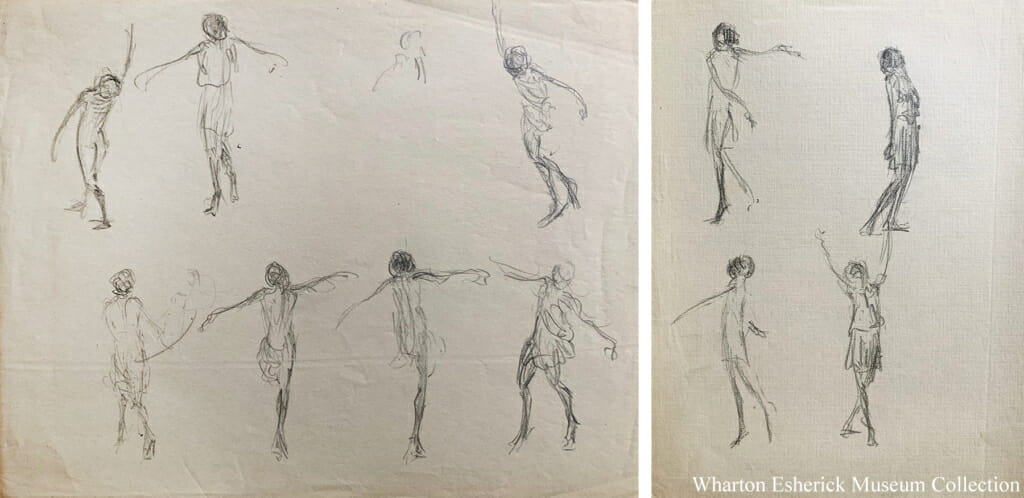

As a regular visitor to the Gardner Doing Dance Camp, Esherick observed dancers like Canfield exploring eurythmy, Rhythmic dance, and other modern dance forms. His wife Letty also danced, sometimes holding classes at their home in Paoli. At times, Esherick joined in with the dance. Otherwise, he was sketching away, attempting to capture bodies in motion. Esherick always loved to draw; according to his mother, he would fill up any spare scrap of paper in the house. With degrees in Painting and Drawing from the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts) and the Pennsylvania School of the Fine Arts, figure study was prominent in Esherick’s artistic training. The desire to draw the human body never left him, even when his ambitions turned to furniture and functional forms.

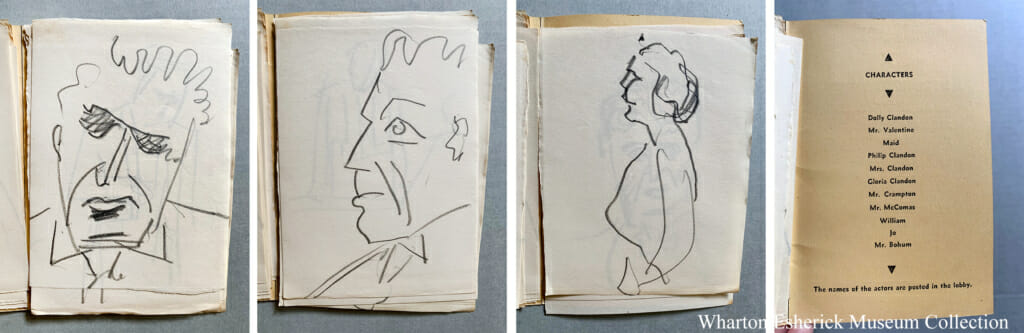

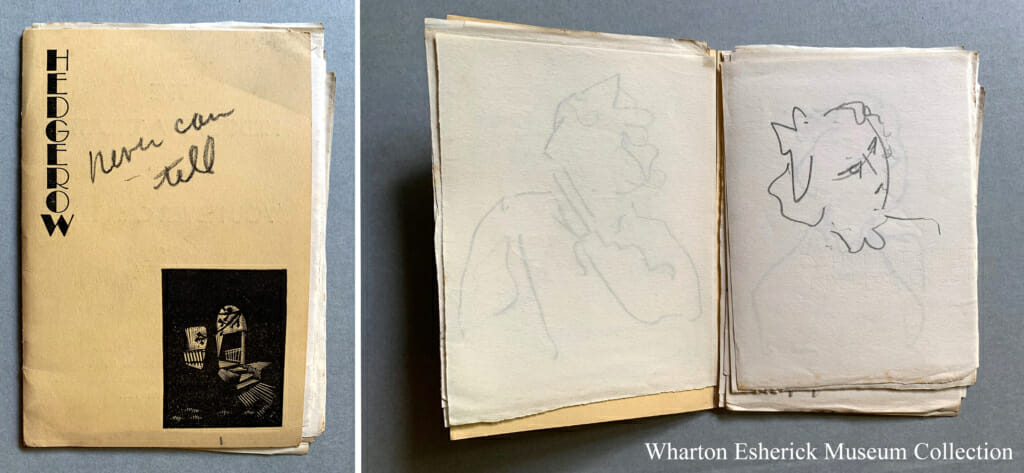

The Museum’s collection contains thousands of drawings. While some of these are plans for furniture and others capture the landscape, the majority of these pages are filled with figures. Casual sketches capture a friend asleep on the beach or settled in a chair, giving time for a more detailed drawing, but many pages fill up with glimpses of figures in motion. About half the museum’s works on paper collection are drawings from the Hedgerow Theatre, where Esherick would draw the actors and sets during rehearsals and performances, sometimes on the program booklets themselves. Esherick would capture actors in motion with just a few essential marks. In confident, skilled drawings filled with Esherick’s trademark sense of humor and big personality, we see both full figures and portraits depicting the characters he saw on stage.

Esherick’s Hedgerow Theatre program for the George Bernard Shaw play “You Never Can Tell,” filled with loose pencil drawings. Approx 4″ x 5.5″. The program cover features a woodcut by Esherick depicting the theater’s front entrance.

Esherick’s regular sketching of the figure is rare for furniture designers. This drawing practice likely had a significant impact on the forms he created, continually honing his abilities with line weight and quality, proportion, and paring down form to a few sparse marks.

A figure drawing class is centered around making quick, gestural sketches:

Draw a figure in 10 minutes.

Draw a figure in 5 minutes.

Draw a figure in 1 minute.

Draw a figure in 10 seconds.

“Delores Turns In,” pencil drawing by Wharton Esherick made during a trip to Barnegat Bay, New Jersey.

As you might imagine, the goal of a 10-second gesture drawing is to get down to the essence of the pose. The curve of the spine, tilt of the hips, a firmly planted leg, distilled in a single line. While not all of Esherick’s drawings remained so unfinished, each manages to capture something essential about physicality. In Esherick’s woodwork, we see those honed drawing skills return within the curves of the furniture itself.

Speaking at an Annual Party gathering at the Museum, composer George Rochberg described Esherick’s furniture as “classical,” moving away from objects disguised by decoration to essential, universal forms. Esherick’s interest in getting to the root of what makes something transcendent — a chair or a body — brings the artist’s life drawing and furniture practices perfectly in sync with one another.

Post written by Communications & Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

August 2020