Throughout his lifetime, Wharton Esherick created several self portraits. Inside the Studio, visitors can see one such painting done in 1919 during Esherick’s early years as an artist. The image, which features Esherick looking directly at the viewer and wearing a traditional artist’s smock, was completed in an American Impressionist style that reflects Esherick’s training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (which he attended but did not graduate from) between 1908 and 1910. As Esherick’s sense of self – as a person and as an artist – changed and developed, he depicted himself differently as well. Upon entering the Studio, we see one such depiction in the form of a wooden coat peg mounted in the wall featuring Esherick overseeing the team that built the first iteration of his iconoclastic working space in 1926.

In addition to these more literal self portraits, Esherick’s personality, life, friends, family, humor, and overall sense of self emerge through his whole body of work, ranging from woodcut prints, furniture, and sculpture, to the interior and architecture of the Studio itself – and perhaps Esherick’s most notable and extensive self portrait is his Home and Studio writ large.

For our 28th Annual Juried Exhibition Home as Self, WEM invited artists to explore the meaning, creation, and form of self-portraiture. In this exhibition – which includes virtual and onsite components, as well as an accompanying catalog – we celebrate the work of 25 artists who have created pieces reflecting their own sense of what makes a self portrait.

Just as Esherick’s self portraits were diverse in form and approach, the artworks juried into Home as Self reflect a similarly expansive definition. The point of comparison doesn’t stop there, however. There are many interesting and exciting spaces in which the self-portraits made by these contemporary artists and Esherick’s own life come into conversation with one another.

Pato Hebert’s Detail Disoriented (Brain Fog), speaks to his challenges as a COVID long-hauler. After two years of illness he says, “I have difficulty with speech, processing and retaining information, and organizing and managing details.” Hebert created a spoon with a hole in the bowl that embodies this sense of his new understanding of self, personal struggle, and what is lost post diagnosis. His choice of format may reflect that across many contexts, spoons often represent sustenance and support; for example, we think of the person with a “silver spoon” as someone who is fully resourced while “spoon theory” is a metaphor used by many disabled or chronically ill folks to talk about their mental and physical energy and its limitations.

When considering Hebert’s piece alongside Esherick’s Spoon for Ruth, a rarely seen object here in the WEM collection, ideas of what sustains us are front and center. Esherick made this spoon for his 3 year old daughter and, like Hebert, he used a spoon as a stand-in form for a body, a person, and that person’s hope and need for care, nourishment, and overall health.

Wharton Esherick, Carved Three Legged Stool, 1931, Oak

Wharton Esherick, At Our Hearth, 1923, Woodcut print

Bronwen O’Wril’s Milking Stools came about during a time when she was learning anew about her roles as a daughter and a mother. She sees them as an expression of an archetypal parent-child relationship as well as a self portrait, saying “I am each stool and both of them at once.” O’Wril’s work not only shows how furniture can not only be understood via individual objects, but also in relation to context or other works of art.

O’Wril and Esherick’s works have both formal and conceptual similarities. Some of Esherick’s most iconic forms are his three-legged stools, each of which are highly unique while sharing a basic overall form. Pre-dating these classics, which he made from the 1950s onward, is Esherick’s Carved Three Legged Stool designed for his family home, Sunekrest (pronounced sun-e-krest). This stool was sited next to the family’s hearth, and, in its details, you can see a reflection of the home and family within. The lines that radiate across the seat of the stool might be thought of as a geometric rendering of rays of the sunlight. This image is not only depicted in the hammered copper hearth where the stool was located, it’s also reflected in the name of the home and the family to which it played host.

