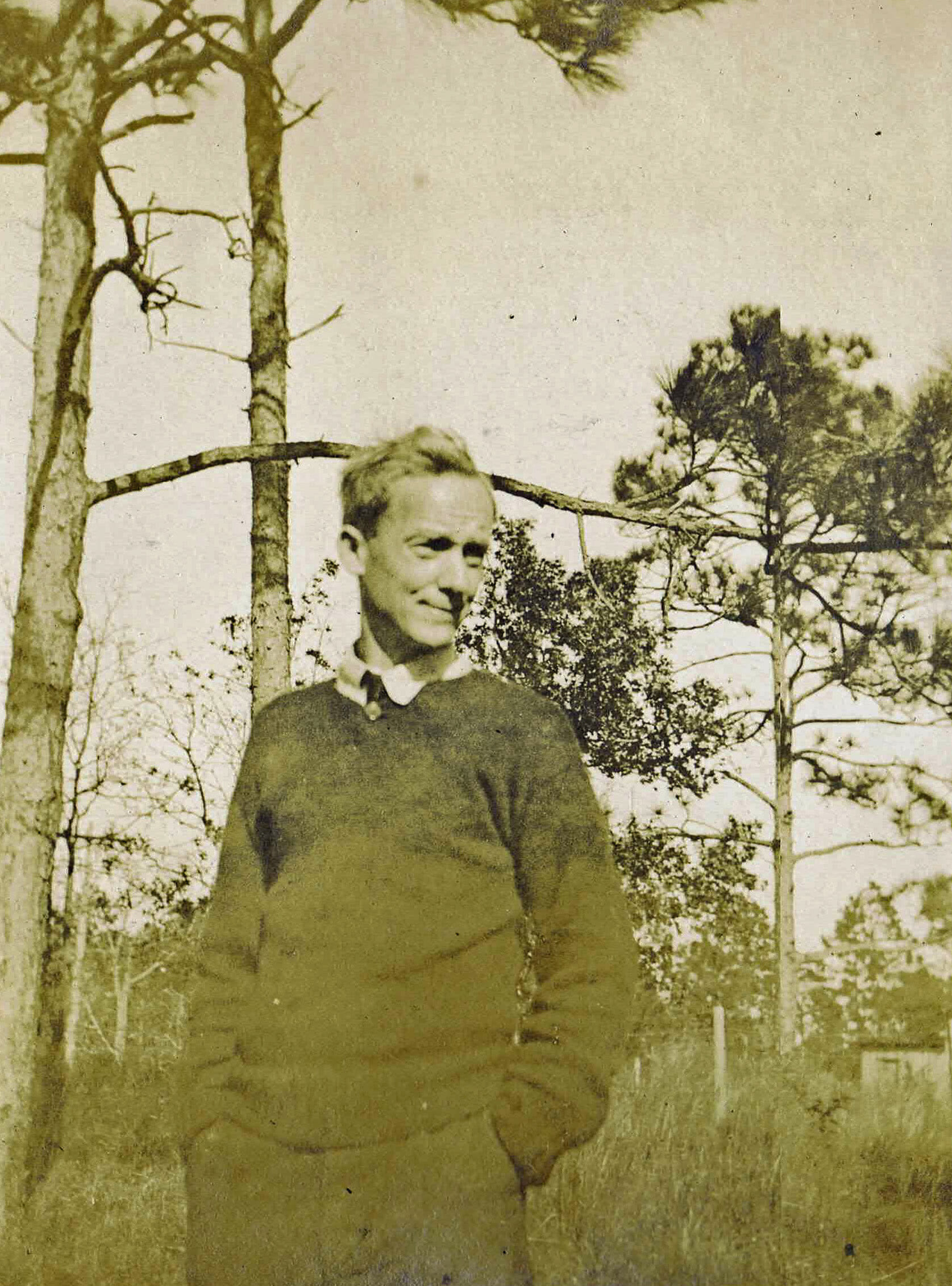

Wharton Esherick in Fairhope, 1919. Esherick Family Photo Albums

Fairhope, Alabama sits high upon the bluffs overlooking Mobile Bay – or as the first Spanish explorers called it: la Bahia de Spirito Sancto or “the Bay of the Holy Spirit” for its breathtaking views and peaceful serenity. Fairhope has a long history of attracting artists, writers, and craftspeople going back to its founding as a single tax colony in 1894. It was Letty Esherick’s interest in progressive education that brought the Eshericks to Fairhope for their first visit in 1919; drawn by Marietta Johnson and her School for Organic Education. Fairhope proved to be a life-changing experience for Esherick, who was struggling to find his artistic voice at the time of their trip. It was in Fairhope that Esherick picked up his first set of woodcarving tools and explored a new medium that would lead to his artistic legacy.

A Fair Hope of Success

The idea of Fairhope emerged in Des Moines, Iowa in the 1890s when a group of Henry George admirers began meeting to discuss his principles of a single tax community. The group’s leader Ernest B. Gaston felt that George’s philosophy deserved the chance to be tested. George’s plan proposed a community where only the land was taxed, which he believed, and Gaston agreed, would stimulate economic growth. Gaston was deeply upset with social conditions at the end of the 19th century and saw the single tax theory as a way to even the playing field.

