The Whitney Biennial is thought of as a snapshot of art in America in the current moment, representing the most recent explorations by artists living and working in the country today. As the 2019 Whitney Biennial comes to a close, we here at the Wharton Esherick Museum began to think of this influential exhibition not only as it relates to the future of art, but as capturing distinct moments in our country’s cultural past.

Gertrude Vanderbuilt Whitney, circa 1920. Public domain, courtesy wikicommons.

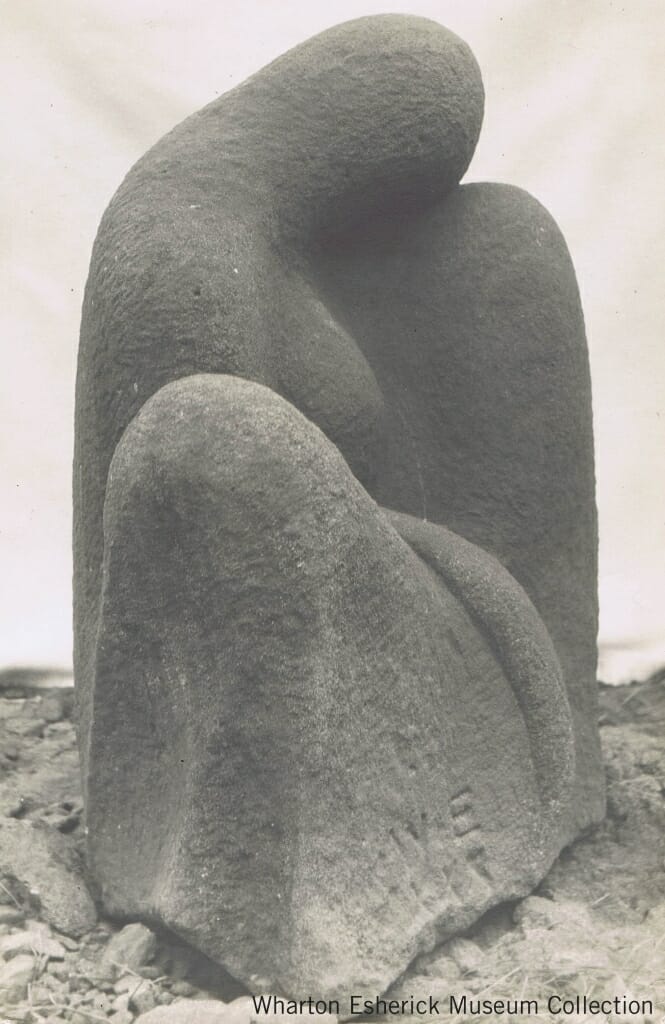

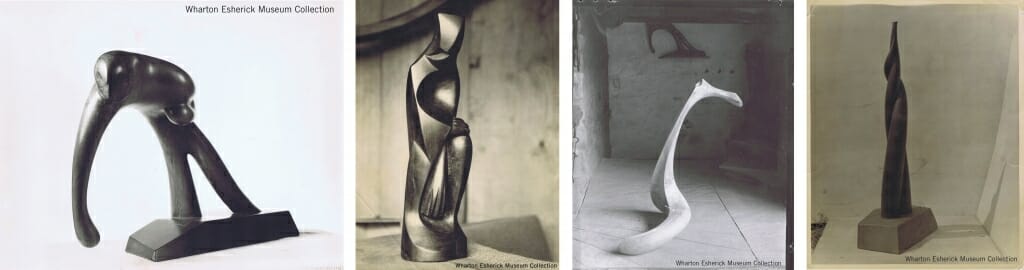

Founded in 1930 by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the Whitney Museum of American Art has a long history of hosting Annual and Biennial exhibitions to highlight the work of less established artists, and Wharton Esherick was among those supported by this mission early on. Esherick’s piece, Andante, a sandstone sculpture of a sitting figure carved during Esherick’s time in Fairhope, Alabama, was included in the First Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors and Prints which ran from December of 1933 to January 1934. Andante, which refers to a slow musical tempo, was so named not by Esherick himself, but by a blind musician (whom Esherick had befriended in Fairhope) as his hands felt the gentle curving form of the sculpture. Esherick’s work was selected again two years later for the Second Biennial Exhibition, which featured Oblivion, a sculpture well-known to our tour guests today.