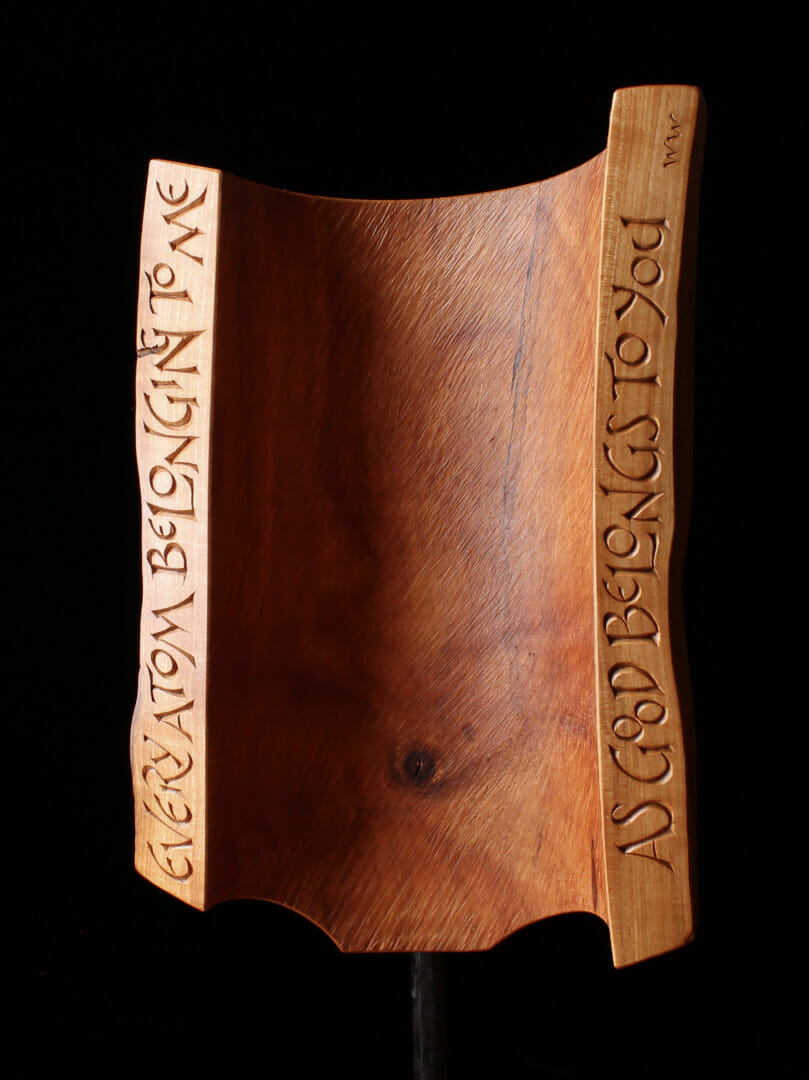

David Fisher’s Every Atom and much of Esherick’s work share a direct source of literary inspiration: the poetry of Walt Whitman. Fisher says about Every Atom that “The inspiration for this piece began when the bark pulled away from a crabapple log on our firewood stack and revealed the form of a human torso to my eye.” He goes on to express how the log’s lived-in surface reflects the artist’s sense of his own body. The written lines carved on the interior of his piece come from Whitman’s Song of Myself, a cri de coeur exploring the idea of the self, how we identify ourselves with others, and the relationship between self, nature, and the universe.

