This May we kicked off an exciting new social media series, Creatives on Esherick, inviting contemporary artists, makers, and scholars to share their thoughts on Esherick and his enduring influence. Today we are delighted to share artist and woodworker Mark Sfirri’s reflections on Esherick, capturing the transformative influence Esherick had on his own creative path beginning with the seminal 1972 exhibition Woodenworks held at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery. To hear more responses on Esherick from contemporary creatives follow us on Facebook and Instagram and be sure to follow the hashtag #creativesonesherick.

Mark is a longtime supporter of the Wharton Esherick Museum and an avid Esherick scholar. He has lectured on Esherick across the country, authored or co-authored several articles on Esherick for Woodwork and Journal of Modern Craft, and served on the curatorial team of Wharton Esherick and the Birth of the American Modern, an exhibition and symposium at the University of Pennsylvania in 2010. As the head of the Fine Woodworking Program at Bucks County Community College for many years, Mark introduced countless students to Esherick’s work through inspiring visits to the Studio.

Most recently, Mark co-curated the Michener Art Museum’s upcoming exhibition Sculpture with a Purpose: Women, Patronage, and Wharton Esherick, 1930-45 in collaboration with Laura Turner Igoe, Curator of American Art at the Michener, scheduled to open this November.

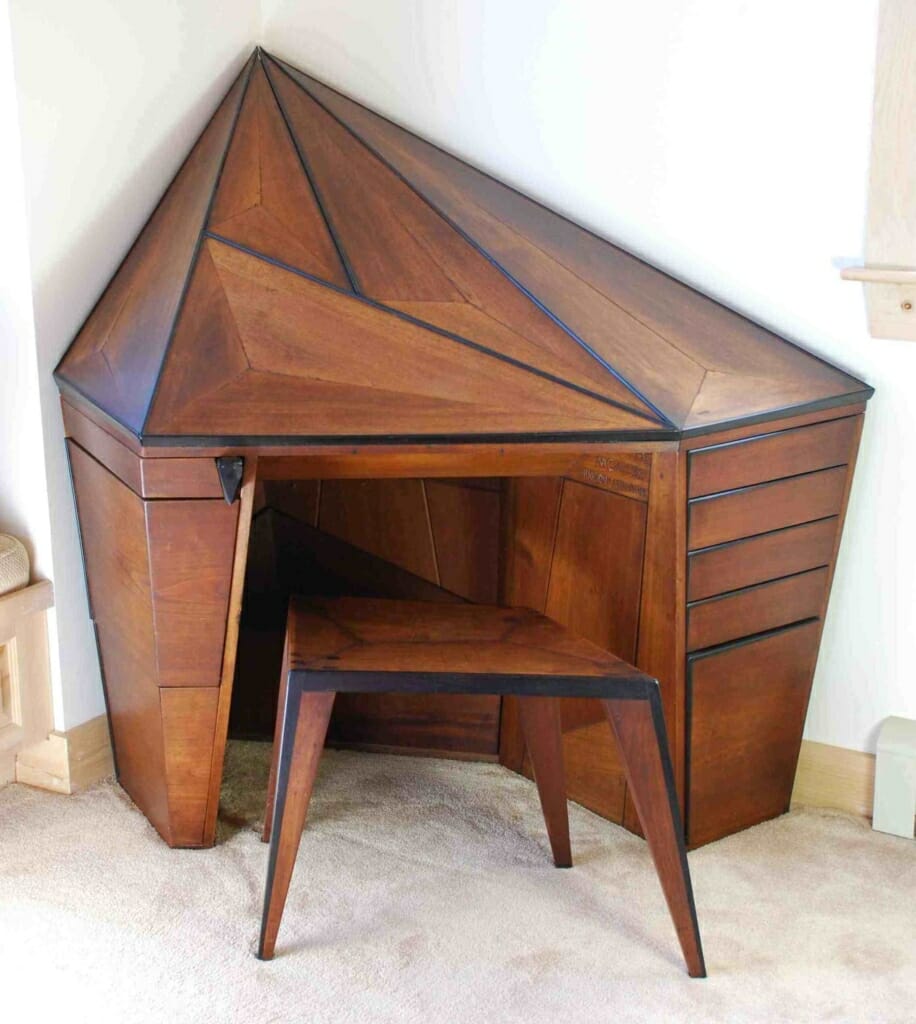

After I switched my major from Architecture to Furniture Design in 1972 at Rhode Island School of Design, I yearned to see examples of contemporary furniture. Unfortunately, there was very little to see in publications, let alone in person. The single publication I found was Objects USA. It was full of interesting pieces, but the section on wood was small and contained only a few examples by each maker. In a way, that lack of exposure was useful, because our work couldn’t be influenced by anything contemporary other than what was coming out of our own imaginations. (Now, of course, we’re exposed to thousands of images we can see at a moment’s notice.) Later that year the Renwick Gallery (a branch of the Smithsonian Art Museum) in Washington, D.C. mounted its inaugural exhibition, titled Woodenworks. It featured five of the most important woodworkers of the day: Sam Maloof, George Nakashima, Art Espenet Carpenter, Wendell Castle, and Wharton Esherick. Seeing that exhibition ranks as one of my top five art experiences. The variety and quality of work, all in one place, and at the beginning of my woodworking career, was transformative. One piece stood out above all of the rest, Wharton Esherick’s Corner Desk from 1931.