Cottages in Fairhope

The group became the “Fairhope Industrial Association of Iowa,” deriving their name from a statement made that their experiment had a “fair hope of success.” In 1894 they established their colony and in 1904 they were officially incorporated. Membership to the colony cost $100 a year, and members were leased land on a 99-year renewable lease in which lessees would own whatever improvements made to the land including the construction of houses and other establishments. The colony’s “member’s only” model would only last four years.

By 1908, the Fairhope Industrial Association realized that in order to continue as a community, they had to open themselves up to non-members as lessees. As a result, the city of Fairhope was formed as a separate entity and formal municipality. Gaston had hoped that people who moved to the city of Fairhope would all choose to join the movement once they saw the benefits of the single tax community nearby, but they rarely did.

Letty

Letty had long been interested in the progressive education movement happening at the start of the 20th century and dreamed of opening her own school one day at the Esherick homestead, Sunekrest. She and Wharton attended a speaking engagement in Philadelphia that featured Marietta Johnson, a leader in the progressive education movement and founder of the Organic School in Fairhope. During Marietta’s speech, Letty hung on every word, and not long after she and Wharton decided to leave for Alabama where their 3-year-old daughter Mary could attend the Organic School, and Letty could volunteer and study under Marietta.

Today the Bell Building that stands on the original campus of the Organic School is now home to the Marietta Johnson Museum. Photo by WEM docent Bob Zrebeic.

Marietta Johnson’s educational philosophy hearkened back to the days before public schools, believing education should be as organic as children learning from their surroundings through experience. The curriculum at the Organic School incorporated traditional academic studies with handcrafts, music, singing, folk dancing and wholesome play in the fresh air. Marietta believed that arts were natural and elemental to children and that knowledge of practical arts, such as woodworking and pottery, might actually help children later in life as they’d need to provide for themselves. Over the course of the Esherick’s two visits, all three of the Esherick children attended The Organic School.

Wharton

While Wharton spent much of his time in Fairhope traversing the countryside sketching and painting, he also found himself involved at the Organic School. When he voiced criticism of how art was being taught at the school, Marietta challenged him by asking what he was going to do about it – so he became an art teacher. He chose to teach in the afternoons, so he could save the best part of the day, the morning, for himself. He also met author Sherwood Anderson, best known for his work Winesburg, Ohio, and the two formed a friendship that would last through Anderson’s death in 1941.

Though Fairhope was a progressive community, segregation still affected Fairhope’s African American population. Esherick and Anderson were both highly interested in the African American culture and often attended services at their church. Not long after he started teaching at the Organic School, Esherick also became an art teacher at the black school, which the white residents of Fairhope did not like. A lawyer warned Wharton about what the townspeople would do:

“‘Mr. Esherick,’ he says, ‘You’re going to be chased out of town.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘The people are very much disturbed at you. They know you’re going out and teaching at that colored school and they don’t like it. … When you’re away they will come here and they’ll gather all the things in your house and put them on the wharf there and kick you out of town.”

Esherick ignored the lawyer’s warning and instead chose to walk two miles out of his way so that the locals would not know he was headed to the black community. At the end of the school year, Esherick held an exhibition of his paintings at the Organic School and invited his students from the black school to attend and see their instructor’s work. This caused a major uproar in Fairhope, but Marietta stood by Esherick and allowed everyone to enjoy his paintings which featured the beautiful carved wooden frames he had made at the Organic School.