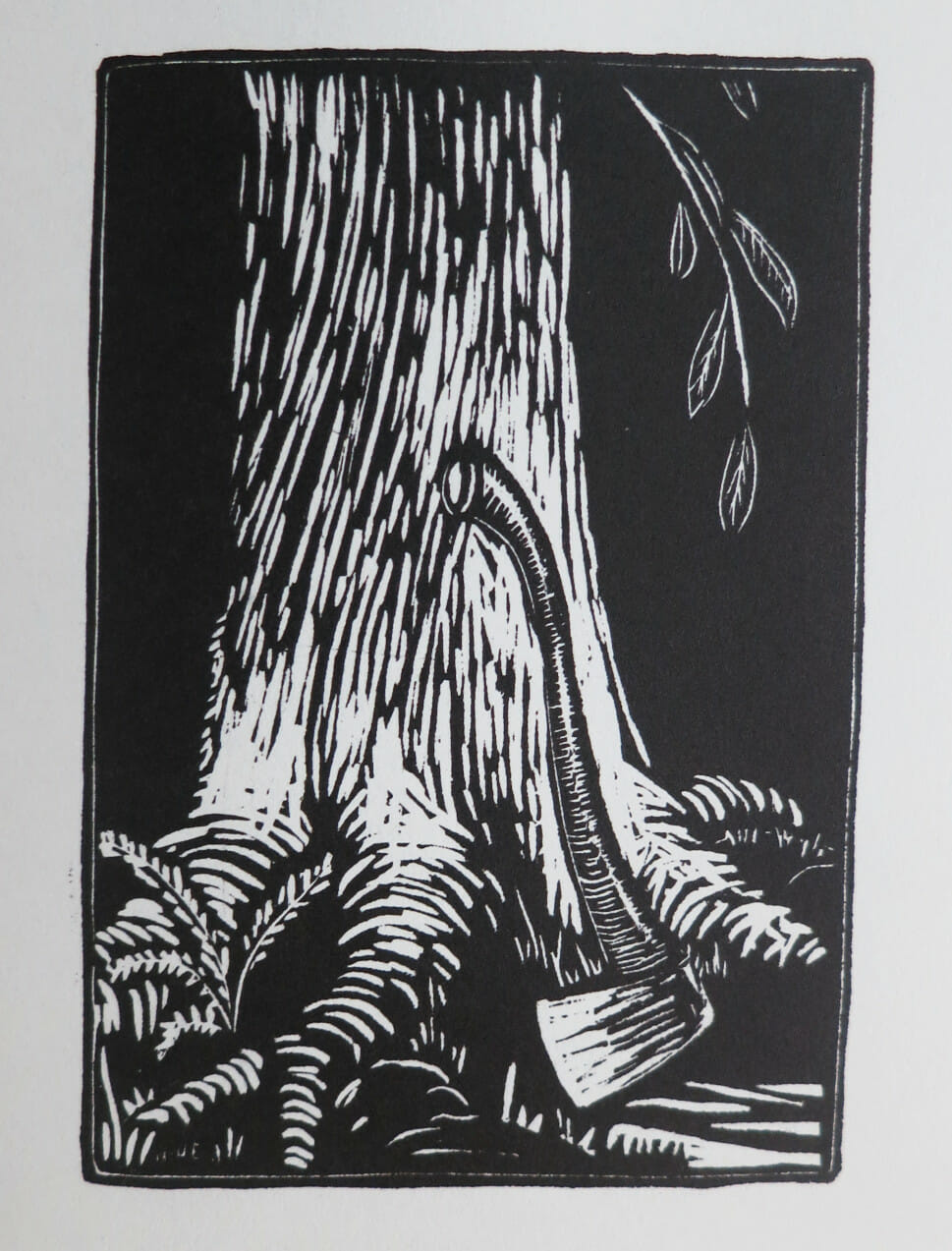

Like Fisher, Esherick also found inspiration and personal connection with Whitman’s understanding of what it means to construct a self . On the request of Harold Mason, owner of the Centaur Bookshop in Philadelphia, he created twelve woodcuts for Song of the Broad-Axe, Whitman’s symbolic musings on individuality and the nature of civilization. Esherick found Whitman’s themes of freedom from societal restraint and the power of both nature and craftsmen resonated with his own hopes for how his life’s direction would unfold. Formally, Every Atom reflects Esherick’s Frontispiece for his illustrated version of Whitman’s Song of the Broad-Axe, which depicts the solid, curved front of a tree ready to be shaped.

Explore all of the incredible works in the Home as Self virtual exhibition on our website through August 28th.

Join us for upcoming events in which we will talk with the prizewinning artists. The first of these events will be on July 12th with Katie Hudnall- Register on our website to attend!

Post written by Director of Curatorial Affairs and Strategic Partnerships, Emily Zilber, and Communications and Programs Specialist, Larissa Huff.

June 2022