It was displayed with all three of its doors open so that you could view the partitions in the interior cascading down from one another, and dovetailed drawers in parallelograms coming out at different angles. I did try one drawer when no one was looking, which is unacceptable museum behavior, I know, but I had to do it. As I studied the desk, I came to realize that wood could become so many more things than I had thought possible. Woodworking construction didn’t need to be limited to rectangular shapes and square corners, and design didn’t need to be limited by symmetry.

I went back to college with a new perspective. Our first assignment was to make a dovetailed box with a drawer in it. I explained to my teacher, Tage Frid, that I wanted to make a box that was a parallelogram from the front and side view. His response was pretty quick. He told me that I needed to make one that was square first and after I’d accomplished that I could do whatever I wanted. That turned out to be good advice.

My first visit to the Esherick Museum was in 1974 or 1975. What an experience that was! Fortunately for me, I live about an hour away, so I’ve made several trips a year ever since then. There is always something new to see. When I ran the wood program at Bucks County Community College, I was the docent for my students every semester.

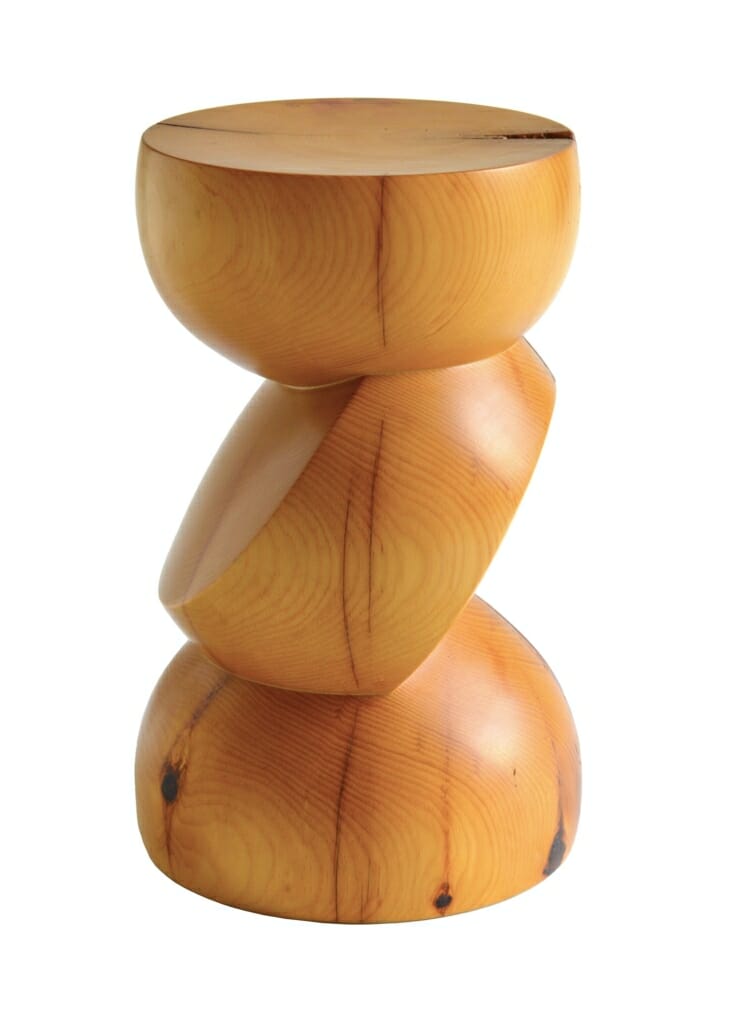

It was difficult to find examples of Esherick’s work outside of the Wharton Esherick Museum, so I was excited when, in 2006, a large collection was put up for auction at Rago Art and Auction Center in nearby Lambertville, New Jersey, including furniture, drawings, photographs, and other bits and pieces. I wrote an article about it for Woodwork magazine, titled “Esherick Emerges.” I discovered that the person who had consigned the work was the brother of the woman who owned Esherick’s Corner Desk, which led to an opportunity to see the desk again and to write about it, also for Woodwork, titled “Anatomy of a Masterpiece.” Esherick’s Corner Desk is not only my favorite Esherick piece; it’s simply my favorite piece of furniture. Some of his three-legged stools are right up there as well, because they’re so simple but so expressive, and his hammer-handle chairs would not be far behind.

Esherick was making furniture several decades before the four others in the Woodenworks exhibition had even begun their careers. The notion of individual personal expression in furniture in this country begins with Esherick in 1920. That makes 2020 the hundredth anniversary of studio furniture! I love how freely Esherick moved from furniture to sculpture, to printmaking, and how creative he was in each medium. His work was pioneering, diverse, and personal, and his example gave me the freedom to approach my own work in a similar fashion. In my opinion, all of us have been influenced by him either directly or by people who were influenced by him. It is an ongoing legacy.

You can learn more about Mark Sfirri, check out his work, and read his articles on Esherick at his website marksfirri.com

To hear more reflections on Esherick from contemporary artists, makers, and scholars follow us on Facebook and Instagram and be sure to follow the hashtag #creativesonesherick.

June 2020