Friends of Esherick were also represented in these early Whitney exhibitions, including Henry Varnum Poor and Julius Bloch. Other names in the catalogs would be even more familiar to your average art viewer today, like Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, or Grant Wood, while others seem forgotten to history. Esherick, Poor, and others in his circle were striving to find new, modern ways to depict the American experience, a task that must be tackled by every new generation of artists.

8-12 West 8th. St., the home of the Whitney Museum until 1954. Photo courtesy of Wikicommons and Beyond My Ken.

But we could turn the clock back even farther. Esherick’s involvement with the Whitney actually predates the museum itself. Prior to founding her museum, Gertrude Whitney, herself a sculptor (and a woman of great wealth), had established a studio in Greenwich Village. She recognized quickly the lack of exhibition space and opportunities for young artists at that time. New American art was largely snubbed in favor of European works or controlled to a stifling degree by academic organizations with little room for independent artists.

Mrs. Whitney’s interest in supporting American artists was met with ridicule in those early years, but fortunately, she was not dissuaded. With her long-time associate Julianna Force by her side, she established a gallery, the Whitney Studio, and by 1918 expanded to found the Whitney Studio Club. Juliana Force was named Director, later she would become the Founding Director of the Whitney Museum. With Juliana Force at the helm, the Club functioned as a lively social hub, with room for artistic debate and exploration. The space, located on West 4th St. in Greenwich Village, provided sketching and study areas, billiards, and gallery space. The Studio Club hosted solo and group exhibitions, often giving lesser-known artists their first opportunity for an exhibition. Esherick’s work was included in group exhibitions at the Studio Club as early as 1923, and again in 1926, 1928, and 1933. Eventually, the property expanded and became the original location of the Whitney Museum, with Mrs. Whitney’s substantial collection of American art on public view.

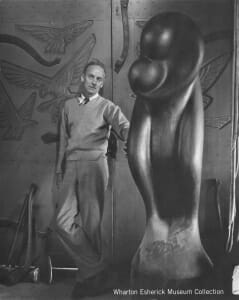

As the years went on and the museum administration changed hands, Wharton’s work continued to be on the radar of the Whitney’s curators. Esherick’s sculptural work was chosen for several invitational exhibitions (hosted annually in this period) between 1946 and 1954 with The Wallop, Sad Sack, Fun, and He and She (also known as The Pair) all going on display.

The Whitney’s collection includes three prints by Esherick (Of a Great City, April, and Winter Play) and one sculpture, Goslings, carved from American boxwood with a mahogany base. Years after it had been purchased, when a catalog of the Whitney collection was to be produced, Esherick gave the Museum this playful response to their request for a description of the work:

Watching the rhythm of goslings following each other across a road into a barnyard inspired the subject. The yellow color of boxwood in my shop “quacked” to me that my goslings were buried in that block, so I dug them out, and they paddled along after each other.

In typical Esherick fashion, he avoids speaking academically about his work, though the piece itself betrays his desire to pare down his subjects to their most essential gestures and rhythms. Happily, these goslings paddled out of the Whitney’s storage in 2015 for America is Hard to See, the inaugural exhibition in the Whitney’s new location in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, on display for new generations to enjoy. If you caught the recent Whitney Biennial, you may be struck by the immense changes in the last 100 years of art in America represented in these recurring exhibitions, though some of the essential gestures surely stick around.

Photo courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Wharton Esherick (1887-1970), Goslings, 1927. Boxwood on mahogany base, 13 7/8 × 20 1/4 × 3 3/4 in. (35.2 × 51.4 × 9.5 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase 33.43a-f

Check out these great links about the early history of the Whitney:

https://www.americanheritage.com/force-behind-whitney

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.