The Painter Becomes a Printer and a Sculptor

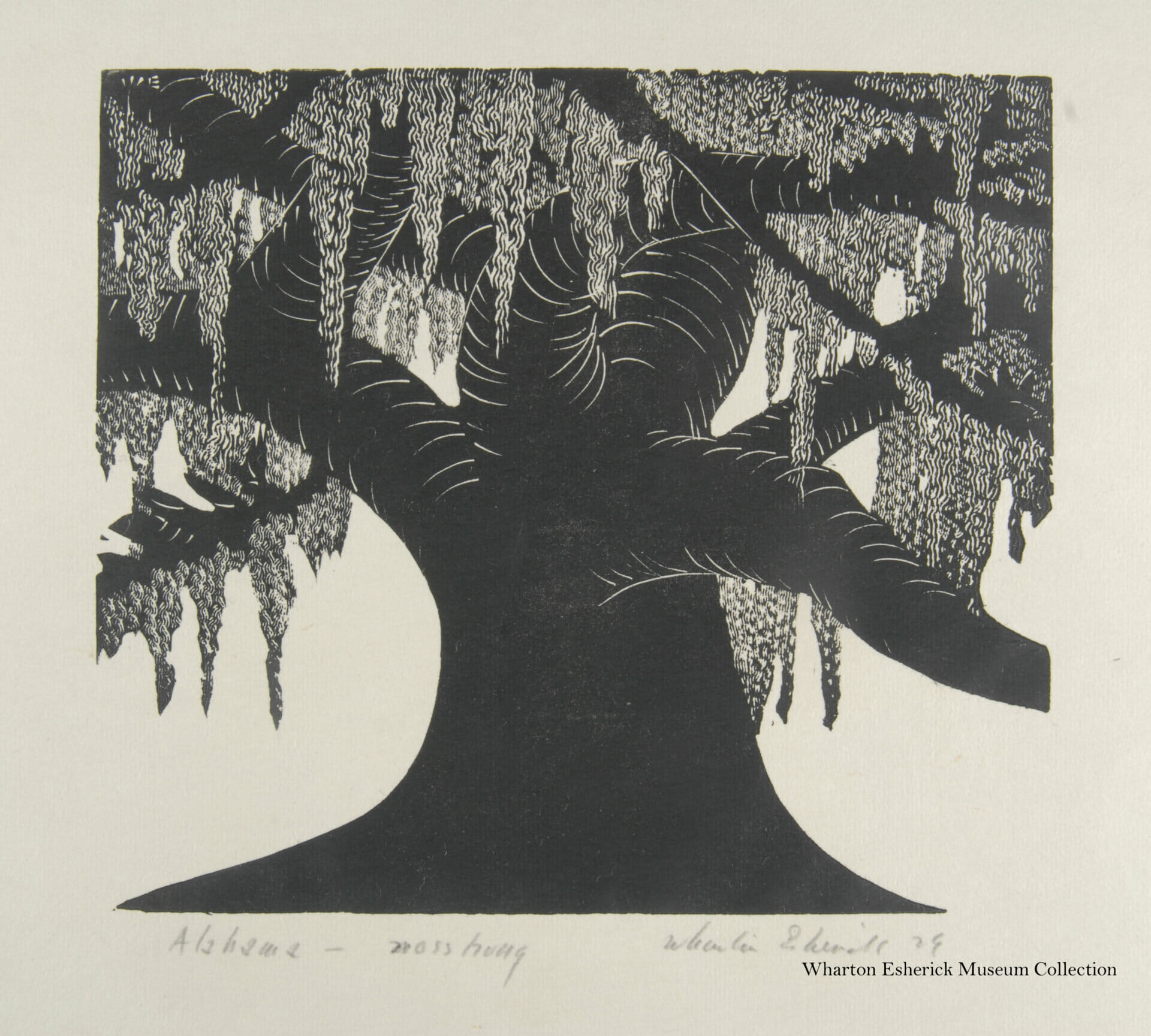

Alabama – Moss Hung, 1929 Woodcut by Wharton Ehserick

It was Marietta Johnson who suggested Wharton explore woodcarving while he was at the Organic School. To compliment his oil paintings, he carved elaborate wooden frames which often reflected the subject of the painting within. The frames were a big hit and Wharton discovered a medium which he greatly enjoyed.

He began exploring printmaking, turning many of his sketches of Fairhope’s trees into block prints like the ones seen here. In Fairhope, he met author Mary Marcy, who asked him to illustrate a book of poetry she was writing. He chose to do so with woodcuts. Marcy would send Esherick one of her poems, he’d carve the block and send her a print and they continued back and forth until the book was finished. Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk was published in 1922 featuring 78 of the 100 woodblocks Esherick created for the publication.

During the Esherick’s second visit in 1929-1930, Esherick met potter Peter McAdam. McAdam worked at O’Neal Pottery in nearby Daphne and became known throughout southern Alabama for his creative ceramic work – especially his face jugs, monkey jugs and other ceramic novelties. He is noted as being the most artistic of all the potters in the area and while others made purely utilitarian pieces, McAdam’s work always had great artistic flair. It’s easy to see why he and Esherick got on well. It was at O’Neal Pottery that Esherick and McAdam made a series of ceramic animals which Esherick brought back to Paoli to install as yard ornaments or sell to clients. The two also created several dishes for the Esherick family including redware dinner plates with a pelican carved into the surface, and several colorful bowls and dessert plates.

Dishes by Esherick & McAdam

More on Fairhope

Want to learn more about Fairhope? Fairhope Days, an exhibit that takes a close look at the Esherick’s time in Fairhope and features some rarely seen artifacts from their time there is on display in the Museum’s Visitor Center gallery through September 2nd. Highlights of the show include a handmade travel chess set Esherick made at the Organic School, a Fairhope-era oil painting in an elaborately carved frame Esherick crafted there, as well as two ceramic animals – an elephant and a pelican – made by Esherick and McAdam at his pottery in Daphne.

On July 8, the Museum will host wood artist and Esherick scholar Mark Sfirri for an Exhibit Talk at 2pm! Mark has been studying and researching Wharton Esherick since 2006 and has since authored six articles on Esherick and his work. In conjunction with our summer exhibit Fairhope Days, Mark will discuss Fairhope’s founding and history as well as Marietta Johnson and her School for Organic Education, the impetus for the Esherick’s initial journey south. Admission to the Exhibit Talk is free, admission for a self-guided tour of the Studio, open from 1 to 4 p.m., is $12 for adults and $6 for children ages 5-12.

Post written by Curator & Program Director, Laura Heemer.